Cry Sea, Cry Sky Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand

25 January – 24 February 2024

Here You Are, 9 March – 20 April 2024, Michael Lett Gallery, Auckland / Tamaki Makaurau, New Zealand

Cry Sea, Cry Sky Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand

25 January – 24 February 2024

Spotlight, Kunstmuseum St Gallen, Switzerland: 25 November 2023- 24 March 2024

Spotlight focuses on the individual artists for whom Kunstmuseum St Gallen holds significant bodies of work: John M. Armleder, Candice Breitz, Silvie Defraoui, Georg Gatsas, Sharon Hayes, Sara Masüger, Judy Millar, and Carl Ostendarp.

Against the Logic of War – Kyiv Biennial Augarten Contemporary, Vienna

17 October – 17 December 2023

Malerei – Galerie Mark Mueller, Zurich www.markmueller.ch

11 November – 23 December 2023

STAY ANOTHER DAY Nadene Milne Gallery, Christchurch, New Zealand

22 September – 20 October 2023

Judy Millar, Julia Morison, Séraphine Pick, Gretchen Albrecht

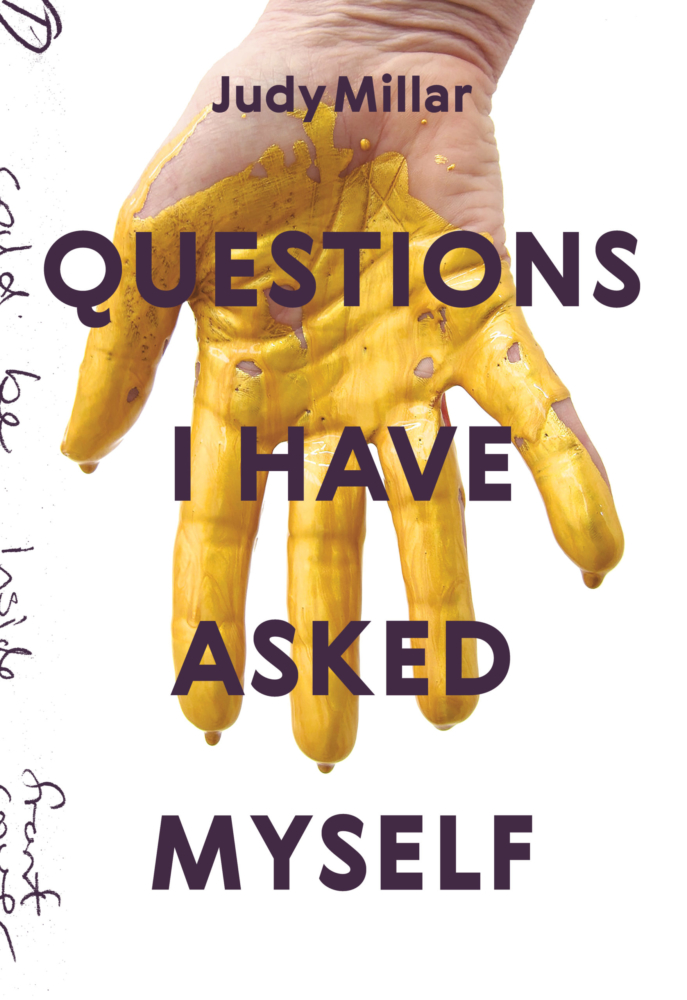

Questions I Have Asked Myself September 3 – November 15 2020

Galerie Mark Mueller, Zurich, Switzerland

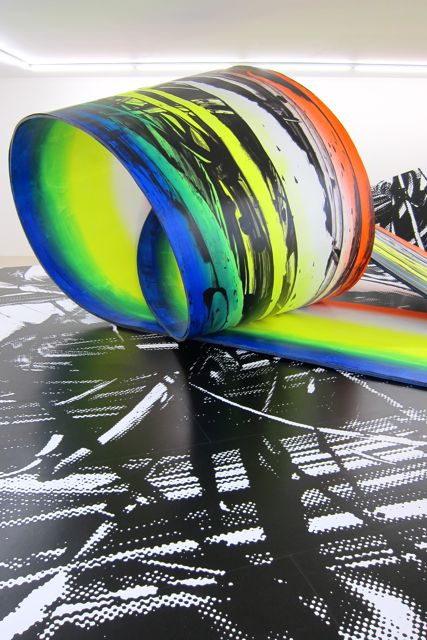

Double Hand 2020 acrylic on billboard vinyl 250 x 690cm included in Expanded Canvas – group exhibition Baroondara Town Hall Gallery, Melbourne, Australia 23 April – 2 July 2022

Whipped Up World. 27 January 2022 – 26 February 2022 Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand

New publication now available

Judy Millar: Questions I Have Asked Myself

ISBN 978-0-473-57646-2 179 pages

Available from http://www.pointpublishing.co.nz

City Gallery, Te Whare Toi, Wellington, Aotearoa

14 August–31 October 2021

Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

presents Clouds and Fire and Water and Air

4 August – 28 August 2021

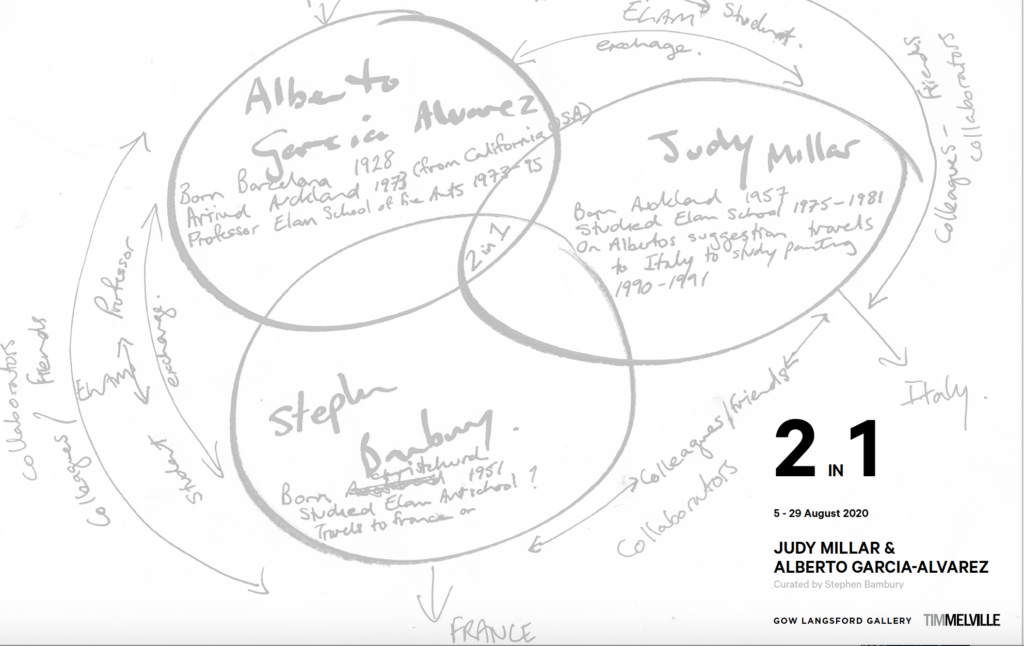

Gow Langsford Gallery and Tim Melville Gallery, Auckland, present 2 in 1: Judy Millar and Alberto Garcia Alvarez a two gallery exhibition curated by Stephen Bambury. 5 August – 29 August 2020. A catalogue will be published to accompany the exhibition.

Galerie Mark Mueller Zurich, Switzerland presents XXX die II on the 30th anniversary of the gallery 27 June – 15 August 2020

Robert Heald Gallery Wellington, New Zealand presents Paintovers – Opening 12 March 2020

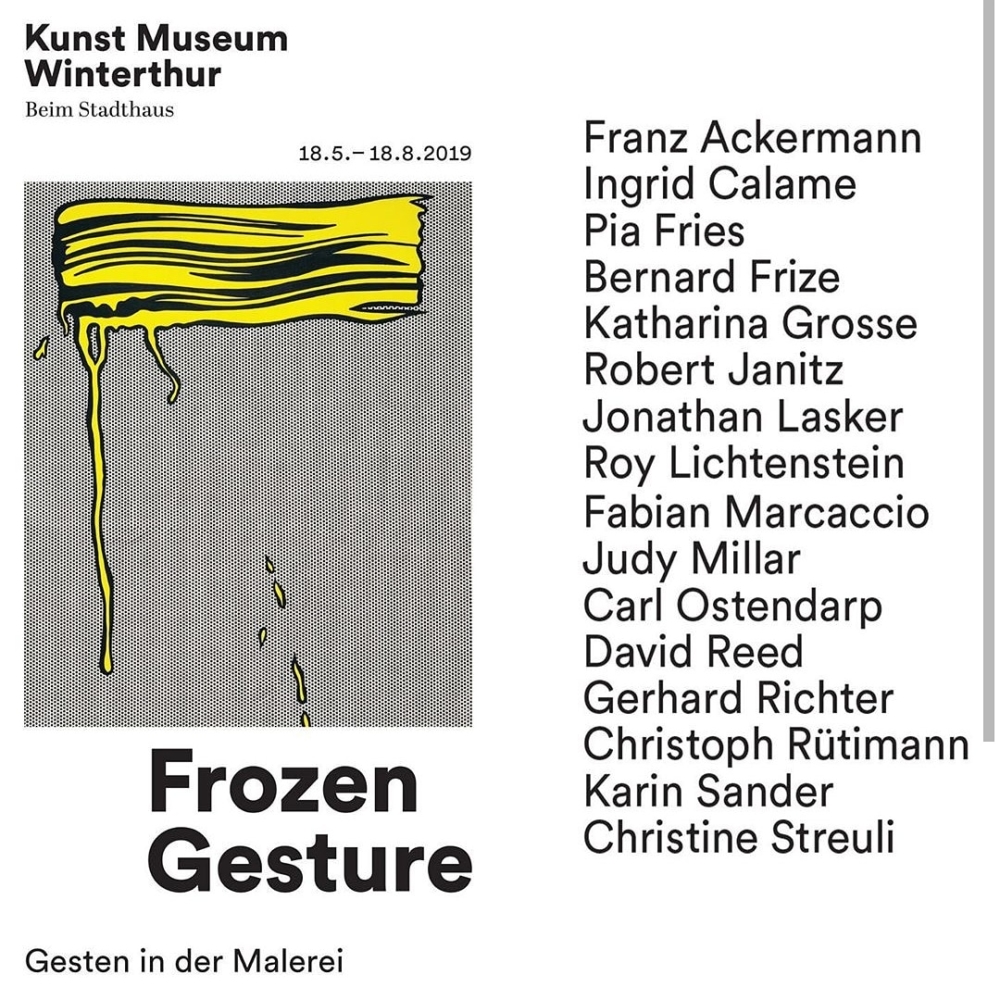

Frozen Gesture Kunst Museum Winterthur, Switzerland. 18th May – 18th August 2018

Galerie Mark Mueller, Zurich presents the group exhibition Single, but happy. 8th June – 20th July

Gow Langsford Gallery Auckland, New Zealand presents the group exhibition Enveloping Scales. 12 June – 6th July 2019

Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand presents A World Not Of Things, a solo exhibition of new paintings by Judy Millar. 17th April – 4th May 2019

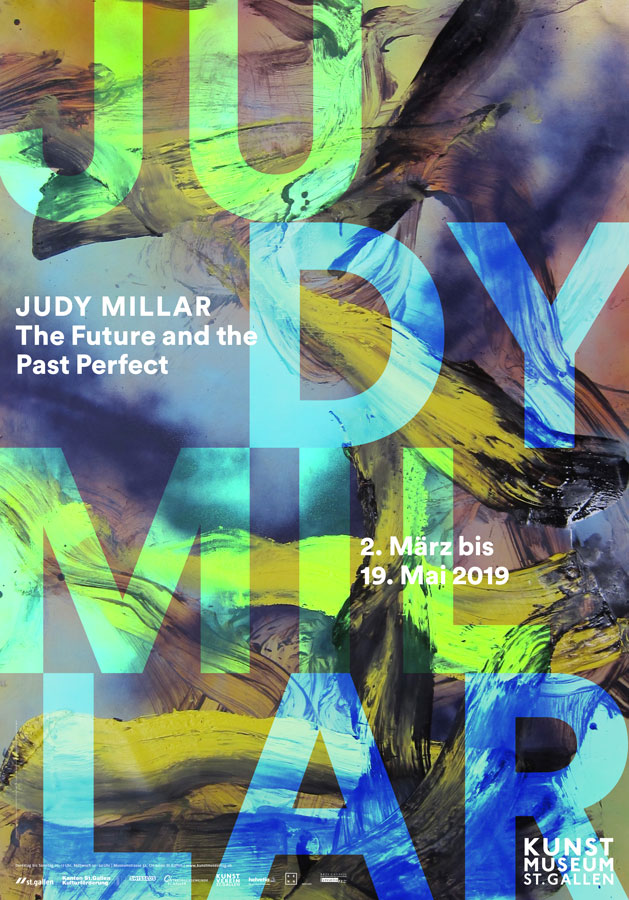

The Future and the Past Perfect – a survey of Millar’s work from 1981 to 2018. Kunstmuseum St Gallen, Switzerland. 2nd March – 19th May 2019.

Art Collector Australia interviews Judy Millar about her work in 2019’s Art Basel. Specifically in connection to the late New Zealand painter Colin McCahon’s legacy and his practice in relation to his International contemporaries.

In this new group of works form becomes the graph of activity. The appearance of “things” emerge from the web of painted lines and fields of colour. These things – hard to name but fleetingly apparent, establish a semi-believable pictorial space. These strangely spatial paintings exude an otherworldly luminosity as if emitting light from a distant time and place.

Bob Chaundy catches up with Judy Millar on the first evening of her first London Solo show.

