Judy Millar is interviewed by Graeme Douglas

I used to think painting was a way of thinking. Now I know it to be much more than that.

It is the flash of big brain meeting small brain, of consciousness meeting thought, or of consciousness meeting mind through the body.

Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand presents A World Not Of Things, a solo exhibition of new paintings by Judy Millar. 17th April – 4th May 2019

Art Collector Australia interviews Judy Millar about her work in 2019’s Art Basel. Specifically in connection to the late New Zealand painter Colin McCahon’s legacy and his practice in relation to his International contemporaries.

Bob Chaundy catches up with Judy Millar on the first evening of her first London Solo show.

Robert Leonard talks to Judy Millar. The interview discusses her work in Personal Structures, Venice, 2010.

17th April – 11 May 2019

Judy Millar, March 2019

I was sitting down to write up notes about this exhibition on March 15th when headlines wrote themselves across my screen. A man and a gun had vented rage and hate against fellow New Zealanders in their time of prayer.

Times like this make you question a life in art, a life that is in itself a kind of devotion. It can seem to lack the necessary force to counter-strike. It can seem too invisible as an influence on everyday life.

The seeming inadequacies of art became even starker when I began to view this desperate act of violence as part of a broader picture appearing around the world. We have long lived in a world that has assumed white superiority but it is fast ramping up, in so many parts of the world, into an outright declaration of supremacy.

We are living in a time where democracy itself seems challenged if not directly threatened. We have reached a point where we make enemies of those who hold different political perspectives than our own. We live in a time where we ‘unfriend’ those who challenge or criticise us. Where we object to listening to opinions we don’t already fully agree with and where we respond with outrage to views that clash with our own. All of these attitudes and behaviours run counter to the core democratic principle of respect for differing opinions.

I have always believed that involvement in art is primarily about absorbing different points of view. Being open to art is about gaining the flexibility to look at things from all sides and in doing so to nourish our empathic humanity. But on March 15th I once again had to ask – is this enough?

I still don’t have an answer to that question but while thinking deeply on this over the ensuing days I stumbled on this quote from Simone Weill. In her Notebooks she writes that we are helped by meditating on “absurdities which project light”.

For now this definition seems a suitable definition for art, and one that can give me some hope as to art’s ongoing importance. At the very least I will take it as a definition of my own project.

