The Future and the Past Perfect

Judy Millar im Kunstmuseum St Gallen

REVIEW

- März 2019 • Text von Benita Böhm

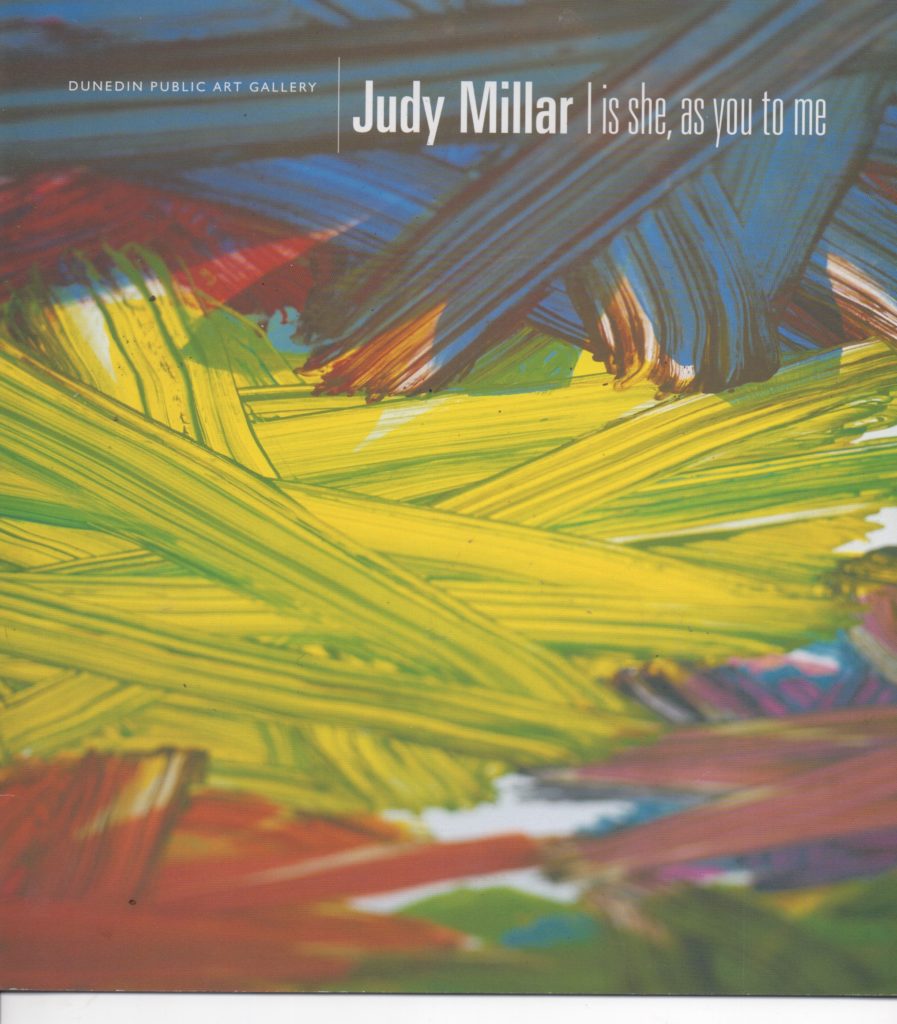

Judy Millar arbeitet sich an der Malerei ab, zerlegt die Geschichte und die Techniken des Mediums. Damit wurde sie zur wohl bekanntesten Künstlerin Neuseelands. Das Kunstmuseum St. Gallen widmet ihr nun die erste große Einzelausstellung außerhalb ihres Heimatlandes.