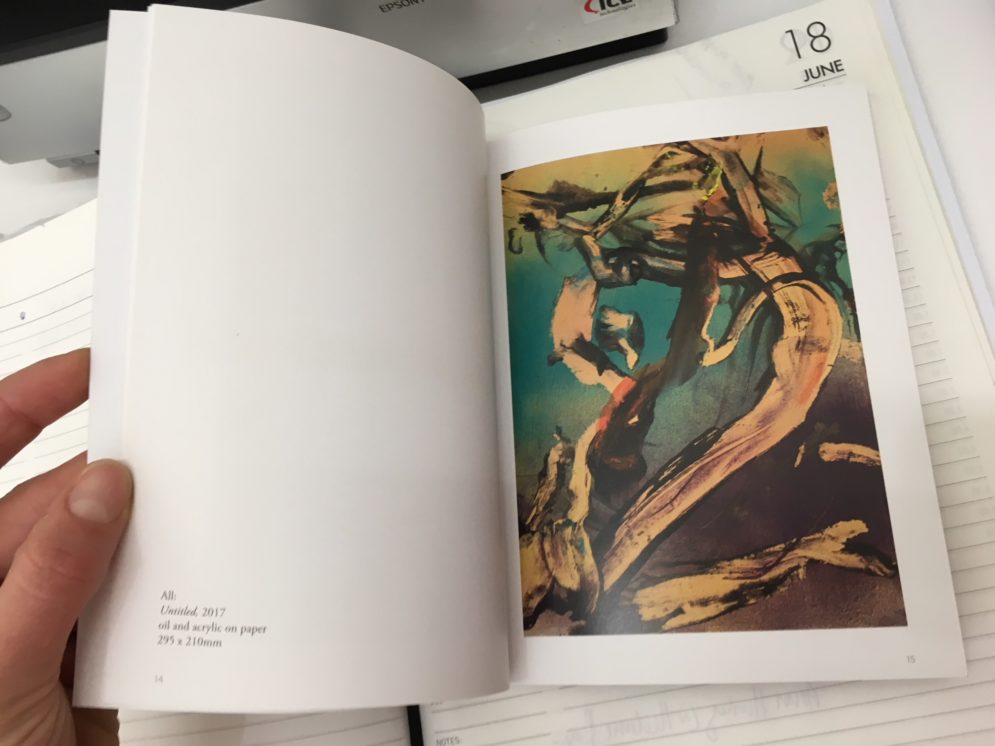

Most encounters with Millar’s paintings over the last decade have asked the viewer to step back a few paces to comprehend dramatic gesture at much larger than life size. These small studies invite a completely different mode of observation: up close and personal.

40 page catalogue published to coincide with the exhibition Studies in Place: Works on Paper 1989 & 2017 Gow Langsford Gallery ISBN: 978-0-9941276-2-4

Group Show at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. 9th September 2017 – August 2018.

A group exhibition curated by Kate Britton for Sullivan+Strumpf Sydney from 18th August 2018 – 15th September 2018.

Without our body we don’t exist, this to me is our experience of the world and this is what paintings can directly address.

Her work looks outwards rather than in, participating in a global conversation about the relationship that painting has with the real world.

If Millar ever ventures into a palette of silver, grey and faded rose, it would not shock me in the least.

Constant artistic experimentation and mystic inquisitiveness, engage and invigorate.

Her work not only activates space but also allows the kind of ‘space creation’ current in philosophy, cultural geography and advanced architectural research.

Solo show at Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington. Jan 25 – Feb 17, 2018.

Blood red, jade green, and a bruising purple resonate against yellow and incandescent orange in Judy Millar’s new paintings.

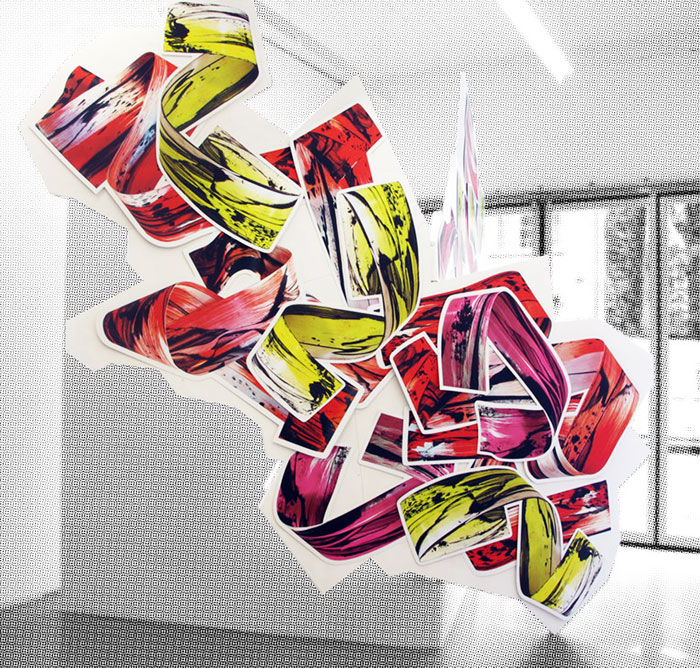

This work plays with the complexity of the vibrant junction between the Victorian, neo-Classical and 21st century architecture of the building.

Solo show at Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand. 2016.

I used to think painting was a way of thinking. Now I know it to be much more than that.

It is the flash of big brain meeting small brain, of consciousness meeting thought, or of consciousness meeting mind through the body.

Featuring Advancing All Electric – part of a group show at Galerie Mark Mueller. 2016

Group show at Frontviews Temporary, Kunstquartier Bethanien, Berlin. 2015.

Multi-media Installation at Te Uru Contemporary Gallery. 2015.

Press release for a solo exhibition at Galerie Mark Mueller. 2014.

An enchanting pop-up book full of Judy’s painted twists, twirls, swells and swirls.

A collaboration between Judy Millar and Paul Serville for the 2014 Servilles Winter campaign.

Cinema & Painting, Adam Art Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand.

11 February – 11 May 2014

This exhibition examined the intersection of these two screen-based arts against the backdrop of a culture characterized by the increasing plasticity of pictorial surfaces and flexibility of spaces of viewing.

Video of the construction of Space Work 7 commissioned for the exhibition Cinema and Painting, Adam Art Gallery, Wellington. 11 February – 11 May 2014

In response to Judy Millars Be Do Be Do Be Do Solo exhibition at the IMA Brisbane. 2013.

Do Be Do Solo exhibition at Hamish Morrison Galerie, Berlin, Germany 25th October – 16th November 2013. ...

Do Be Do Solo exhibition at Hamish Morrison Galerie, Berlin, Germany 25th October – 16th November ...

Solo exhibition at the Institute of Modern Art (IMA) Brisbane. 2013.

Solo exhibition at Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney, 2013.

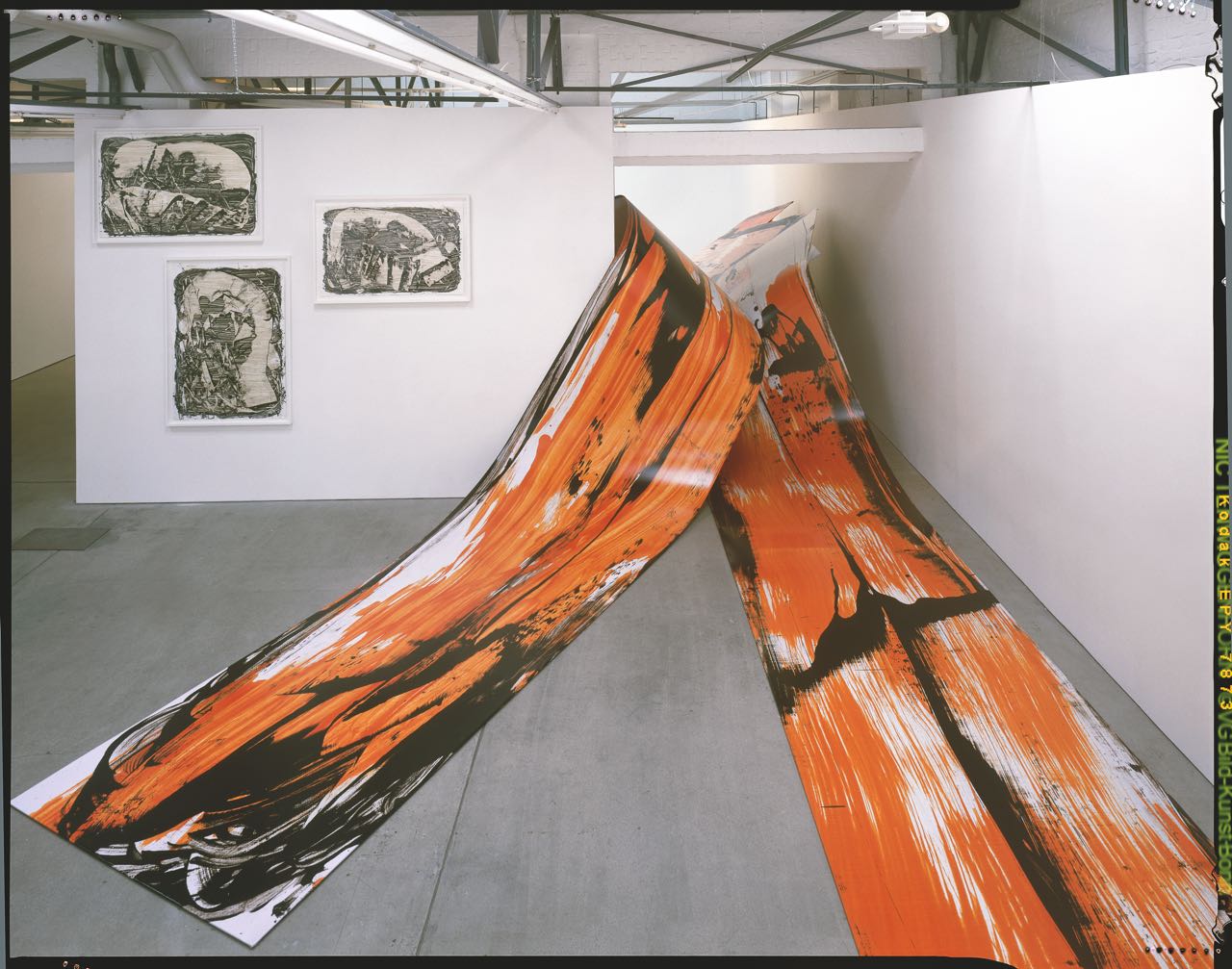

Exaggerated enlargements of handmade gestures with vivid colour.

“Contact” outlines a complex portrait of artistic production of the last forty years in Aoteaora/New Zealand.

This Collector´s Edition consists of 80 exemplars, each one comprising an original work.

Commanding brushstrokes of thin paint are wiped, erased and manipulated across the picture plane.

How do we distinguish between illusion and reality? How do we reconcile our physical and mental existence?

Robert Leonard talks to Judy Millar. The interview discusses her work in Personal Structures, Venice, 2010.

Solo exhibition Galerie Mark Mueller, Zurich, Switzerland

Judy Millar 08 Oct - 12 Nov 2011 A revealing aspect of abstract painting like that of Judy Millar is its minimum referential character. Colors, shapes, and movements cannot be decoded using a canon of signs taken from the world of things but function in a ...

Judy Millar 08 Oct - 12 Nov 2011 A revealing aspect of abstract painting like that of Judy Millar is its minimum referential ...

The Path of Luck Personal Structures, Palazzo Bembo, Venice, Italy 2 June 2011 – 27 November 2011 The Path of Luck 2011 wood, vinyl, paint dimensions variable ...

The Path of Luck Personal Structures, Palazzo Bembo, Venice, Italy 2 June 2011 – 27 November 2011 The Path of Luck 2011 wood, ...

Solo exhibition Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand 2011

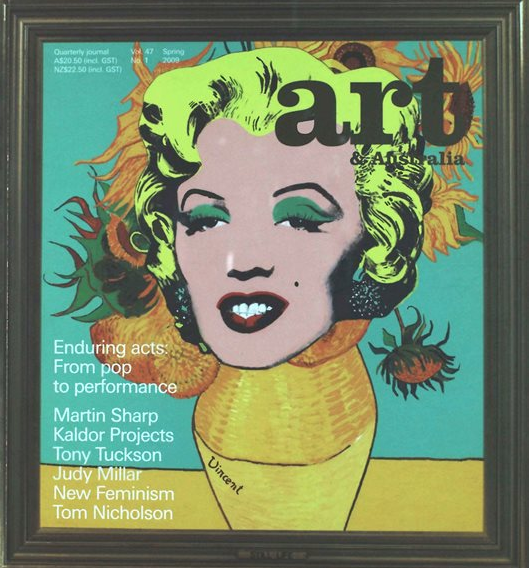

Essay by Morgan Thomas for Art and Australia. Vol 47. Spring. 2009.

Video collection of Giraffe-Bottle-Gun from the 53rd Venice Biennale.