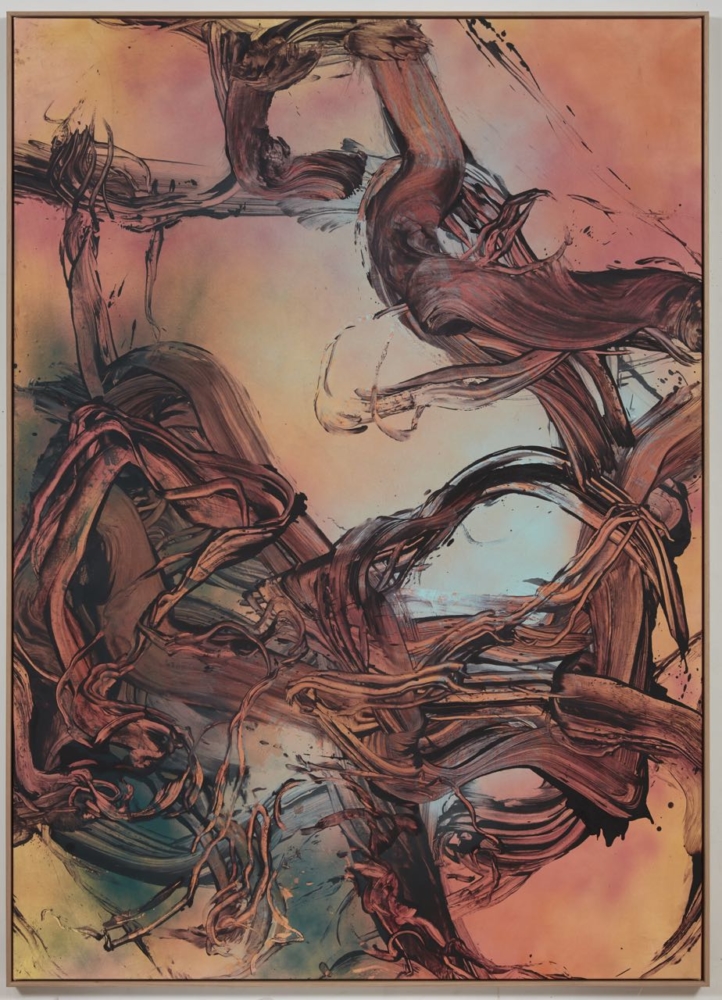

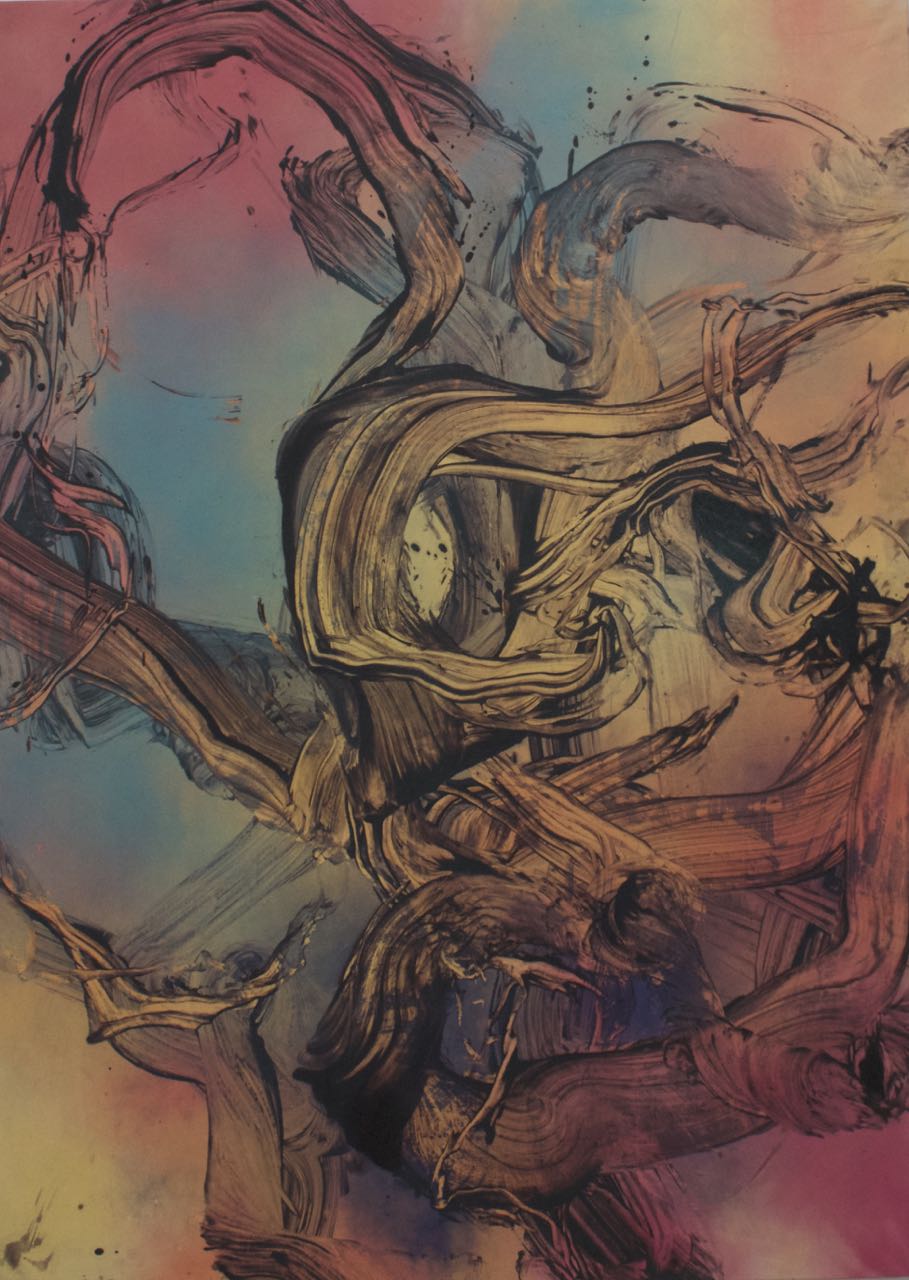

I have worked hard to light these canvasses from the inside out. I have sought to combine the paradoxes of coloured earth and a suggestion of the immaterial. I have desired a feeling of space and surface coexisting. I have tried to evoke dusk – the time of day that is neither day nor night but is both at the same time. I have wanted to suggest a multitude of things and nothing at all.

I know this is not enough, but for the interim it is what I can offer. I hope that it will encourage contrasting viewpoints. In doing so it might enable the widening of our individual perspectives.