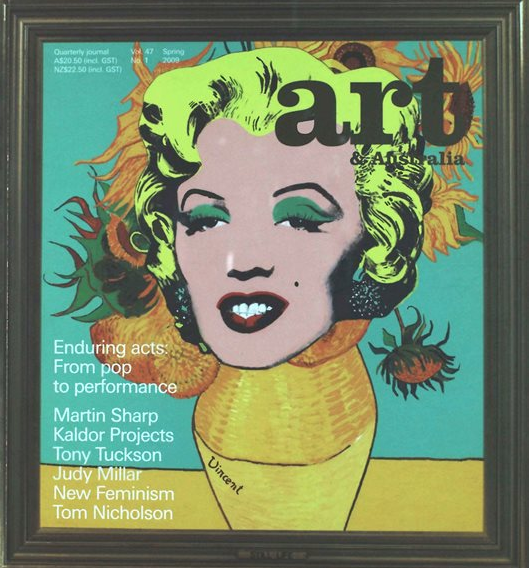

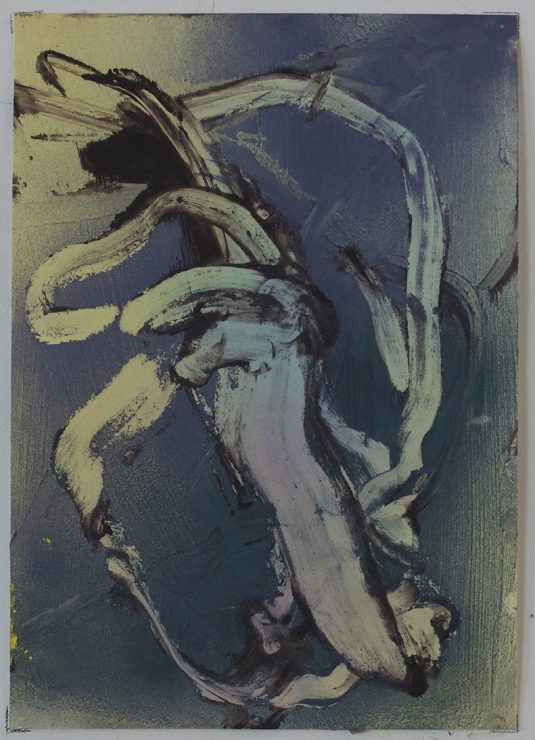

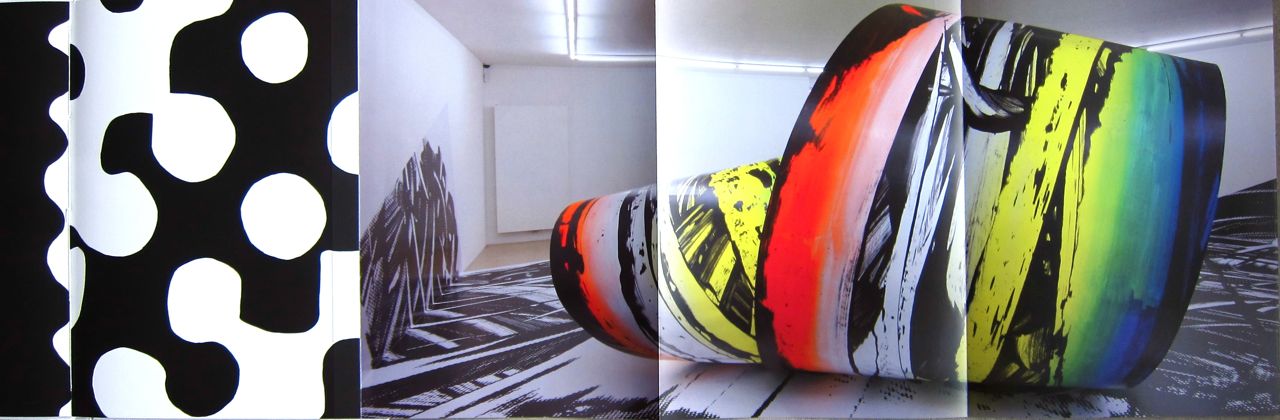

Judy Millar, Don’t Call Me Baby, Baby, 2002, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Nach eigener Aussage geht es Judy Millar darum, ihren Platz in einem Genre zu finden, das für sie in ihrer persönlichen und künstlerischen Entwicklung keine Vorbilder bereithielt. Der Blick zurück in die Kunstgeschichte der Malerei war für sie primär europäisch und männlich geprägt. Als neuseeländische weibliche Künstlerin hinterfragt sie diesen Kanon distanziert, dekonstruiert ihn bis ins Detail und entwickelt dadurch einen eigenen unverwechselbaren Stil.