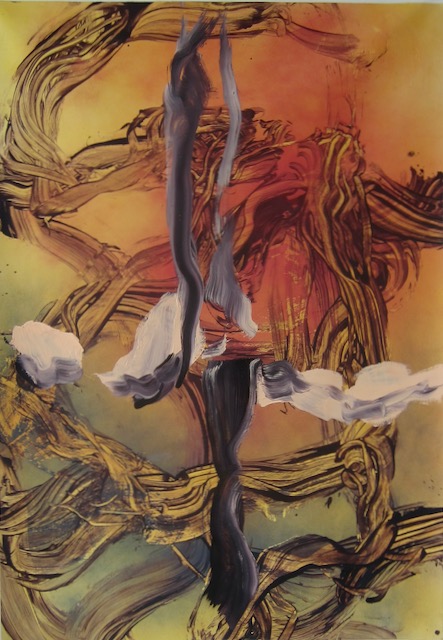

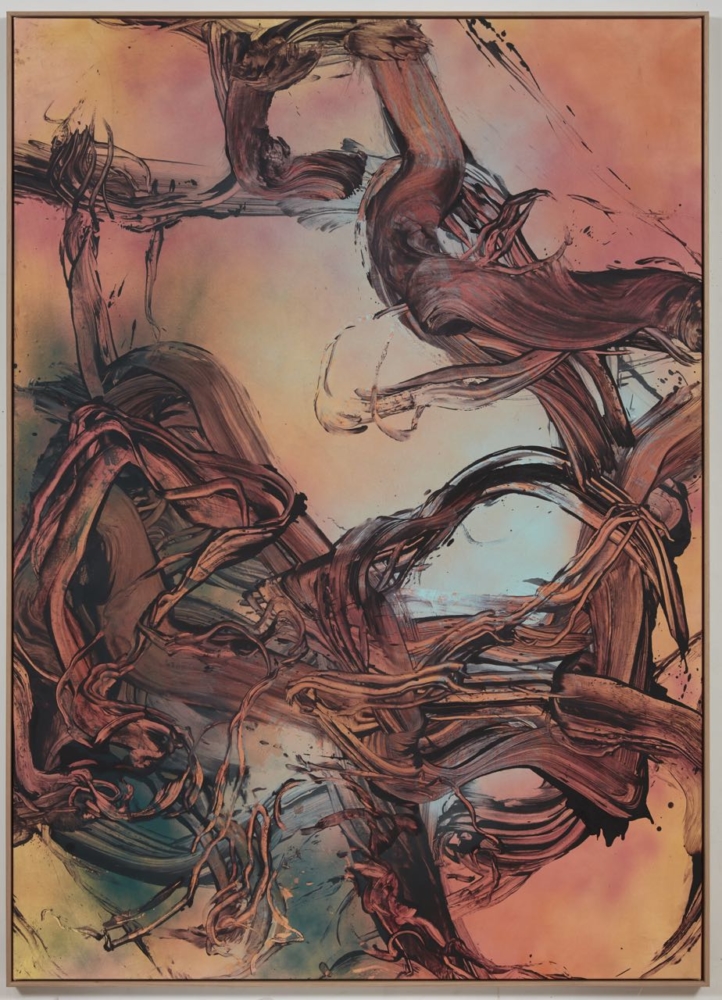

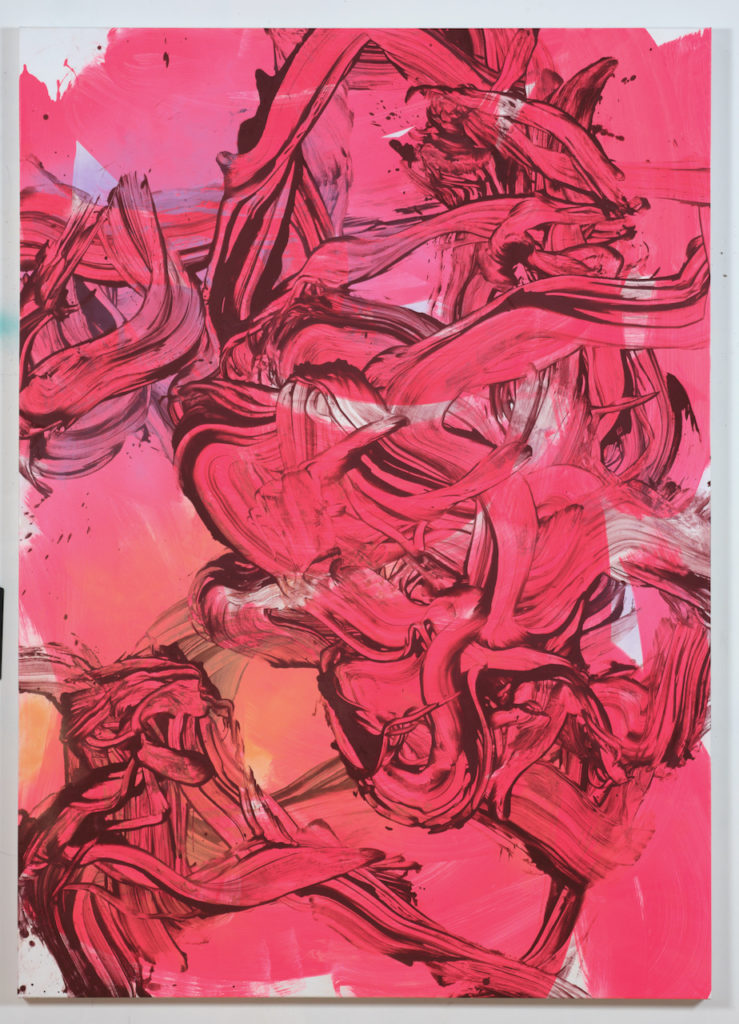

2017, 180 x 125 x 4 cm

Acrylic and oil on canvas

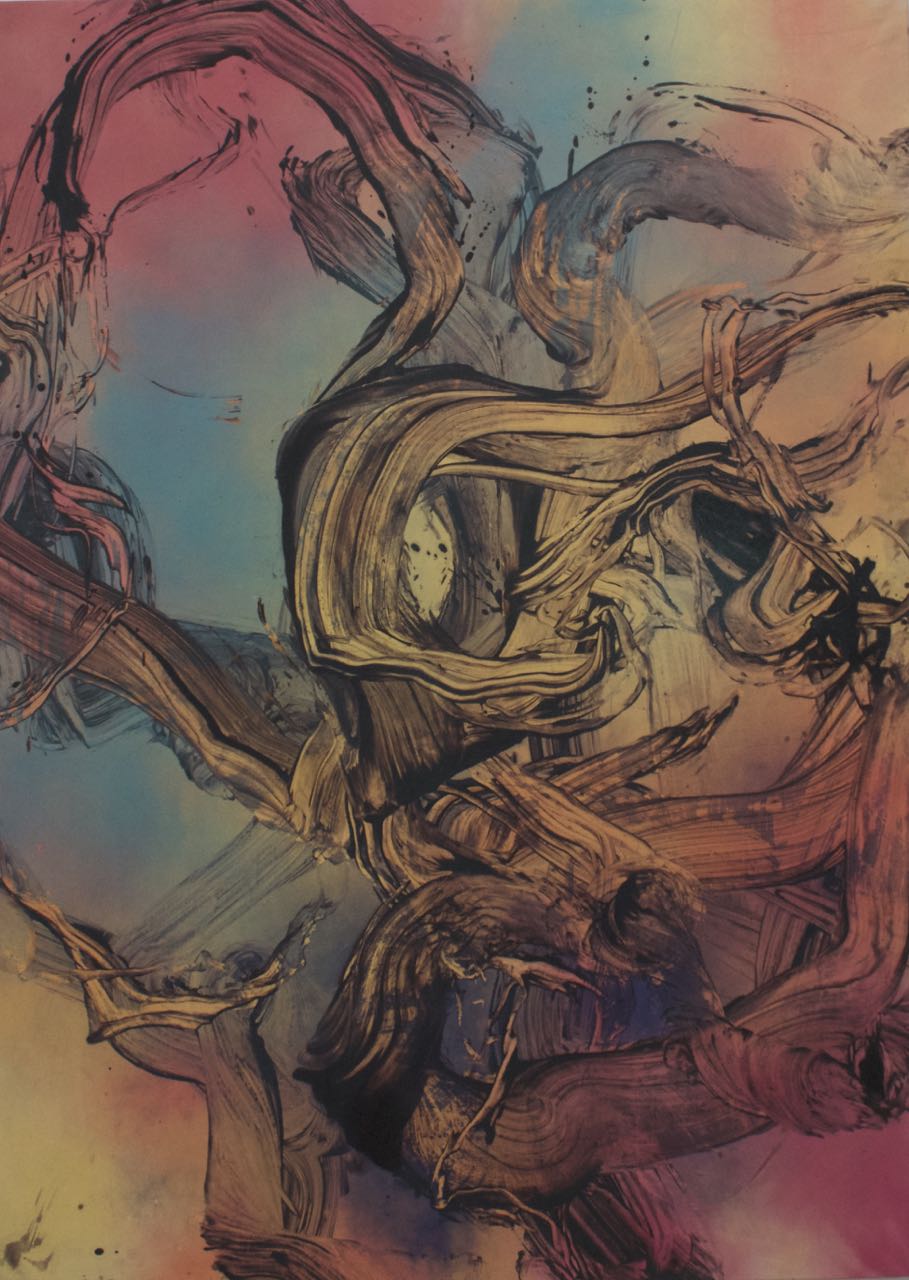

This large-scale work by New Zealand artist Judy Millar, created in 2017, is unsettling despite its abstract pictorial composition. The background surface, which appears gently blurred, deploys refracted, yet strong tones ranging from yellow to reddish, violet to turquoise. The foreground is formed by an amorphous structure that at first conjures up associations with twisted branches, roots or the dried remains of organic material. Abruptly changing direction, the bands of color, with sharply contrasting dark borders and varying widths that evoke echoes of an airbrush experiment gone deliberately awry, seem to float in a kind of psychedelic vacuum. The act of painting, which Millar sees as a constant attempt to turn away from the self, despite her massive, expressive, and singular gesture, is here frozen into a solitary, inanimate universe. Only the meandering object, oscillating like a conundrum between nature and artificial appearance, unmasked by the artist as »Hollow Bones« in the title, hints at traces of former life. But this has long since been extinguished. (Susanne Jäger)

STAY ANOTHER DAY Nadene Milne Gallery, Christchurch, New Zealand

22 September – 20 October 2023

Stay Another Day brings together four artists to celebrate decades of art making and a long-term commitment to a creative life and practice. Collectively their practices speak of the resilience, courage and discipline which form the foundations of a life’s work.

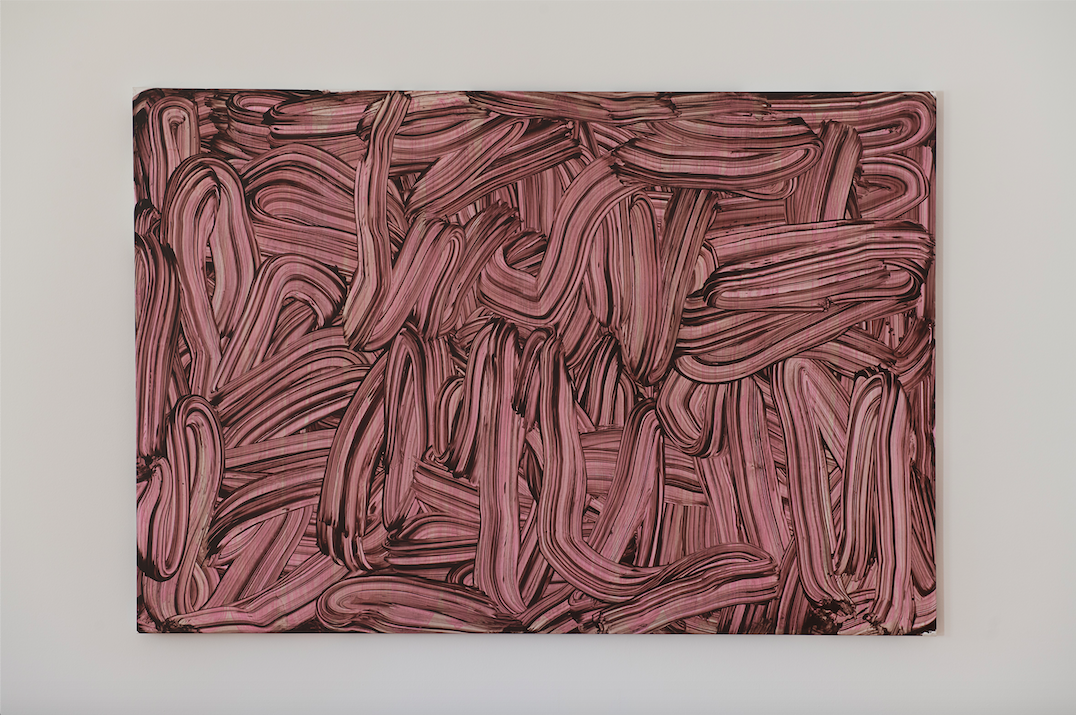

All Now 2023 acrylic oil on canvas 210x80cm

Judy Millar

«Questions I have asked myself»

the visual limits

of now you see it

now you don’t

where is the edge of vision?[i]

In hardly any other field than the arts are our (human) limits of perception, consciousness, and comprehension so ceaselessly explored and challenged. It is the artistic search for those very liminal experiences which are able to transport us to different, previously unknown places — places of the in-between, places of the other, places of the “unthinkable”. Ultimately, artists seem to have always been driven by a desire to expand our horizons and “bring together things outside of normal classifications, and glean from these affinities a new kind of knowledge which opens our eyes to certain unperceived aspects of our world and to the unconscious of our vision.”[ii] In some cases, the artistic quest to find these places becomes a crucial part of the approach and of the work itself. They create specific spaces and places based on our shared reality, yet challenging and expanding it at the same time: simultaneously real and unreal spaces, spaces that overturn or transform the everyday – or in other words: heterotopias. The French philosopher and writer Michel Foucault outlines the notion of heterotopia to describe certain cultural, institutional and discursive spaces.[iii] According to Foucault, heterotopias can be “real places — places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society — which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted.”[iv] They are places and spaces that are in different ways separate worlds within our world, mirroring and yet distinguishing themselves from what is outside. What characterizes them is a separation from and a tension with the remaining quotidian space, but in the sense of correlations or resemblances. From this point of view, the work of Judy Millar is as much a heterotopic microcosm as it is a painterly counter-site. At Galerie Mark Müller, the New Zealand painter takes us to various intangible site of escape, containment, rest, pleasure and transformation by exploring our edge of vision.