“The gestural and abstracted surfaces of Judy Millar’s art are both intensely physical and highly mediated structures, reflecting the paradox we face of inhabiting both corporeal and cognitive realms.

Millar, a distinguished and internationally acclaimed artist, employs the processes of erasure – wiping and scraping paint off the surface of the work – to create visceral canvasses that invoke a sense of the body.”

art_messenger 2019

For Art Basel Hong Kong 2019, Gow Langsford Gallery presents a selection of work that demonstrates the late New Zealand painter Colin McCahon’s legacy and considers his practice in relation to his International contemporaries.

Can you tell me what you’ve been working on for the show?

I am showing new paintings, not exactly made with this show in mind but certainly indebted to McCahon. His oeuvre is so vast and rich that any painter working in New Zealand will find themselves conscious of his presence over and over again.

I recently finished reading Knausgard’s A Time for Everything in which he retells biblical stories, setting them in his homeland. I live on the Tasman seacoast not far from where McCahon painted most of his late works centred on religious texts. The mix of bible story, angels, Noah, coastlines, gannets and rising waters seems to have filled my imagination this summer.

“The telling of great stories set in your own backyard has lead me to seriously reconsider the importance of place. My own works have become increasingly infused with West Coast Auckland. The landscape is always there.”

How would you describe McCahon’s legacy within New Zealand art history?

McCahon was a visionary. He brought an ambition to his work that sought to match the great painters of history. Through his commitment, he laid the ground for art to become a serious undertaking in Aotearoa [New Zealand]. For it to matter, because it spoke directly to an experience of the country as it was. It was as if he banged a stake in the ground and stood by it.

You were the first artist to take up the McCahon House Artist in Residence programme in 2006, which saw you move into a purpose-built studio just next door to the bach [a New Zealand term for holiday house] where McCahon and his family lived in the 1950s. What did you take from this experience?

This time was a complete turning point for me. The bach where the McCahon family lived has been turned into a small museum containing his archived correspondence and tapes of him talking about various things. As a resident you get 24-hour access to the museum. I would go very often at night and sit and listen to Colin speaking. It was as if he was talking directly to me. Telling me to wise up, get serious. It came at the perfect time in my life. In that house you know that art matters.

How does the idea of legacy – of leaving something behind you that has the potential to influence future generations – play into your practice? Has this changed over time?

I’m an art history junky and love to see how things have influenced and do influence other things. But I have the feeling we are in a new world. Everything is on the table now and the pathways of influence will become largely untraceable in the future I think.

What would you say is the most important issue facing New Zealand artists working today?

I think the biggest issue is, as for everyone else, is sustainability. Artists working in New Zealand need to travel a lot and that’s going to be increasingly difficult to justify.

We are also suffering in New Zealand from an absence of genuine critique. Increasingly we are divided into smaller and smaller interest groups that make rigorous expansive discussion impossible; this is making it very difficult to develop complex artistic practices.

Published September 2019

Judy Millar’s work has seen many forms, including large paintings that tumble from the gallery ceilings in large coils. For her first solo show in London, The View from Nowhere, she presents six paintings full of energetic and colourful works that include a signature process in which she removes layers of paint from the surface after applying it. Bob Chaundry talked to Judy Millar on the first evening of her show.

How did you prepare for this show, your first solo show in London?

I work all the time and I try to choose good work that looks the right scale for the room. So I built myself a little model of the gallery and I worked with differently sized paintings that I thought would have an interesting relationship with the scale of the room.

You are quite known for your leviathan size works.

I work in a huge range of sizes, from very small to very, very large. Every work in a way has to have an interesting relationship to the body, so whether it’s a tiny scale or a big one. I think painting is like a portal and can suck a whole room into it if it’s working well. So that’s the kind of relationship I’m always looking for. I want a tension between the pictorial surface and the space it occupies.

I’ve read that you compare the act of painting to space travel.

Yes, that’s my experience when I’m working. I really feel that space and time dissolve into one another and I almost become non-existent. I suppose in contemporary terms it’s like disappearing down a black hole which is a very amazing feeling.

Is that what some would call getting into the zone?

I think athletes refer to it that way. It’s a different sort of consciousness, you step into an entirely new way of being.

My first reaction on seeing your paintings was that they’re very organic.

I think they’re both organic and highly synthetic. I’m always trying to bring the most contrary elements together in a work as possible. So, on one hand they’re very organic, on the other they’re highly artificial and synthetic. On the one hand they’re very free in their making, on the other hand they’re very constructed. I think painting at its best can bring these very paradoxical activities into one image.