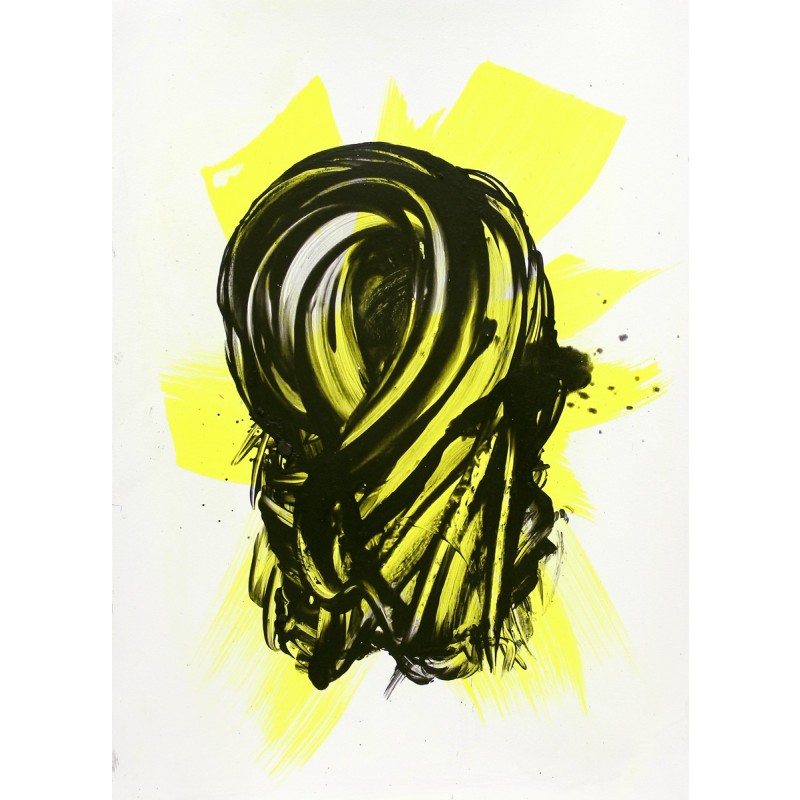

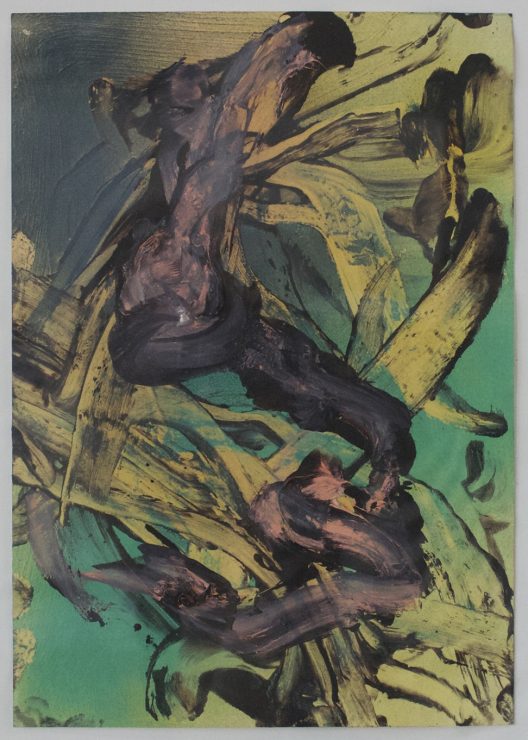