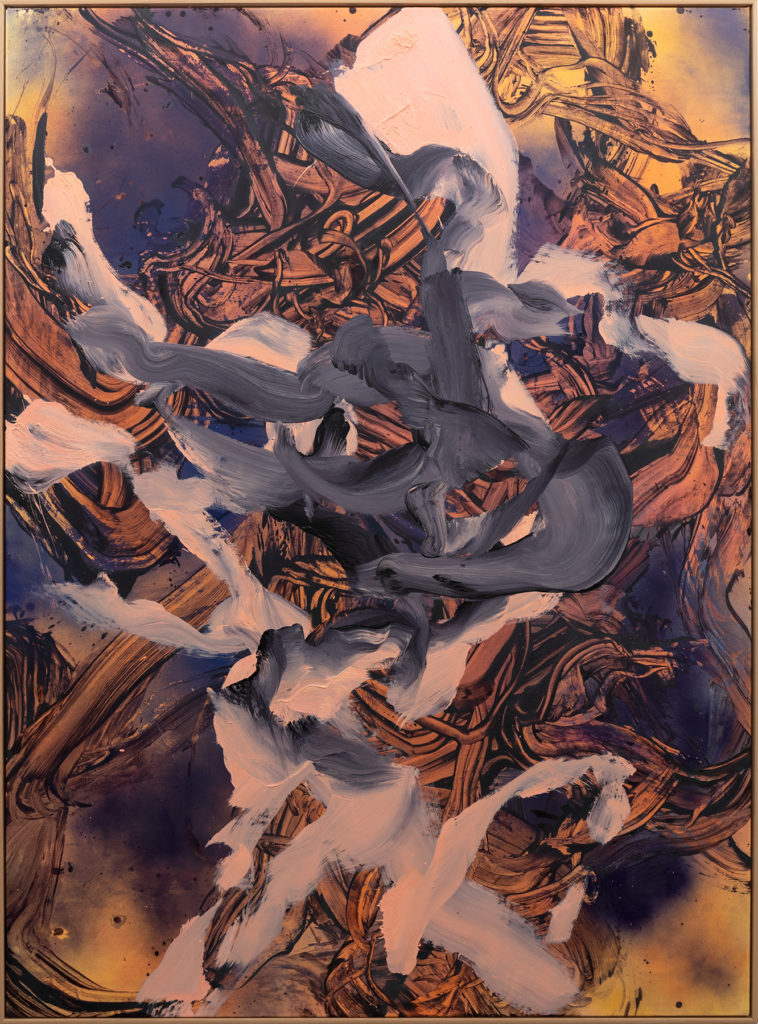

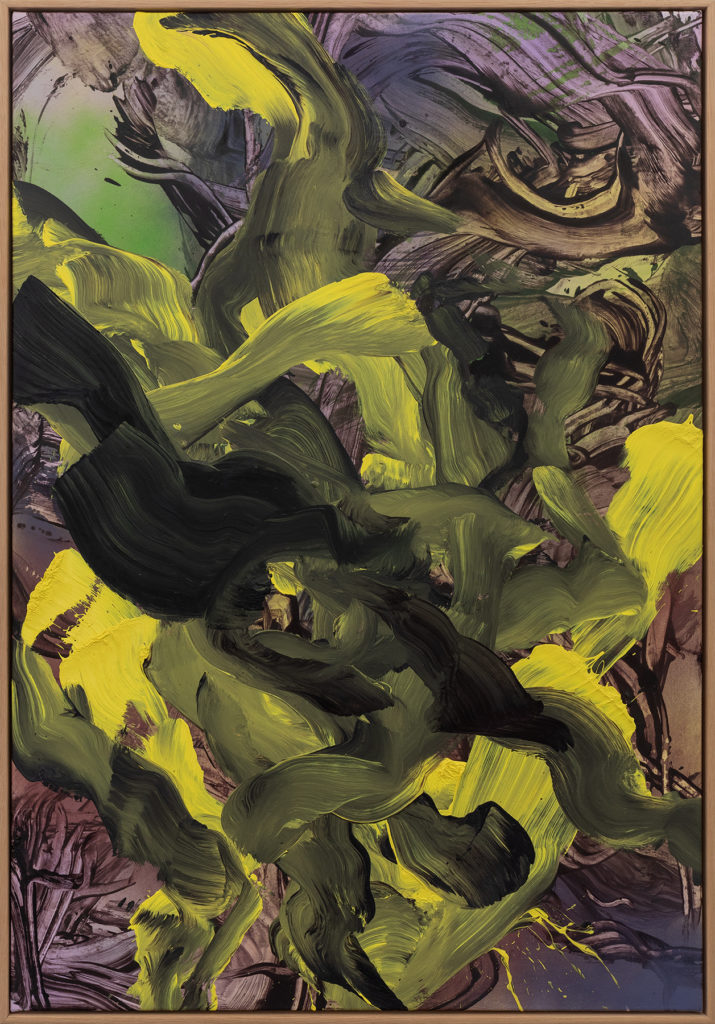

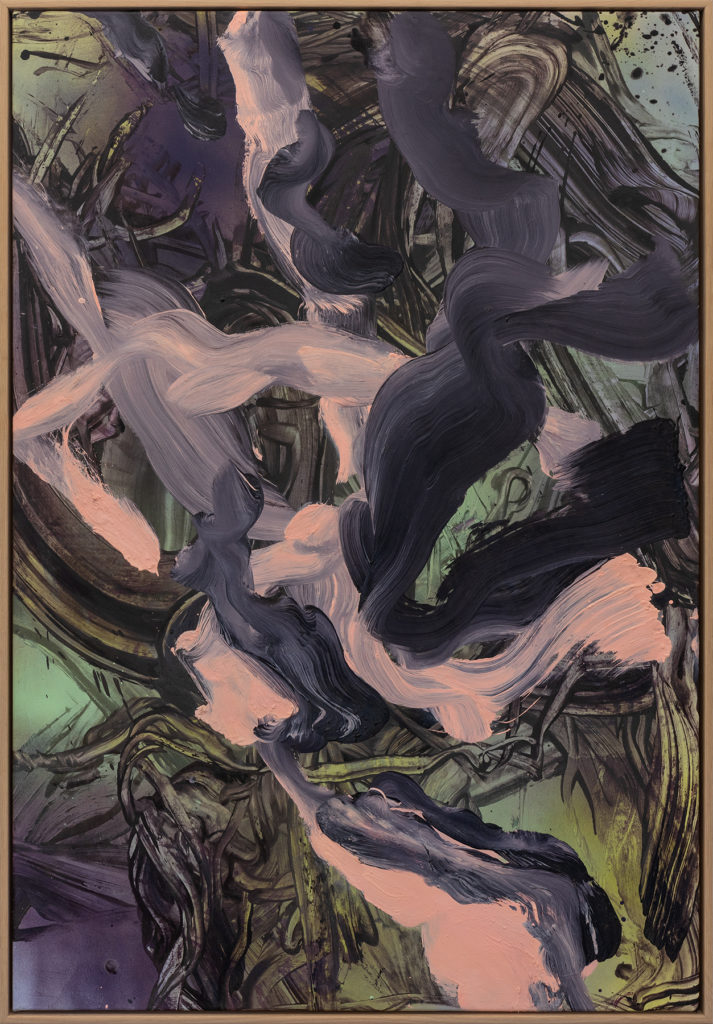

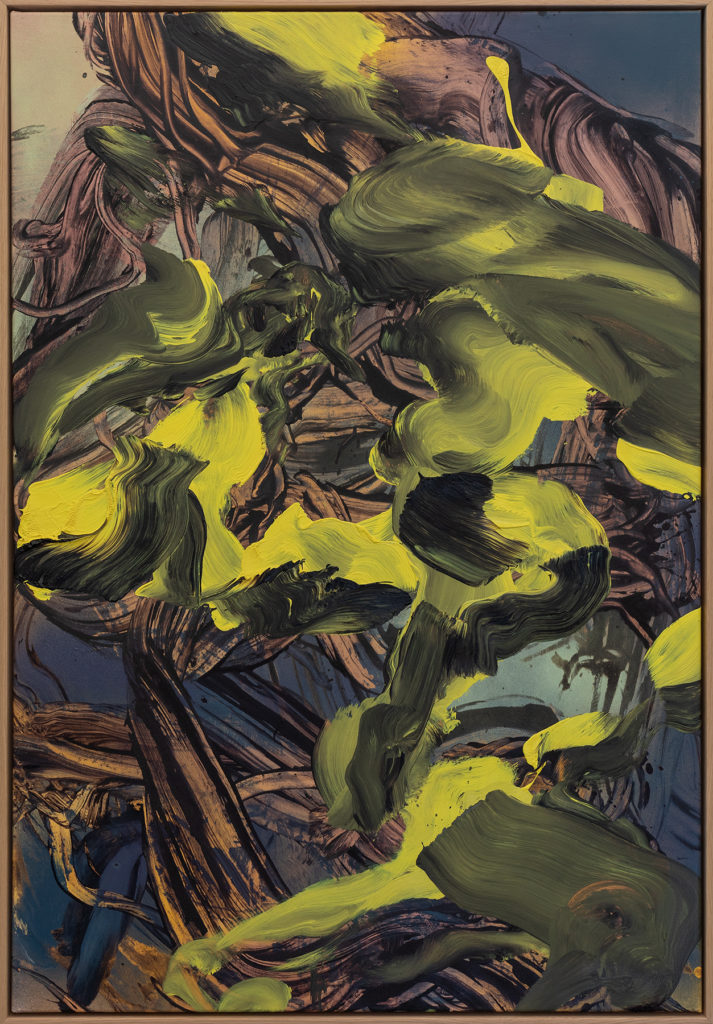

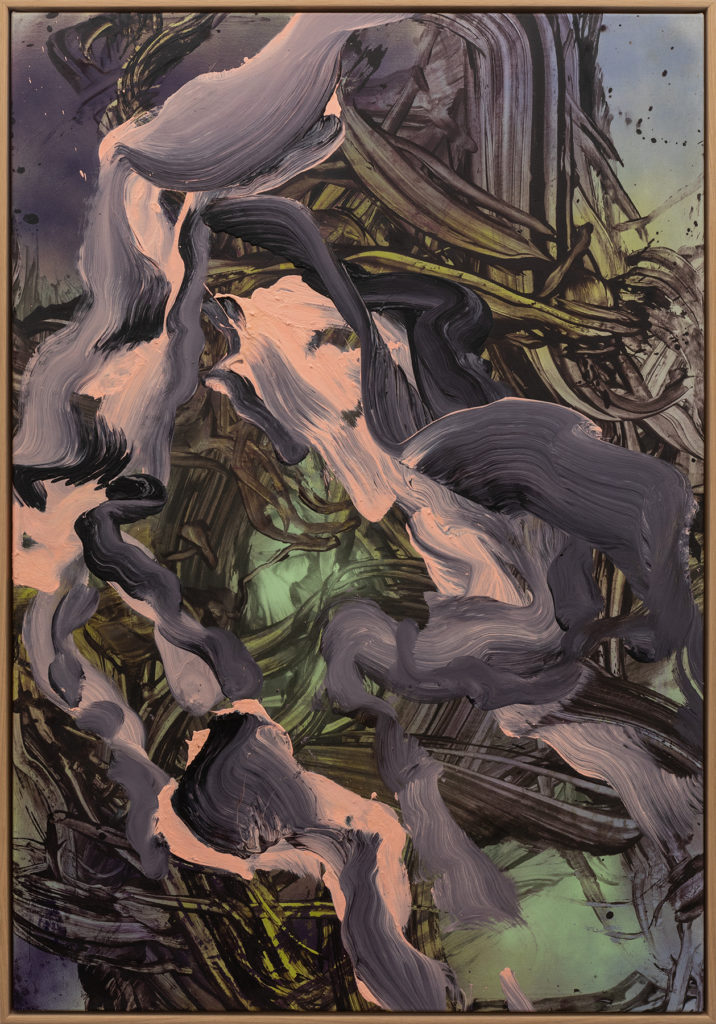

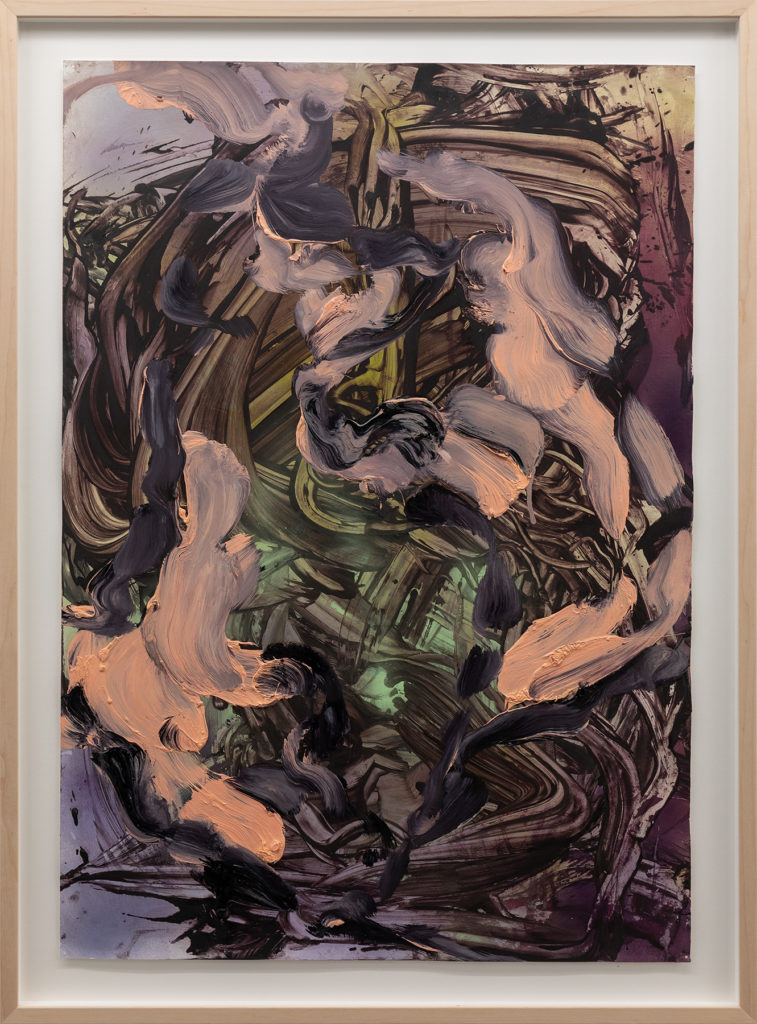

every attempted annihilation of the image makes it richer

Six large-scale paintings from the past two years come together in the gallery’s main room. Shifting between soft pastel tones and rich violet, blue, and yellow hues, a connecting element is constituted by the ribbons and lines stretching searchingly across the surface of each painting. Like a snapshot of an endlessly moving shadow, the colors applied in part directly by hand bring the duality of Judy Millar’s artistic undertaking into focus: on the one hand, the acrylic and oil paints are clearly visible due to their tangible materiality, as is the canvas as a given and confined image carrier. The paint and its layering are thus traceable and sometimes even addressed in works such as Untitled – Paintover (2020). The paintings are clearly set within a material reality that neither conceals nor masks the fact that they are “made”. On the other hand, both color and canvas are a means to an end that allows the artist to enter a world of illusion, a second reality, in which she confronts us with the works’ incredible depth and irrepressible pull. The painterly gestures seem to reach beyond the edges of the canvas and take on a life of their own. At the same time, each gesture serves a careful attempt to question what is actually visible (and what is not), as Millar seeks to obscure, conceal, and annihilate. Color, too, has a dual function since it serves as both a medium and a mood of sorts. In this respect, the hues and nuances of color evoke an atmospheric or affective tipping point: on a temporal level, by recalling the moment of dusk or dawn for instance, as well as spatially, as an in-between space oscillating between material fact and elusive dream.

I am a painter except when I am painting, then I am no-one, no-where, nothing

The exhibition title is borrowed from the eponymous publication, which brings together Judy Millar’s key works from the past forty years as well as notes and drawings from her workbooks. The written excerpts and thoughts that she shares in this catalogue express the exceptional “push and pull” of her thinking and ideas. This tension is just as inherent in her paintings: they convey what is probably one of the most fundamental contradictions of humankind, since we both exist corporeally and inhabit a mental, fictitious world at the same time. It is precisely on this threshold between materiality and illusion, the known and the unknown, the familiar and the new, that Millar explores the visible and the invisible realms through her work. Her paintings are thus able to conjure a heterotopic counter-site or a placeless place, so to speak, that brings together two colliding realities. The artist herself might describe this place as “no-where”. But even nowhere is indeed somewhere.

Marlene Bürgi

[i] The following quotes are excerpts from the catalog published in 2021 entitled “Questions I Have Asked Myself” by Judy Millar, which not only gives its name to the exhibition at Galerie Mark Müller, but is an important point of reference.

[ii] Georges Didi-Huberman, Atlas: How to Carry the World on One’s Back, Exh.cat. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2010.

[iii] Although the concept of heterotopia is highly contested, some theorists have explored it, while acknowledging its incompleteness and lack of clarity. In this particular context, it serves as a possibility to converge two independent spheres – an actual site (the painting as such and its materiality) and a counter-site (the world of painterly illusion and fantasy) in order to become a namable entity. Michel Foucault writes and talks about heterotopias on three different occasions between 1966 and 1967. The most well-known explanation of the term is given in a lecture entitled “Des Espace Autres” in March 1967 to a group of architects. See Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias”, in: Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

[iv] Foucault 1984, 3. Moreover, Foucault describes a bewildering set of examples, including utopian communities, ships, cemeteries, brothels, museums, prisons, gardens of antiquity, fairs and many more.