Why do you feel the need to have these opposing forces together?

Because I feel that that’s what painting can do, and it’s something that very few of the other media can do and that comes from the fact that painting is both an illusion and a physical being at the same time. That’s very unique. A film is not. You can’t reach out and touch a film, it vanishes. A book is only able to be understood through a process of time. With a painting you get it all at once and you can relate to it as a physical thing while at the same time it’s highly illusionistic and a mental construct.

“I think being human, one of the dilemmas of our lives is that we live in these two realms, the mental realm and the physical realm and that causes us endless problems.”

So we have our imagination and our dreams and our fantasies and we have to deal with the reality of tables and chairs and cars and roads and all those other things. Humankind has always had to do that and I think religion attempts to bring those things together and I think art is another attempt to bring those things together to try to understand our dual existence. For me, painting can really hammer that dual existence, it can really deal with it.

So, where does your inspiration come from?

Through a long, long involvement with both looking at painting, thinking about painting and making painting and from my experiences in the visual world. And then it’s my very intimate relationship with the material I’m working with. So it’s all those things coming together.

Do any particular artists influence you?

Every day someone new. Every show I see, someone new. It’s extraordinary to see, as I did in the National Gallery this morning, paintings you know quite well and then you see new aspects to them.

I see colours that I think could be useful, the way artists have loosened the world up. When I look at a painting I ask myself what are they seeing. How are they trying to re-see that when they work? What have they seen, what are they seeing, and how are they presenting that are questions I’m always intrigued by.

How do you go about constructing your paintings?

It’s very traditional in many ways. I start with lighter colours and work towards darker colours. Then I’m pulling paint off the surface so it’s really a matter of putting paint on and taking it off until I arrive at something that I recognise in a way. So it’s a to-and-fro process of application and removal.

Why do you remove paint?

I started off painting in the 1980s and it was a time when deconstruction was the mode. I wanted to discover for myself what was the minimum a painting could be. So I started to remove stuff and I’ve always stayed with that. It’s a bit like a fashion designer’s work undoing clothes and finding how they could deconstruct a garment and I was trying to do the same with painting.

But do you know which bit you’re going to deconstruct before you do it?

At that time I was trying to understand how far I could deconstruct painting and I ended up with works that were just marking tape and gesso. Obviously I’ve become much more involved with image since then but there is still that aspect of putting things on and stripping it away in order to get at something that is just enough and vital.

“I saw a fantastic Francis Bacon show in Basel earlier this year and he said I want to get as close to the nervous system as possible and that really resonated with me because sometimes you want to get so close that you put your whole body in there.”

That’s when your hand will just go into the paint. You want it be as close as possible to your body. I work on the ground, it’s all very fluid. It’s quite physical, I need to use a lot of force. I walk into the works if they’re very big and paint my way out of them. I’m always finding new kinds of things to use to move the paint. I use rags and brushes and I use spray and tools that I invent and tools that I find and my fingers and feet and everything else. It’s a dirty business (laughs).

So beneath these layers of paint is a nervous system

When my hand is in the paint obviously the connection of the paint and my nervous system becomes one thing. The image becomes just the extension of the nervous system in a way.

Born in 1957, Judy Millar has become one of New Zealand’s best-known painters, representing her country at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009. Her work has been exhibited not only throughout her own country but also in Europe and the United States to much critical acclaim.

Source | More from Bob Chaundry

The View from Nowhere is showing at the Fold Gallery, 158 New Cavendish Street, London W1W 6YW until 20 October 2018.