Judy Millar, Untitled 2005, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

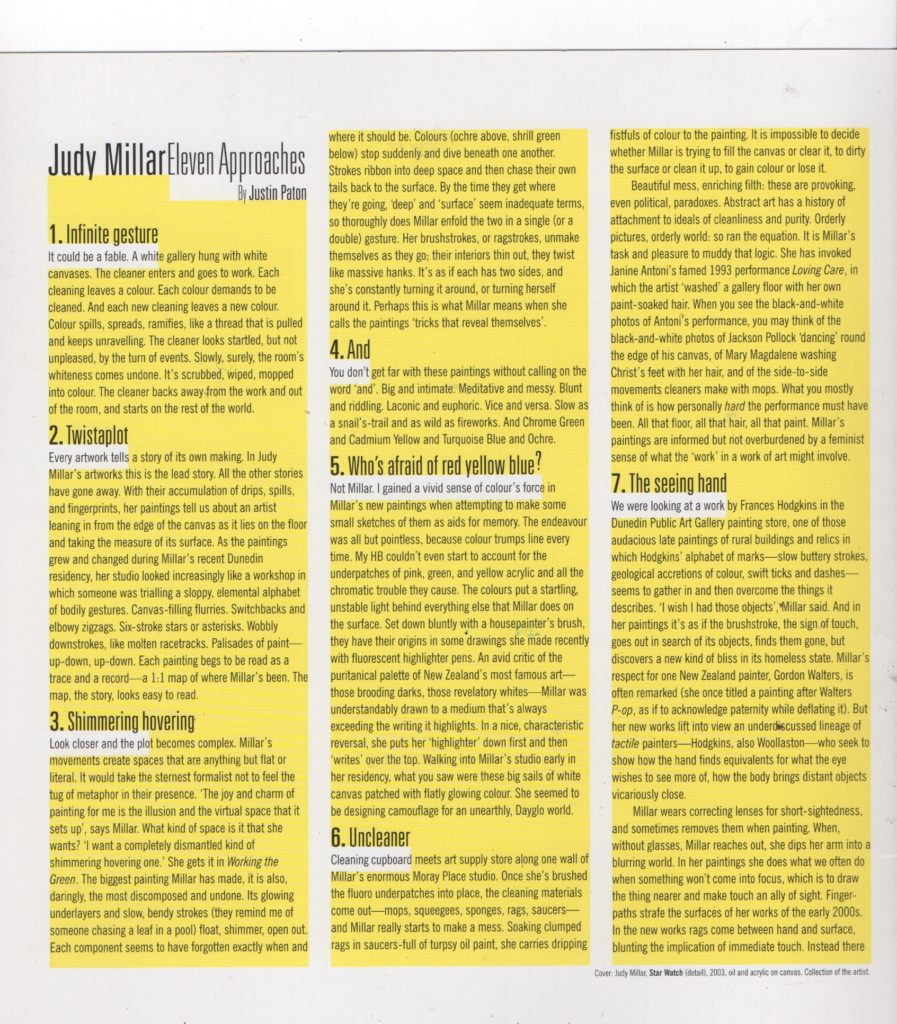