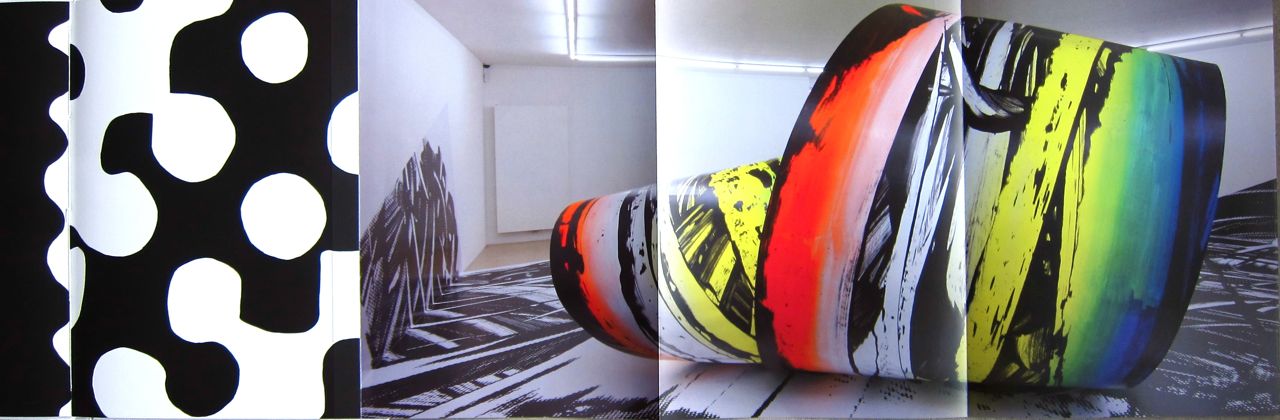

‘Expanded Canvas’ is a major exhibition at Town Hall Gallery exploring the dynamic and innovative nature of contemporary painting.

The traditional grid and two-dimensional picture planes are replaced by modern surfaces, including drop sheets, sign vinyl, virtual space, and the gallery wall itself. Colour spills, splatters, pools and stretches through the gallery space, in artworks that challenge possibilities of scale, form, colour and gesture. Pigment and brushwork are combined with elements from design, sculpture, animation and textiles to create vibrant and unexpected three-dimensional, virtual and ephemeral artworks.

‘Expanded Canvas’ showcases the ideas and aesthetics that characterise painting practice today, including artworks that reveal the continually evolving nature of the medium when fused with other disciplines and materials.

Featuring: David Harley, Lara Merrett, Judy Millar, Tom Polo, Bundit Puangthong and Huseyin Sami.

Whipped Up World – Review Mark Amery – Stuff 19 February 2022

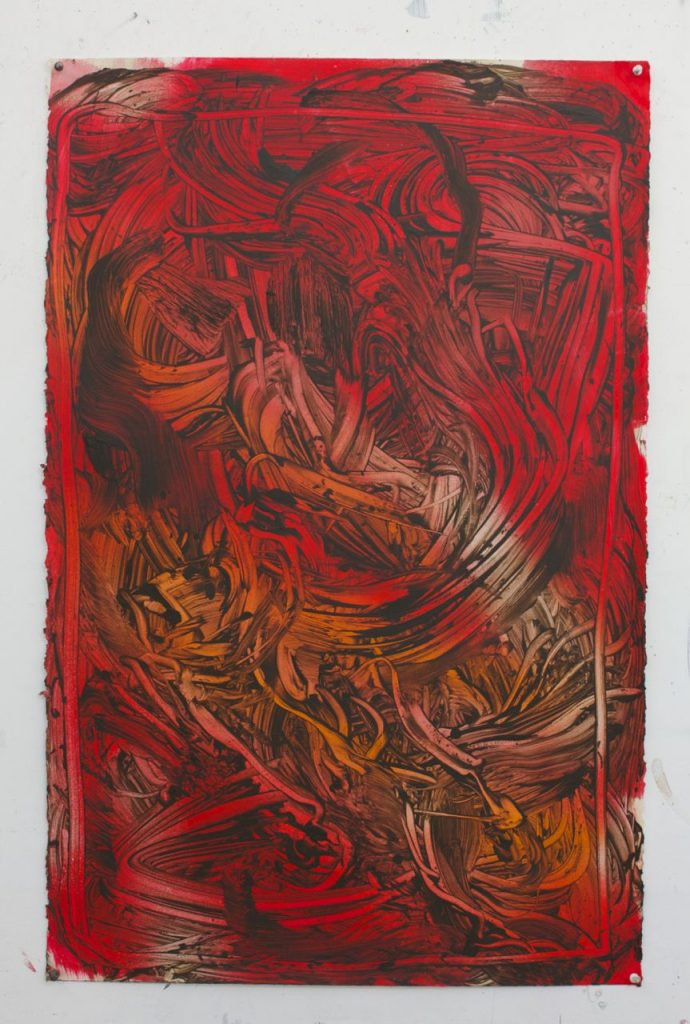

The title of Millar’s show at Robert Heald Gallery, upstairs in Cuba Street’s Left Bank, speaks straight to my sense of the state of things this week: Whipped up World. At their best, Millar’s large expressive gestural paintings have an extraordinary ability to express a physical and metaphysical experience of space and time, as if unlocking a different dimension.

There are two distinct sets of work here, demonstrating different pulls in Millar’s work. In the first room is the more familiar: a dominance of lithe yet muscular movement of whipping wiped strokes, twisting in and out of deep space. Millar’s abstract work has a highly evolved natural engine of its own. These strokes are at once moving skeletal body parts, sparking twisting electrical synapses, and DNA strands crackling in construction, all set within a rainbow bath of exquisite colour to be found where the ocean meets sky at dusk and dawn.

In the second room, on bigger canvases, the works are denser, with tension and obscuration caused by thick bright slaps of paint, congealed on the surface over deeper stormier pools. There’s nothing calming here – it’s big weather conflict, as if human and nature are in struggle, and the artist meditating through action – as one title puts it – on a ‘’Doubtful Sea’’. I’m put in mind of Millar as a gardener. I find these works harder to resolve as an experience, but there’s something rewarding in the almost physical struggle they put me through.

For me every time I make a painting I’m dragging the whole history of painting with me. I identify with Quentin Tarantino. His films refer to films, to the whole back catalogue of cinema. A black limo appears and it’s more than just a gangster mobile, it’s every gangster mobile that’s ever been in any film. You have the whole history of the genre there immediately. Tarantino sees clichés as a rich shorthand. It’s like the brushstroke in my work, or the drip, or the splash. They’ve already been played out endlessly. But while they could seem thin, I want to redeem their richness. I want to pick up those things and use them invested with everything they have ever stood for.

—Judy Millar, 2005

Harold Rosenberg famously coined the term ‘action painting’ to distinguish the work of heroic abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock. In his 1952 essay ‘The American Action Painters’, he explained: ‘At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act … what was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.’ Rosenberg’s idea would have a huge influence, especially on artists who would carry the idea into the realm of performance. These days, however, we are critical of the idea of painterly gestures as direct expressions of feeling. We tend to see them as signs of ‘expression’—as pictures.

Auckland painter Judy Millar, however, wants to keep the baby and the bath water. Her paintings seem at once intensely physical and vital and highly mediated and mannered. Millar famously ‘paints backwards’, wiping paint off her canvases to create exaggerated, hyperactive brushstrokes that seem to float in illusionistic space. Full of drama, her works breathe life into the discredited idea of action painting—she’s a reanimator. Action Movie showcases two new series of paintings—three mural-size paintings in hot reds and pinks and seven portrait-format paintings in colder hues. The ‘hot’ ones started with the idea of making a sequence of painterly gestures as a framed ‘comic strip’. The ‘cool’ ones are hung in a line suggesting frames in a length of movie film.

Action Movie presents Millar’s paintings in conversation with two ‘direct’ films inspired by abstract expressionism, both made by painting directly onto film stock. Len Lye’s ‘rhapsodic’ All Souls Carnival—a collaboration with composer Henry Brant—was made using felt-tip pens and lacquer. In 1957, the film was projected on a screen behind musicians performing a Brant composition at New York’s Carnegie Recital Hall. Inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy, The Dante Quartet (1987) took American experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage six years to produce by painting images directly onto IMAX and Cinemascope 70mm and 35mm film stocks. In both films, the idea of painterly expressivity is complicated by being scrambled with the mechanics of cinema. Brakhage foregrounds this by slowing down and speeding up his footage, and by freezing frames.

Action Movie also includes films of artists in the wake of Pollock performing painting actions. From 1956 to 1966, Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, a key figure in the Gutai group, paints with his feet, while having onto a rope. In 1960, French artist Yves Klein employs women’s bodies as paint brushes in Paris. In 1962, Italian artist Lucio Fontana punctures a canvas for Belgian TV. All three engage with materials only in order to transcend them. However, American performance artist Paul McCarthy’s approach is more abject: he paints a line along the floor using his face in 1972.

Millar’s paintings are placed in conversation with these films to prompt viewers to consider the way her work toggles between painting and performance, presence and absence, material and ideal, the spontaneous and the considered.

Curated by: Robert Leonard

All images: Cheska Brown

4 August – 28 August 2021

The works for this exhibition were, for the most part, painted during the year 2020. A period that will be forever bracketed in our hearts and minds as the year of the pandemic. A time when the world went eerily quiet. A time when we were forced to find new relationships with our immediate surroundings.

I spent the year in my isolated home and studio on Auckland’s West Coast. Time slowed. My own focus was on the simplest of things. The movement of clouds. Making fire to stay warm. The light on the water outside my window. Wind and air.

Painting for me is always an attempt to grasp hold of something. As I took the colours of fire, mixed paint to the fluidity of water, produced clouds of coloured spray and attempted to aerate the surface of the canvas into an open space; the solidity of things moved in and out of focus. Forms emerged on the canvas but had a fleeting feeling, as if they were about to dissipate or perhaps hadn’t yet fully formed. Red moved to pink and then back to red. Everything seemed to be in motion. The resulting paintings together form a group where movements continue from one to another, read in this way they become a form of moving landscape. Individually they are snapshots of a particular time and place.

In 1972 Alberto Garcia Alvarez arrived in Auckland from California having been invited here as a guest lecturer at the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts. Alberto went on to become a Senior Lecturer at Elam, retiring from the position in 1995.

During his tenure at Auckland University Alberto was an influential teacher. He was sought out by students who were drawn to both his knowledge of international contemporary painting and his deeply curious and enquiring personality.

Judy Millar and Stephen Bambury were two students who found a kinship with Alberto’s relentlessly questioning mind. Both came to regard him as a crucial figure in their own independent artistic developments.

This exhibition featuring the work of Alberto Garcia Alvarez and Judy Millar has been curated by Stephen Bambury and so brings the three together in a public dialogue for the first time.

The exhibition will focus on two distinct periods of Garcia Alvarez’ and Millar’s work. Paintings produced by Garcia Alvarez during his time in California in the late 1960’s have been selected by Bambury to sit alongside paintings painted during the last few years in his Auckland studio. Millar will exhibit work from 1981 when she was a student at Elam together with a number of recent paintings.

The exhibition will be held contemporaneously across both Gow Langsford Gallery, Kitchener St, Central Auckland and Tim Melville Gallery, Winchester St, Newton, between August 4th to August 25th 2020.

A catalogue will accompany the exhibition containing previously unpublished writings by both Garcia Alvarez and Millar.

In 1971 an exhibition of 10 Big Paintings opened at the Auckland Art Gallery. All the exhibited artists were men. 50 years later Millar has painted the eleventh work for that exhibition.

The work was painted during the last months of 2019 as Millar felt urgency in the air and rolled out the largest canvas she could across her studio floor and got to work.

The situation of our current times as Covid-19 creates havoc and heartache across the planet is beyond anything she could have imagined.

http://www.roberthealdgallery.com, Wellington, New Zealand. Opening 12 March 2020

“Untitled, 2005, is both an extraordinary painting in its own right and a key pivotal work in Millar’s œuvre. Alternatively celestial or oceanic, it marks a critical juncture in her practice coincident with the consolidation of her on-going commitment to presence in both Aotearoa New Zealand and Germany and Europe. While pronounced now, this wasn’t necessarily quite so marked when it was first shown in an expansive and experimental exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery “I will, can, must, may, would like to express”from September to November that year. It was the most difficult painting in the exhibition, a building site painting or work in construction as Millar described it in an accompanying exhibition brochure. Certainly unruly, anarchic, even within an exhibition that challenged assumptions as to what painting might entail, it escalated the core motivations of her practice at that time. In an exhibition filled with actual and potential jumping off points, this painting was the most extreme, the most risk-taking and, in a very precise sense given it is such an important concern for the artist, in retrospect it seems to have been the most present.”

P. Shand 2019

18th May – 18th August 2019

In 1965 Roy Lichtenstein created his famous brushstrokes and in so doing transformed the subjective gesture of heroic Modernism into a trivial comic drawing, transposed into the large format of a museum.

Konrad Bitterli, Lynn Kost, and Andrea Lutz curate the extensive Frozen Gesture exhibition – a sheer range of gestures in contemporary painting, presented by Kunst Museum Winterthur. The exhibition brings together important individual pieces by outstanding protagonists of Abstract Art, such as Gerhard Richter and David Reed, with extensive work groups of contemporary artists such as Franz Ackermann, Pia Fries and Judy Millar – to create a fascinating display of works of exceptional painterly quality and inconceivable sensory appeal.

The spontaneous movement of the brush on canvas mutated into a quote, the emotional exploration of depth morphed into a Pop surface in signal colors. The purported immediacy of the expressive painterly act thus became an ironic reflection on the medium of painting using the means of mass culture.

This distanced and self-reflective approach had defined contemporary painting since the end of Modernism. It highlighted the fundamental elements of the image, such as the appearance of the colors and the pigment, the color fields and their limits, and not least the application of paint in the form of a gesture.

This gesture had long since abandoned directly expressing existence in favor of any number of different discursive strategies and painterly approaches. To this day, artists underscore the problematic nature of the impact of the application of color and are forever reinterpreting it – from the gesture as a semiotic abbreviation for painting through to its diverse transformations in images.

Curators: Konrad Bitterli, Lynn Kost, and Andrea Lutz

Galerie Mark Mueller presents the group exhibition Single, but happy. Zurich, 8th June – 20th July 2019

“An oversized painting will frequently dominate the room in which it hangs, engulfing the viewer physically and, often, emotionally. Gow Langsford Gallery presents Enveloping Scales, an exhibition of five paintings that consider the act of looking when viewing large format works. Each work typical of their maker’s practice, Reuben Paterson’s Whakapapa Get Down on Your Knees, John Pule’s Not of this Time (Dreamland), John Reynold’s Liberty During Construction, Judy Millar’s The Principle of Straight Branches and Jeffrey Harris’ Of Time and Ambience all evince the affective qualities afforded by large scale painting.