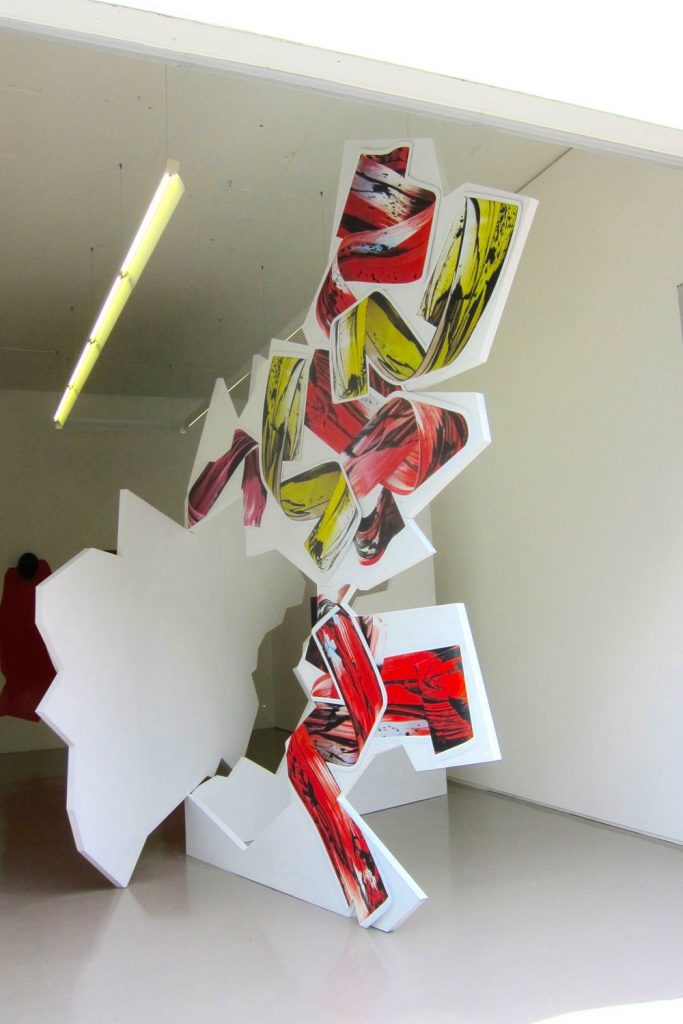

Image: Judy Millar, Advancing All Electric, 2016. Installation view, Galerie Mark Müller, Zurich. Photo: Millar Studio. Courtesy the artist.

Merzbau explored new spatial ideas in art, and my work also relates to new kinds of space, specifically combining elements of architecture, sculpture and painting. I am also interested in the idea of collage that Schwitters was using. Of course, he was collaging everyday material, and I am reassembling digital reproductions of my own painted images. The worthwhile thing about showing in Europe is that you get these very new takes on the work that you are doing—connections that wouldn’t be immediately made here, in New Zealand.

Image: Judy Millar, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic and oil on paper, 89 x 64 cm (incl frame). Courtesy of Bartley + Company Art.

They are called ‘space works’. In the studio we call them ‘props’ rather than sculptures. I would always bristle when the people I work with in the studio called them ‘sculptures’. So we came to the decision that we would call them props—I quite like the word.

Yes, they are a spatial collage in this respect, so this does fit quite well with the Merzbau concerns. On the surface of the structure, I am placing images of other forms that I’ve made in three-dimensions then photographed and had printed onto sticker paper. So the main space work has images of other spatial works hanging on its surface. These images really are like big stickers on the surface of the work. Each of these stickers is stuck to a piece of thin aluminium that is then gently curved in different directions. The difference with this new work is that the stickers, instead of being flat on the surface like previous works, curl away, gently lifting away from the form itself.

So it is quite a complex piece that involves both illusionistic curves and physical curves—real shadows and images containing shadows. If anything, these works are lampooning big heavy ‘male’ sculpture. It is a very gentle dig. These are stickers! It is everything that you shouldn’t do with a traditional sculpture: it’s illusionistic, it’s not real, it’s plywood made to look like cardboard, and it carries images on its surface.

Image: Judy Millar, Advancing All Electric, 2016. Installation view, Galerie Mark Müller, Zurich. Photo: Millar Studio. Courtesy the artist.

I try and undo them because I want to understand them. My way of understanding something is to pull it apart. A good sculpture is about a form in the round that both alters and is altered by the space that surrounds it. But I am more interested in it existing as an image rather than a form. This recent spatial work is primarily made up of slotted planes—it is planar in the sense that it is really just an image surface that has become a little more complicated.

Image: Judy Millar, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic and oil on paper, 115.5 x 86 cm (incl frame). Courtesy of Bartley + Company Art.

Yes, an absolutely central interest of mine is how a painting alters its spatial environment. On one level, the painted works are a ‘finding out’ process that includes some really basic stuff about how colours interact and how the very fluid and incredible medium of paint functions. But I am painting these works flat on the floor and when I am doing this, I am trying to build an entire space. It is not that I am just thinking of a two-dimensional planar surface on the ground. It is as though I am trying to build a dome-like space above the canvas. I am in space; my movements are in space. So the painting is really about creating a form of space. It almost lands on that plane with the hope that, when I put the canvas upright, it is going to then come into the viewer’s space—that it is going to determine this space or influence it in someway.