When confronted by a really big painting, the eye is unable to take in its entirety at once. Judy Millar’s Ring in the View introduces the vertical axis in the viewing experience – forcing her audience to look up. Drawing inspiration from Auckland’s west coast beaches, Millar’s painting invokes the tempestuous skies, swamping the viewer.”

17th April – 11 May 2019

Judy Millar, March 2019

I was sitting down to write up notes about this exhibition on March 15th when headlines wrote themselves across my screen. A man and a gun had vented rage and hate against fellow New Zealanders in their time of prayer.

Times like this make you question a life in art, a life that is in itself a kind of devotion. It can seem to lack the necessary force to counter-strike. It can seem too invisible as an influence on everyday life.

The seeming inadequacies of art became even starker when I began to view this desperate act of violence as part of a broader picture appearing around the world. We have long lived in a world that has assumed white superiority but it is fast ramping up, in so many parts of the world, into an outright declaration of supremacy.

We are living in a time where democracy itself seems challenged if not directly threatened. We have reached a point where we make enemies of those who hold different political perspectives than our own. We live in a time where we ‘unfriend’ those who challenge or criticise us. Where we object to listening to opinions we don’t already fully agree with and where we respond with outrage to views that clash with our own. All of these attitudes and behaviours run counter to the core democratic principle of respect for differing opinions.

I have always believed that involvement in art is primarily about absorbing different points of view. Being open to art is about gaining the flexibility to look at things from all sides and in doing so to nourish our empathic humanity. But on March 15th I once again had to ask – is this enough?

I still don’t have an answer to that question but while thinking deeply on this over the ensuing days I stumbled on this quote from Simone Weill. In her Notebooks she writes that we are helped by meditating on “absurdities which project light”.

For now this definition seems a suitable definition for art, and one that can give me some hope as to art’s ongoing importance. At the very least I will take it as a definition of my own project.

I have worked hard to light these canvasses from the inside out. I have sought to combine the paradoxes of coloured earth and a suggestion of the immaterial. I have desired a feeling of space and surface coexisting. I have tried to evoke dusk – the time of day that is neither day nor night but is both at the same time. I have wanted to suggest a multitude of things and nothing at all.

I know this is not enough, but for the interim it is what I can offer. I hope that it will encourage contrasting viewpoints. In doing so it might enable the widening of our individual perspectives.

REVIEW

Judy Millar arbeitet sich an der Malerei ab, zerlegt die Geschichte und die Techniken des Mediums. Damit wurde sie zur wohl bekanntesten Künstlerin Neuseelands. Das Kunstmuseum St. Gallen widmet ihr nun die erste große Einzelausstellung außerhalb ihres Heimatlandes.

Judy Millar, Don’t Call Me Baby, Baby, 2002, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Nach eigener Aussage geht es Judy Millar darum, ihren Platz in einem Genre zu finden, das für sie in ihrer persönlichen und künstlerischen Entwicklung keine Vorbilder bereithielt. Der Blick zurück in die Kunstgeschichte der Malerei war für sie primär europäisch und männlich geprägt. Als neuseeländische weibliche Künstlerin hinterfragt sie diesen Kanon distanziert, dekonstruiert ihn bis ins Detail und entwickelt dadurch einen eigenen unverwechselbaren Stil.

Judy Millar, Untitled 2005, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Dies zeigt sich bereits an der für sie typischen und sehr individuellen Arbeitsweise, die durch einen Prozess des Wegnehmens geprägt ist. Damit kehrt sie das grundlegende Prinzip der Malerei um: Aus dem additiven Auftragen von Farbe und Material wird ein nicht minder ausdrucksstarker Vorgang der Substraktion. Auf den ersten Blick erinnert der Duktus der Gemälde an intuitiv und dynamisch aufgetragene Pinselstriche. Tatsächlich trägt die Künstlerin Schichten von Ölfarbe auf die Leinwand auf und nimmt diese mit Stoffbahnen oder mit Sand gefüllten Plastiksäcken wieder von der Oberfläche ab. Dies sei − ganz anders als der erste Eindruck vermuten lässt − ein sehr langsamer und kompositorischer Vorgang körperlicher Anstrengung, erklärt Judy Millar. Und tatsächlich sind die in den Werken manifestierte physische Präsenz und der gestische Ausdruck unmittelbar für den Betrachter spürbar.

Millar pendelt zwischen Auckland und Berlin und identifiziert sich mit der aus der räumlichen und charakterbezogenen Distanz entstehenden Ambivalenz der beiden Orte. Zwischen der großflächigen Landschaft Neuseelands und dem dazu in Kontrast stehenden Leben in der Großstadt bildet sie ihre künstlerische Identität und zieht ihre Inspiration für neue Arbeiten. Die großformatig angelegten, raumgreifenden und extra anlässlich der Ausstellung „The Future and the Past Perfect“ in der Kunsthalle St. Gallen konzipierten Arbeiten „It to Them, to Us to I“ konnten somit nur im Kontext der neuseeländischen Weite entstehen.

Judy Millar, It to Them, to Us to I, 2018, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Dabei interessiert die Künstlerin auch das Spannungsverhältnis zwischen Malerei und Architektur. Die Werke sind bewusst überdimensional gestaltet und scheinen die mit Stuckelementen und Bordüren geschmückten Räume des Museums regelrecht zu sprengen. Gleichzeitig geht es Judy Millar dabei aber nicht um eine skulpturale Ebene von Malerei. Sie sieht ihre Arbeiten explizit als Gemälde an und will sie nicht als genreübergreifende Objekte verstanden wissen. Die Kunsterfahrung soll sich deshalb auf die frontale Betrachtung der eindimensionalen Leinwände beschränken. Ein allseitiges Begehen des Raumes, um einen Blick auf die Rückseite der Werke zu werfen, ist gerade nicht intendiert.

Bei Judy Millar geht es in vielerlei Hinsicht zunächst um die Herstellung von Referenzen durch Nachahmung, welche durch eine eigenständige Interpretation aufgebrochen werden. Besonders deutlich wird diese Herangehensweise an Millars Auseinandersetzung mit der Kunstgeschichte der Malerei. Es zeigt sich an der Optik perfekt durchgeführter Pinselstriche, die gar keine sind. Vor allem die jüngeren Werkserien scheinen besonders impulsiv kreiert, beruhen jedoch wie alle Arbeiten der Künstlerin auf einer bewussten Farbauswahl und Durchführung der einzelnen Arbeitsschritte. So wird der Betrachter immer wieder dazu veranlasst, seine eigene Wahrnehmung zu hinterfragen und einen neuen Zugang zur Malerei zu finden.

WANN: Die Einzelausstellung der Künstlerin mit dem Titel „The Future and the Past Perfect“ ist noch bis zum 19. Mai zu sehen.

WO: Im Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, Museumstrasse 32 in 9000 St.Gallen.

Diese Review entstand in freundlicher Zusammenarbeit mit dem Kunstmuseum St. Gallen.

“The gestural and abstracted surfaces of Judy Millar’s art are both intensely physical and highly mediated structures, reflecting the paradox we face of inhabiting both corporeal and cognitive realms.

Millar, a distinguished and internationally acclaimed artist, employs the processes of erasure – wiping and scraping paint off the surface of the work – to create visceral canvasses that invoke a sense of the body.”

art_messenger 2019

2nd March – 19th May 2019

The Kunstmuseum St Gallen is offering an overview of Millar’s entire oeuvre, which she has created in Auckland and partly in Berlin over the past forty years. Together with her well-known serial paintings with expressive brushwork and broken up spaces, the artist has created a spatial installation of paintings for the Skylight Hall. A surprise is the early abstract geometric drawings from the 1980s shown for the first time in Europe.

Curator: Roland Waespe

More information.

For Art Basel Hong Kong 2019, Gow Langsford Gallery presents a selection of work that demonstrates the late New Zealand painter Colin McCahon’s legacy and considers his practice in relation to his International contemporaries.

Can you tell me what you’ve been working on for the show?

I am showing new paintings, not exactly made with this show in mind but certainly indebted to McCahon. His oeuvre is so vast and rich that any painter working in New Zealand will find themselves conscious of his presence over and over again.

I recently finished reading Knausgard’s A Time for Everything in which he retells biblical stories, setting them in his homeland. I live on the Tasman seacoast not far from where McCahon painted most of his late works centred on religious texts. The mix of bible story, angels, Noah, coastlines, gannets and rising waters seems to have filled my imagination this summer.

“The telling of great stories set in your own backyard has lead me to seriously reconsider the importance of place. My own works have become increasingly infused with West Coast Auckland. The landscape is always there.”

How would you describe McCahon’s legacy within New Zealand art history?

McCahon was a visionary. He brought an ambition to his work that sought to match the great painters of history. Through his commitment, he laid the ground for art to become a serious undertaking in Aotearoa [New Zealand]. For it to matter, because it spoke directly to an experience of the country as it was. It was as if he banged a stake in the ground and stood by it.

You were the first artist to take up the McCahon House Artist in Residence programme in 2006, which saw you move into a purpose-built studio just next door to the bach [a New Zealand term for holiday house] where McCahon and his family lived in the 1950s. What did you take from this experience?

This time was a complete turning point for me. The bach where the McCahon family lived has been turned into a small museum containing his archived correspondence and tapes of him talking about various things. As a resident you get 24-hour access to the museum. I would go very often at night and sit and listen to Colin speaking. It was as if he was talking directly to me. Telling me to wise up, get serious. It came at the perfect time in my life. In that house you know that art matters.

How does the idea of legacy – of leaving something behind you that has the potential to influence future generations – play into your practice? Has this changed over time?

I’m an art history junky and love to see how things have influenced and do influence other things. But I have the feeling we are in a new world. Everything is on the table now and the pathways of influence will become largely untraceable in the future I think.

What would you say is the most important issue facing New Zealand artists working today?

I think the biggest issue is, as for everyone else, is sustainability. Artists working in New Zealand need to travel a lot and that’s going to be increasingly difficult to justify.

We are also suffering in New Zealand from an absence of genuine critique. Increasingly we are divided into smaller and smaller interest groups that make rigorous expansive discussion impossible; this is making it very difficult to develop complex artistic practices.

13th Sept – 20th Oct 2018

The colour palate is double-edged; reminding us of the moments when nature thrills us with sunsets, sunrises and deep blue lagoons but also recalling the colours of comic books and their depictions of outer space adventure and future doom. Millar, a fan of popular science, describes the activity of painting as a form of space travel.

“I used to think painting was a way of thinking. Now I know it to be much more than that. It is the flash of big-brain meeting small-brain, of consciousness meeting thought or of consciousness meeting mind through the body. Of outer space and inner space colliding.”

In this new group of works form becomes the graph of activity. The appearance of “things” emerges from the web of painted lines and fields of colour. Things hard to name but fleetingly apparent establish a semi-believable pictorial space. These strangely spatial paintings exude an otherworldly luminosity as if emitting light from a distant time and place.

As Millar applies then removes layers of paint from the surface of the works she seems to release energy as if an image has been held in matter and is now freed into visibility.

Published September 2019

Judy Millar’s work has seen many forms, including large paintings that tumble from the gallery ceilings in large coils. For her first solo show in London, The View from Nowhere, she presents six paintings full of energetic and colourful works that include a signature process in which she removes layers of paint from the surface after applying it. Bob Chaundry talked to Judy Millar on the first evening of her show.

How did you prepare for this show, your first solo show in London?

I work all the time and I try to choose good work that looks the right scale for the room. So I built myself a little model of the gallery and I worked with differently sized paintings that I thought would have an interesting relationship with the scale of the room.

You are quite known for your leviathan size works.

I work in a huge range of sizes, from very small to very, very large. Every work in a way has to have an interesting relationship to the body, so whether it’s a tiny scale or a big one. I think painting is like a portal and can suck a whole room into it if it’s working well. So that’s the kind of relationship I’m always looking for. I want a tension between the pictorial surface and the space it occupies.

I’ve read that you compare the act of painting to space travel.

Yes, that’s my experience when I’m working. I really feel that space and time dissolve into one another and I almost become non-existent. I suppose in contemporary terms it’s like disappearing down a black hole which is a very amazing feeling.

Is that what some would call getting into the zone?

I think athletes refer to it that way. It’s a different sort of consciousness, you step into an entirely new way of being.

My first reaction on seeing your paintings was that they’re very organic.

I think they’re both organic and highly synthetic. I’m always trying to bring the most contrary elements together in a work as possible. So, on one hand they’re very organic, on the other they’re highly artificial and synthetic. On the one hand they’re very free in their making, on the other hand they’re very constructed. I think painting at its best can bring these very paradoxical activities into one image.

Why do you feel the need to have these opposing forces together?

Because I feel that that’s what painting can do, and it’s something that very few of the other media can do and that comes from the fact that painting is both an illusion and a physical being at the same time. That’s very unique. A film is not. You can’t reach out and touch a film, it vanishes. A book is only able to be understood through a process of time. With a painting you get it all at once and you can relate to it as a physical thing while at the same time it’s highly illusionistic and a mental construct.

“I think being human, one of the dilemmas of our lives is that we live in these two realms, the mental realm and the physical realm and that causes us endless problems.”

So we have our imagination and our dreams and our fantasies and we have to deal with the reality of tables and chairs and cars and roads and all those other things. Humankind has always had to do that and I think religion attempts to bring those things together and I think art is another attempt to bring those things together to try to understand our dual existence. For me, painting can really hammer that dual existence, it can really deal with it.

So, where does your inspiration come from?

Through a long, long involvement with both looking at painting, thinking about painting and making painting and from my experiences in the visual world. And then it’s my very intimate relationship with the material I’m working with. So it’s all those things coming together.

Do any particular artists influence you?

Every day someone new. Every show I see, someone new. It’s extraordinary to see, as I did in the National Gallery this morning, paintings you know quite well and then you see new aspects to them.

I see colours that I think could be useful, the way artists have loosened the world up. When I look at a painting I ask myself what are they seeing. How are they trying to re-see that when they work? What have they seen, what are they seeing, and how are they presenting that are questions I’m always intrigued by.

How do you go about constructing your paintings?

It’s very traditional in many ways. I start with lighter colours and work towards darker colours. Then I’m pulling paint off the surface so it’s really a matter of putting paint on and taking it off until I arrive at something that I recognise in a way. So it’s a to-and-fro process of application and removal.

Why do you remove paint?

I started off painting in the 1980s and it was a time when deconstruction was the mode. I wanted to discover for myself what was the minimum a painting could be. So I started to remove stuff and I’ve always stayed with that. It’s a bit like a fashion designer’s work undoing clothes and finding how they could deconstruct a garment and I was trying to do the same with painting.

But do you know which bit you’re going to deconstruct before you do it?

At that time I was trying to understand how far I could deconstruct painting and I ended up with works that were just marking tape and gesso. Obviously I’ve become much more involved with image since then but there is still that aspect of putting things on and stripping it away in order to get at something that is just enough and vital.

“I saw a fantastic Francis Bacon show in Basel earlier this year and he said I want to get as close to the nervous system as possible and that really resonated with me because sometimes you want to get so close that you put your whole body in there.”

That’s when your hand will just go into the paint. You want it be as close as possible to your body. I work on the ground, it’s all very fluid. It’s quite physical, I need to use a lot of force. I walk into the works if they’re very big and paint my way out of them. I’m always finding new kinds of things to use to move the paint. I use rags and brushes and I use spray and tools that I invent and tools that I find and my fingers and feet and everything else. It’s a dirty business (laughs).

So beneath these layers of paint is a nervous system

When my hand is in the paint obviously the connection of the paint and my nervous system becomes one thing. The image becomes just the extension of the nervous system in a way.

Born in 1957, Judy Millar has become one of New Zealand’s best-known painters, representing her country at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009. Her work has been exhibited not only throughout her own country but also in Europe and the United States to much critical acclaim.

Source | More from Bob Chaundry

The View from Nowhere is showing at the Fold Gallery, 158 New Cavendish Street, London W1W 6YW until 20 October 2018.

Without the shock and awe of leviathan size these works must be on point. And they are.

https://www.newsroom.co.nz/@living-room/2018/08/24/207068/never-neutral-abstraction-in-auckland

“The first ‘coast works’ in their primary saturations have remained unseen by anyone else since the late 1980s. They have been harshly edited over the years with many being burnt. Those remaining seem now to be a nucleus of thoughts and responses that have emerged decades later.”

9th September 2017 – August 2018

Unconventional and experimental approaches to the age-old discipline of painting

Despite routine declarations of its decline, abstract painting is an urgent and vital mode of artmaking that seems to exist in a state of constant reinvention.

This exhibition surveys Art Gallery NSW’s rich holdings of contemporary abstraction, including artworks by Daniel Buren, Morris Louis, Judy Millar, Dona Nelson and Sigmar Polke among many others.

Unpainting brings our attention to the Gallery’s extraordinary holdings of abstract paintings, focusing on unconventional and experimental approaches to the medium from the 1960s to the present day.

Curator Nicholas Chambers’ introductory essay in the accompanying publication proposes six frameworks to consider the selected works – unpainting, unhinged, unmanned, untitled, unravelling, unending – which highlight an attitude of experimentation, unbound to convention and often underpinned by a restless desire to disrupt the standards of the day.

Three of the contributing artists – Dona Nelson, Christine Streuli and Jessica Stockholder – are also interviewed about their practices and their works in the exhibition.

Exhibiting Artists:

Mark Bradford, Daniel Buren, Ian Burn, N Dash, Angela De La Cruz, Mikala Dwyer, Dale Frank, Katharina Grosse, Wade Guyton, John Hoyland, Albert Irvin, Bob Law, Richard Long, Morris Louis, Judy Millar, Dona Nelson, Sigmar Polke, Mel Ramsden (Art & Language), Robert Rauschenberg, Ugo Rondinone, Josh Smith, Frank Stella, Jessica Stockholder, Christine Streuli, William Turnbull, Andy Warhol.

AGNSW Contributors:

Nicholas Chambers – Senior Curator

Lisa Catt – Assistant Curator of International Art.

A group exhibition lapping at the shores of heteronormative sanctity, curated by Kate Britton

Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

18th August 2018 – 15th September 2018

The Waves borrows its title from Virginia Woolf’s novel of the same name, in which many voices unite in a single narrative. This exhibition likewise unites many voices to tell a single yet multivalent story. This story is about what happens in a white cube occupied by women and non-binary voices, and why we should be listening.

The Waves brings a diverse group of artists into a conversation about feminism, bodies, access to and occupation of space, collective action and gestures of intersectionality. In making their work, each of these artists chip away at the walls and barriers that are thrown up by patriarchal systems, biological determinism, trans-exclusionary feminism, colonialism – the list goes on.

The feminist project has been characterised by waves, a lapping at the shores of heteronormative sanctity. The works presented from these artists engage with different aspects of this project: political, social and labour-based action; reclamation and celebration of diverse bodies and identities; intersectionality; and an emergent collective anger – #metoo.

In bringing together work from Sullivan+Strumpf artists with invited artists, The Waves establishes new lines of sight between the work of diverse women and non-binary people.

Karen Black

Ohni Blu

Polly Borland

Barbara Cleveland

Christine Dean

Joanna Lamb

Lindy Lee

eX de Medici

Sanné Mestrom

Judy Millar

Dawn Ng

Thea Perkins

Katy B. Plummer

Justine Youssef & Leila El Rayes

Hiromi Tango

Angela Tiatia

Jemima Wyman

Studies in Place: Works on Paper 1989 & 2017

8th August – 1st September 2018

Studies In Place – a solo exhibition of small works on paper from 1989 and 2017 held at Gow Langsford Gallery. The works from 1989 show Millar’s immediate response to the wild landscape of Auckland’s West Coast when she first moved there soon after leaving art school. The recent works track her newfound reflection on the importance of place; place not only considered as a location but more importantly as a set of determining circumstances.

“I seemed to spend the greater part of my early life searching for a place to look out at the world from. My favourite childhood game was a blanket draped over the family dining table providing a place in which I could secure myself. Hidden within the folds of fabric I could create a new realm that gave me the privacy I longed for.

Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own” later confirmed it for me. Every woman needed a space defined for her, by her.

What it was that pulled me to Auckland’s West Coast as a young person I’ll never be completely sure. But there I found the mental freedom I longed for – a freedom that let me define my own existence as if back in the blanket hut. The wild storms neutralised by own inner turmoil: an external and internal pressure meeting and rebalancing one with the other. The sound of wind in the trees and crashing against the house became a valve that allowed me to inhale and exhale more fully.

Then the visuals – the views from up high as if floating above the land. The colours that changed throughout the day reaching a new saturation as each day’s sun set. Overwhelming, yes. But life giving too and so as I began to work I found my body respond in new ways.

The first ‘coast works’ in their primary saturations have remained unseen by anyone else since the late 1980’s. They have been harshly edited over the years with many being burnt. Those remaining seem now to be a nucleus of thoughts and responses that have emerged decades later.

All these small works are the direct result of being in a place: a place that has become my intimate world. The trees and plants have grown with me, around me. The wind has screamed at me and I at it. From the garden I eat. The sea air has seasoned my lungs well. I have both arrived at and imagined a place.”

Judy Millar solo exhibition, Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney, Australia

6 April – 28 April 2018

The gestural and abstracted surfaces of Judy Millar’s art are both intensely physical and highly mediated structures, reflecting the paradox we face of inhabiting both corporeal and cognitive realms.

Millar, a distinguished and internationally acclaimed artist, employs the processes of erasure – wiping and scraping paint off the surface of the work – to create visceral canvases that invoke a sense of the body.

“Without our body we don’t exist, this to me is our experience of the world and this is what paintings can directly address.” – Judy Millar

Millar’s painterly practice also incorporates various printing techniques and digital reproduction, which allow her to push the possibilities of scale by enlarging and exaggerating the painted surface. Through exaggerations of scale, her expressive paintings saturate the viewer and become commanding expressions of embodiment.

By Mary-Louise Browne.

Judy Millar is considered by many to be a formalist in that her work addresses itself to painting, the perceived problems of painting and issues surrounding the history of painting. At the same time, as she talks about the vitality and ‘eye-searing magic’ of painting, she brings to her work a theoretical and practical interest as to where she fits in the male-dominated tradition of painting as a woman artist in the 21st century. As one of New Zealand’s most internationally recognised artists, she makes explicit the engagement of her painting with the rest of the world.

Her work looks outwards rather than in, participating in a global conversation about the relationship that painting has with the real world it both seeks to represent and be a part of.

She works from within a conceptual painting framework, freely referencing painting’s modern developments and relishing in appropriating the expressiveness of gestural painting. Continuing to explore possibilities in the action-painting tradition, she uses gesture not as personal expression but as a basis of social exchange. A sense of performative drama and delight in the act of mark-making is evident in this painting. The physicality of the gesture in Millar’s work is reminiscent of that of Jackson Pollock and she regards the direct relationship of the body to the canvas as extremely important. Also, painting for Millar is fundamentally a process of unpainting; perversely, her artworks are unworked rather than worked up – she takes away as much as she adds. Utilising processes of erasure, wiping or scraping paint off the surface of the work, Millar assumes established sociological and cultural positions only to question and deconstruct their meanings. She challenges the viewer’s expectation of the ‘expressive gesture’ and of the effectiveness of painting as a contemporary means of communication.

The physicality of the gesture in Millar’s work is reminiscent of that of Jackson Pollock and she regards the direct relationship of the body to the canvas as extremely important.

She has said of her practice: “It’s ‘embodied painting’. Without our body we don’t exist, so that seems to me to be our experience of the world. And that is what painting can directly address”¹

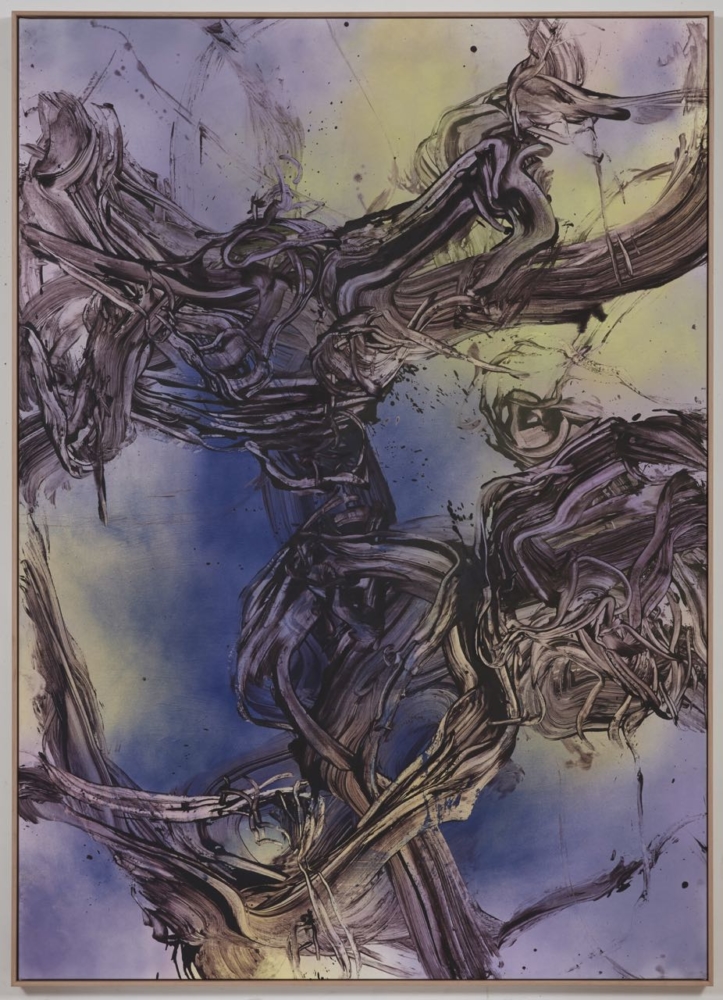

Millar’s painting may be perceived as abstract but she has long been interested in the depiction of three-dimensional space and the sense of scale. She is willing to take the abstract out of abstraction and to infuse her paintings with a sense of three-dimensionality. Her distinctive brush strokes are overlaid with sweeps of paint that flow and halt and turn in all directions to create richly suggestive forms. The large, painted surface of this work has a rich luminosity; it catches the light and gleams. Untitled playfully presents itself with the grandeur of her vision: a bold exploration of the colours blue and purple suggesting monumentality and materiality. Millar is acutely aware of this dramatic effect, noting that: “The joy and charm of painting for me is the illusion and virtual space it sets up… a completely dismantled kind of shimmering, hovering one”². Mary-Louise Browne – 2018

¹ Millar is quoted by Virginia Were, Art News, Autumn 2009, prior to her participation in the 2009 Venice Biennale. ² Millar is quoted by curator Justin Paton in I is she as you to me, 2003.

By Andrew Paul Wood.

Originally published on Eye Contact.

19th April 2018.

“A gesture cannot be regarded as the expression of an individual, as his [sic] creation (because no individual is capable of creating a fully original gesture, belonging to nobody else), nor can it even be regarded as that person’s instrument; on the contrary, it is gestures that use us as their instruments, as their bearers and incarnations.” – Milan Kundera, Immortality (1990)

‘Gesture’ and ‘gestural’ are vastly overused words in talking about abstract painting but remain unavoidable in talking about Judy Millar’s work. As Kundera intimates above, perhaps gestures perform us, rather than the other way around, memes proliferating like living things. Perhaps art is merely a long war to determine who is in charge. In Millar’s case, the resulting paintings are static and compressed records of the passage of time, modes of movement, the artist’s endurance, her physicality and physical limits—a record of metadata about the artist and the artistic act, its Benjaminian ‘aura of authenticity’. There is something profoundly human and humanist in this haecceity or ‘thisness’ of the artist, particularly the physical reality of the mark making in a world increasingly saturated with digital media.

This is very much evident in her show Welcome to the Fluorescence at Nadene Milne Gallery in Christchurch. There are just three big paintings in the main gallery space—and that is precisely enough in equilibrium with the space. The titles, Energy Trap, Waves Without Shape, A World Not of Things, are cautiously non-committal, setting up the audience with ambiguous hints at quantum mechanics and Zen ontology and letting them get on with the business of interacting with the work. The paintings activate each other. A World Not of Things might almost be toying with Chinese scroll painting—the palette and confident, but contained, calligraphic line—or a slightly Rococo interpretation thereof. The human tendency to pareidolia, finding order and shape where there is none, invokes everything from tangled tree branches and roots, to the Vatican’s Laocoön, but really it’s all about mind-mapping emotional and physical energy flows in moments of time.

‘Energy’ however, sounds like New Age handwavium. There is the physical energy of movement, of course, but might be better to call it thumos (θυμός)—passion, spiritedness, the internal urge for recognition, righteous rage against the injustices of the world, that which motivates human beings to exist. Peter Sloterdijk in his 2006 Rage and Time suggests that a productive, resentment-free form of ‘rage’ (which he, perhaps incorrectly, equates with thumos) is the primary motivating force of human social development, which Christian morality and psychoanalysis have attempted to supress (some might also include the contemporary politics of social discourse). This leads us to Mannerism.