The word that always sets my teeth on edge is ‘gesture.’ Gesture seems like something that comes gushing out from deep inside you. That is not really what I am interested in. My work is much more about drawing; it is about looking and seeing, less about ‘expressing’. I’m using gesture only in the sense that a gesture can communicate something.

But Abstract Expressionism did produce some pretty amazing work and it also fell into a very big hole. I think there is something in there that is still worth exploring—that is still worth bringing forward. But like everything that is continually repeated, Action Painting became nothing but a mannerism. And I am very aware that I am referencing this form of painting in a ‘gone’ way. I am not really parodying it; rather I am referencing a ‘gone form’. It is a form that already stands for something. This continues to interest me greatly with painting. — Read original article here.

Judy Millar: For this exhibition, I’ve been given a small room with two beautiful windows, which open out onto a canal. I’m making a twosided painting that forms a big springy strip. The room is about 6m long but the painting is 20m long. Since the painting is too big for the space, there’ll be a tussle. The painting will be forced to lift itself up into the air, go out of the window, and come back in. It’ll double back on itself and loop around. It’ll be delicate but cumbersome, a physical gesture in real space but also a bearer of illusionistic painterly space.

Robert Leonard: You’ve been blowing up “the brushstroke” for a while now.

JM: It started with Giraffe-Bottle-Gun, my 2009 Venice Biennale show. I made small paintings, then enlarged the imagery to ten times the size. I used a billboard printer—an advertising tool—to do it. I wanted the work to advertise itself. I wanted to amplify everything.

RL: But the new work is painted, right?

JM: The orange bits are painted but the black bits are printed. Both have been up-scaled, but to different degrees and in different ways. I’ve been developing big brushes with multiple heads so that I can make giant gestures. I’m trying to find a bigger dimension for myself.

RL: With the up-scaling and the use of printing, are you trying to denature or dehumanise the brushstroke?

JM: I’m not trying to dehumanise it, if anything I’m trying to rehuman ise it. I’m trying to give it more authority. Despite the absurd scale, you still read the work through your body.

RL: In this work, your painterly marks piggyback on a support that is itself akin to a painterly mark–a flourish.

JM: Exactly, it’s gesture in real space that carries other gestures on its surface. The illusionistic surface distorts your sense of the real physical form, and vice versa. By manipulating the support structure itself, I’m dismantling the usual image/support hierarchy.

RL: I’m reminded of the plastic toy-car track that I had as a child. I would bend it into curves and loops and send my cars careering down it. Your support will operate as a track for vision.

JM: The eye is forced to follow the track. I can control the eye; slow it down on the curves and speed it up on the flat. Space will turn into time, and time into space. What was behind will suddenly be in front, edges will become lines and lines will become edges— everything will be turned inside-out.

RL: Because they are so antithetical, I was reminded of Lynda Benglis’s paint pours from the late 1960s. She let paint fall from the can onto the floor, whereas your piece is perky, springy, alert. It isn’t paintdoing- what-comes-naturally.

JM: I’ve never been one of those materialists who think paint is more interesting in the can. For me, painting is not about paint, or even about paint on a support. For me, it is about structures: illusionistic structures, logical structures, worldly structures, all sorts of structures. I’m not interested in paint simply as a material.

RL: So why paint?

JM: I stay interested in painting: it’s a way of collapsing the separation of the mental and the bodily that I experience in so many other parts of life.

RL: So, you’re affirming rather than critiquing painting.

JM: I’m questioning and hopeful. I’m asking what can painting still say, and hopeful that it can still say something.

_

Robert Leonard is Director of the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane.

New York, 2010

Image from uploadvr.com

Excerpt by Gemma Gracewood about a day spent with Judy.

Judy Millar’s MoMA artist’s pass is looking battered. “I’ve been at least twenty times since I got here,” she admits as we enter New York’s Museum of Modern Art. She pays for me – “I got my studio deposit back today. I feel rich.”

Judy is one of the more interesting characters on our art scene. Or, not on our art scene. She flies under the radar by living way out west of Auckland, yet she exhibits all over the world and keeps a studio in Berlin.

One of New Zealand’s foremost painters, Judy was one of our gals at the 2009 Venice Biennale. (For NZ folk, her Giraffe-Bottle-Gun work has been remounted at Te Papa for a spell.) I worked with her on the wonderfully bonkers TV series New Artland. In it, she guided a group of teenagers towards making an audaciously messy group painting, then turned into a giant billboard using a digital process similar to the one she went on to make her Venice work with.