Millar consciously aligns herself with the Mannerists, that oft maligned tendency in art that bridges the High Renaissance and the Baroque. The style is characterised by affected exaggeration and unnatural elegance in pursuit of effect. The standard art-historical view of how Mannerism came about tends to be that the followers of Michelangelo copied his dramatic and individual innovations, and their students copied them, and the resulting transcription errors resulted in flourishing mutations like Parmigianino’scameleopardine Madonna with the Long Neck (1534-40), the porcelain complexions of Bronzino’s Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (ca.1544-45), and Pontormo’s boneless, gravity-defying Depozisione (1528).

This is, in fact, not a subtle aspect of Millar’s work. The calculatedly optical effects of her palette and what looks like airbrushing declare open allegiance with the taffeta-like gradated colours of Pontormo’s draperies and garments. The open-ended, asymmetrical and complex Hans Hofmann-esque push-pull, and weaving in and out, of the bravura strokes—swept, painted and scraped back with a number of tools, including a plastic bag full of sand—conjure up impressions of the compositions of Parmigiano, Bronzino and El Greco as filtered through a century of transcendental abstraction.

An alternate interpretation of Mannerism, re-assessed against the political, intellectual and social crises of the twentieth century, was put forward by Italian critic and art historian Achille Bonito Oliva in his book The Ideology of the Traitor: Art, Manner and Mannerism, first published in 1979. Oliva reframes Mannerism as a subversive stylistic armour, tinged with hopeless melancholy, against the chaos of war and religious schism when it seemed the ideals of the Renaissance had failed and fallen. The artist, particularly the gay artist without benefit of the social transcendence of classical idealism, was identified as a traitor against their broader community, so why not make something of it? Bonito Olivia has elsewhere drawn parallels with postmodernism, and Susan Sontag intuited as much in her ‘Notes on Camp.’

While I wouldn’t call Millar’s work ‘camp’ per se, she observes that we live in “Mannerist times” (Trump, orange and coiffed, being la Maniera par excellence). The bravura gesture, the outrageous fluorescent palette, the occasional insouciant hand or footprint (Millar works on the ground) cock a snook at a Western civilisation apparently intent on self-immolating itself with as much dignity as it can muster. At the same time Millar very deliberately aligns herself with the grand tradition, albeit on her own terms—as something quite daring when that might be considered a liability in this sensitive age.

The antipole to Millar’s mannerism would be the Rococo—an equally fitting style for the present era, when the 1% squandered their wealth and resources on superficiality and frivolity, a style which also prioritises sinuous line and asymmetry. Even then the artists were getting their own back in silent protest—the wistful melancholy of Watteau, the brittle fragility of Fragonard—and if Millar ever ventures into a palette of silver, grey and faded rose, it would not shock me in the least. – Andrew Paul Wood.

Original article here.

13 April – 4 May 2018

Much of Judy Millar’s work is rooted in a childhood hunch. The young Millar intuited an elusive ‘something’ concealed behind the facade of the material world – a somewhat precocious permeation of the regular monster in the closet complex, with a universe-sized closet and metaphysics lurking in lieu of a monster. Most kids get over this sort of thing, but the distinct sense of something beyond our senses mystifies and intrigues Millar to this day.

In tandem with this playful metaphysical paranoia, Millar has maintained a longstanding commitment to the process of painting. Her oeuvre looks less like a collection of thoughts and paintings than a montage of thinking and painting in action.

Within her practice, constant artistic experimentation and mystic inquisitiveness engage and invigorate each other, together forming the engine of her creative evolution.

Perpetually refining her approach to art making in open defiance of inertia, Millar’s lifetime of innovations and insights has lifted her practice beyond New Zealand’s borders and into the international sphere.

As one might expect from an artist investigating the ambiguous nature of experience, Millar eschews direct symbolism in favour of allusion and impression. Her paintings, unimpeded by figuration and singular notions of meaning, deploy a kind of psychedelic abstract-expressionism in service of philosophical and aesthetic play. Blank canvases are transformed by the application and erasure of paint into writhing gestural labyrinths of form, torsion and colour.

One is left with the singular impression that Piranesi has returned from the dead, imbibed illegal substances, and tried his hand at contemporary abstraction.

Digitised brush strokes loop impossibly, penetrating amorphous clouds of luminous colour; here space is treated like paper in the service of origami: flipped and folded, turned inside-out, played with. Our tacit acceptance of the solidity and reality of things is upended and the universe is delivered from our comprehension into mystery. It’s quite good fun. Her work, in a delicious contradiction, is ludic to the point of seriousness – navigating portentous philosophical and aesthetic territory in a bewitching state of frolic. One can’t help but detect the notes of her joy in these meditations on painterly process and metaphysics – a joy so often in absentia in the discourse on such topics.

These elements are conspicuous in a practice that operates in an increasingly diverse array of mediums. Whether she’s charming children with a pulley-operated, large-scale fold-up-book (replete with projected visuals), crashing immense waves of canvas against the rigid ornamentation of baroque church architecture or erecting monumental sculpture that tumbles from the heavens, Millar invokes the invisible subtext underlying the appearance of reality.

Oscillating between her off the grid residence in NZ and her home in the Metropolis of Berlin, she continues her investigations of appearance and reality, poking with her paintbrush, year after year, at the beguiling veil.

Essay by Tracey Clement.

Painting is indexical; the marks on the canvas bear a direct relationship to the gestures of the artist. This is more overt in Pollock’s flung arcs of paint than in the minute daubings of a photorealist, but all paintings are a record of a body moving through space. The paintings in New Zealander Judy Millar’s solo show, My Body Pressed at Sullivan + Strumpf, have a particularly visceral quality.

- Judy Millar from My body Pressed, Sullivan + Strumpf solo show. 2018

- Judy Millar from My body Pressed, Sullivan + Strumpf solo show. 2018

- Judy Millar from My body Pressed, Sullivan + Strumpf solo show. 2018

- Judy Millar from My body Pressed, Sullivan + Strumpf solo show. 2018

- Judy Millar from My body Pressed, Sullivan + Strumpf solo show. 2018

Resembling tangled twists of muscle and tendons, Millar’s dynamic swathes of black seem to move at speed. “Like dance, painting is a direct record of the energy and feeling of a lived-in body,” says Millar, “and my work accentuates this.” Indeed, looking at her paintings is like witnessing the ghostly trace of the artist’s frenetic performance.

In this way, Millar’s abstract canvases are a kind of self-portraiture, but her work sidesteps objectification of the female body, a perennial trope in the Western canon. “Since the movements and actions of my body are stamped all over the canvas my work can be seen to be a picturing of the female body,” she explains. “But of course I’m not working with the body as an object. Rather I take the body as a process, something that can’t be contained. I want the work to be sexy in a fluid way.”

Millar’s title, My Body Pressed, expresses her concern that we are becoming disconnected from our bodies. “The increasingly mediated world we inhabit seems to be pulling our minds and bodies further apart all the time,” she says.

“I worry that our bodily world is disappearing, our bodily intelligence ignored. The title is a rallying cry to bodily communication: to the wonder of touch and sinew.”

Full article here.

The Sinew of Space

It’s frustrating to her, Judy Millar tells me from the West Coast of Auckland as we discuss her exhibition in Zurich, Swallowed in Space, that people are so rarely asking ‘what does painting do to us?’. An affective painting, after all, is something we want to go and see, and revisit, and make part of our wider experience. I wholeheartedly agree with her, especially after having just travelled to see her work (from my current home in Luxembourg) and encountering the way it not only activates space but also allows the kind of ‘space creation’ current in philosophy, cultural geography and advanced architectural research.

Engrossed in the exhibition’s spatial effect, I begin to realise that I am naturally embodying the paintings’ own quest for, and questioning of, modes of movement. Each painting is an intense material object based on movement, while it is also a container that circulates and throws me more broadly into an exploration of the space that emanates from it. ‘Space’ here, is a body-dwelt ‘imaginal’ field. It is the field projected from the body into a ‘spacious view’ of the ‘increasing inclusiveness’ of its expanding boundaries, as philosopher Edward Casey writes of place that has become more spacious in Western thought. In this kind of space, Casey writes, ‘expanding envelopments’ are all linked by the organic body and its history in the ‘fuller compass’ of what is happening, and at stake, in and from a particular place.

Essential to my experience, is the fact that each painting’s sinuous forms continue in striated bands that curve, twist, turn and loop seemingly without end. As I follow them, they always release their coiled directions onwards, even if only through a series of drips, a finger drag or the suggestion of an aspirating colour. They are not brushstrokes, but rather a skilfully indeterminate ‘caricature,’ or parody, of such a singular gesture. Their banding is almost collographic in nature: a result of the artist’s characteristic mark making that accumulates the positive and negative impressions of paint in the push and drag of objects across the painting’s surface. ‘I was trying to think of something like a very big fingertip,’ the artist tells me as she describes the way in which she slid differently-sized bags filled with sand through the paint. They allowed complex forms of movement, she explains, ‘and they have this particular feeling.’ For me, their form is fibrous, elemental and constant, like bands of tendon, muscle fibres, the phloem tissue of bark, and the cellulose cordage of plants. They seem to hold painting and movement together. – Excerpt from the article written by Jodie Dalgleish.

View original publication.

January 25th – February 17th 2018

Photos courtesy of Robert Heald Gallery.

26 October – December 2017

Blood red, jade green, and a bruising purple resonate against yellow and incandescent orange in Judy Millar’s new paintings.

The colour palate is double-edged: reminding us of the moments when nature thrills us with sunsets, sunrises and deep blue lagoons but also recalling the colours of comic books and their depictions of outer-space adventure and future doom.

Millar, a fan of popular science, describes the activity of painting as a form of space travel. When painting Millar experiences space and time merging. As the title of the show suggests, during this process she feels “swallowed in space”.

In this new group of works form becomes the graph of activity. The appearance of “things” emerges from the web of painted lines and fields of colour. Things hard to name but fleetingly apparent establish a semi-believable pictorial space. These strangely spatial paintings exude an otherworldly luminosity as if emitting light from a distant time and place. As Millar applies then removes layers of paint from the surface of the works she seems to release energy as if an image has been held in matter and is now freed into visibility.

Full exhibition history here.

July 2017 – July 2019.

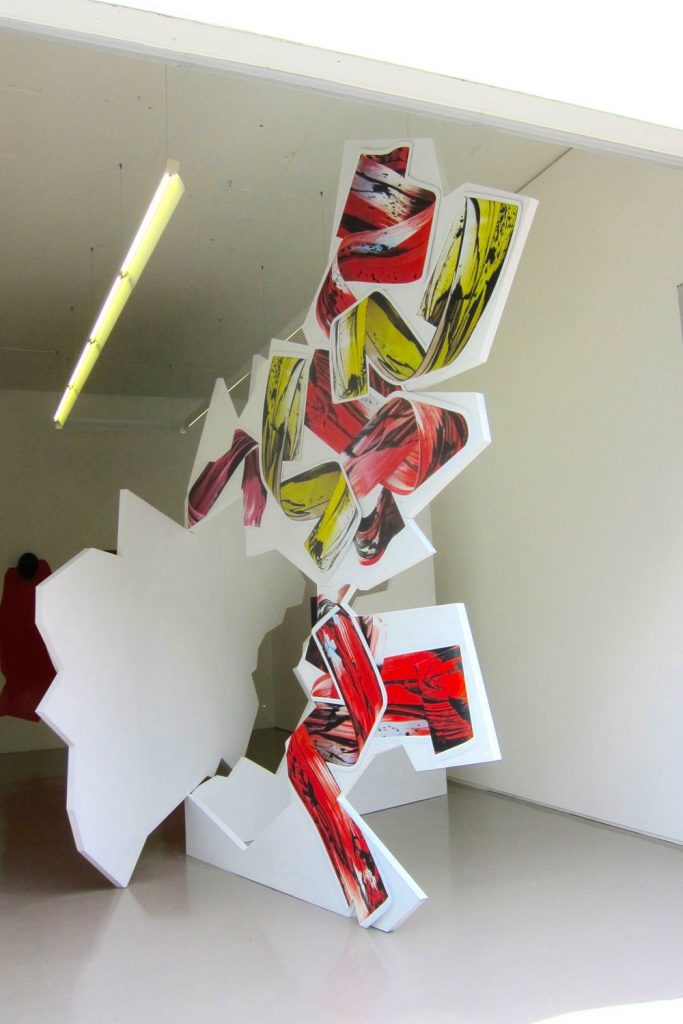

In the South Atrium of the Auckland Art Gallery resides my latest major site-specific commission, Rock Drop 2017. Acquired by Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki with the support of Auckland Sculpture Trust, Auckland Contemporary Arts Trust and Auckland Art Gallery Foundation’s 2016 annual appeal.

“This work plays with the complexity of the vibrant junction between the Victorian, neo-Classical and 21st century architecture of the building, Millar’s towering painterly installation responds to the dynamics of the space and appears to change and morph from different perspectives, provoking new and exciting experiences for Gallery visitors.” – Curator and Gallery Director, Rhana Devenport. 2017

30th August – 24th September 2016

Image: Judy Millar, Advancing All Electric, 2016. Installation view, Galerie Mark Müller, Zurich. Photo: Millar Studio. Courtesy the artist.

Merzbau explored new spatial ideas in art, and my work also relates to new kinds of space, specifically combining elements of architecture, sculpture and painting. I am also interested in the idea of collage that Schwitters was using. Of course, he was collaging everyday material, and I am reassembling digital reproductions of my own painted images. The worthwhile thing about showing in Europe is that you get these very new takes on the work that you are doing—connections that wouldn’t be immediately made here, in New Zealand.

Image: Judy Millar, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic and oil on paper, 89 x 64 cm (incl frame). Courtesy of Bartley + Company Art.

They are called ‘space works’. In the studio we call them ‘props’ rather than sculptures. I would always bristle when the people I work with in the studio called them ‘sculptures’. So we came to the decision that we would call them props—I quite like the word.

Yes, they are a spatial collage in this respect, so this does fit quite well with the Merzbau concerns. On the surface of the structure, I am placing images of other forms that I’ve made in three-dimensions then photographed and had printed onto sticker paper. So the main space work has images of other spatial works hanging on its surface. These images really are like big stickers on the surface of the work. Each of these stickers is stuck to a piece of thin aluminium that is then gently curved in different directions. The difference with this new work is that the stickers, instead of being flat on the surface like previous works, curl away, gently lifting away from the form itself.

So it is quite a complex piece that involves both illusionistic curves and physical curves—real shadows and images containing shadows. If anything, these works are lampooning big heavy ‘male’ sculpture. It is a very gentle dig. These are stickers! It is everything that you shouldn’t do with a traditional sculpture: it’s illusionistic, it’s not real, it’s plywood made to look like cardboard, and it carries images on its surface.

Image: Judy Millar, Advancing All Electric, 2016. Installation view, Galerie Mark Müller, Zurich. Photo: Millar Studio. Courtesy the artist.