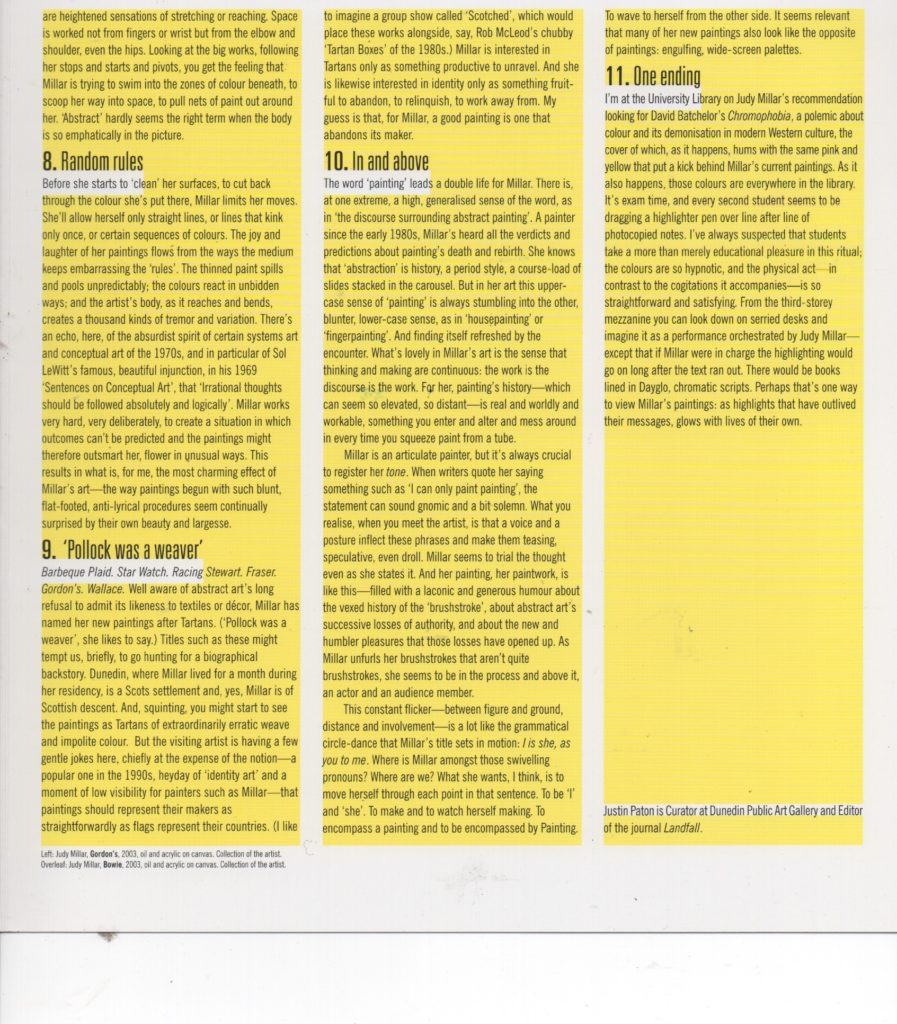

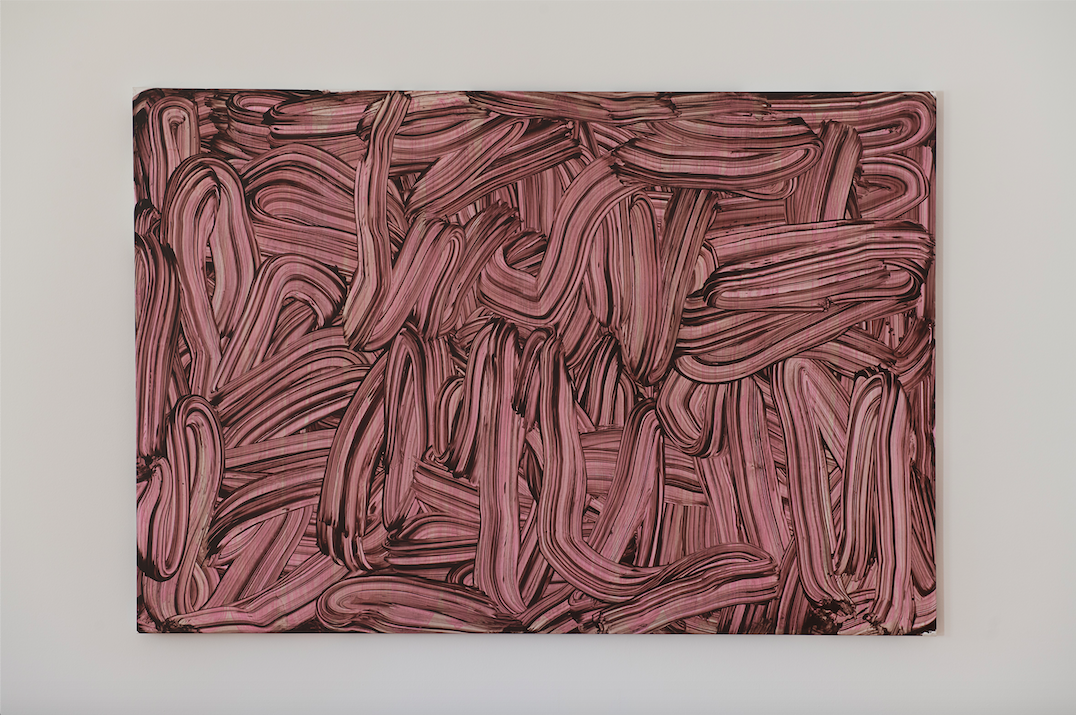

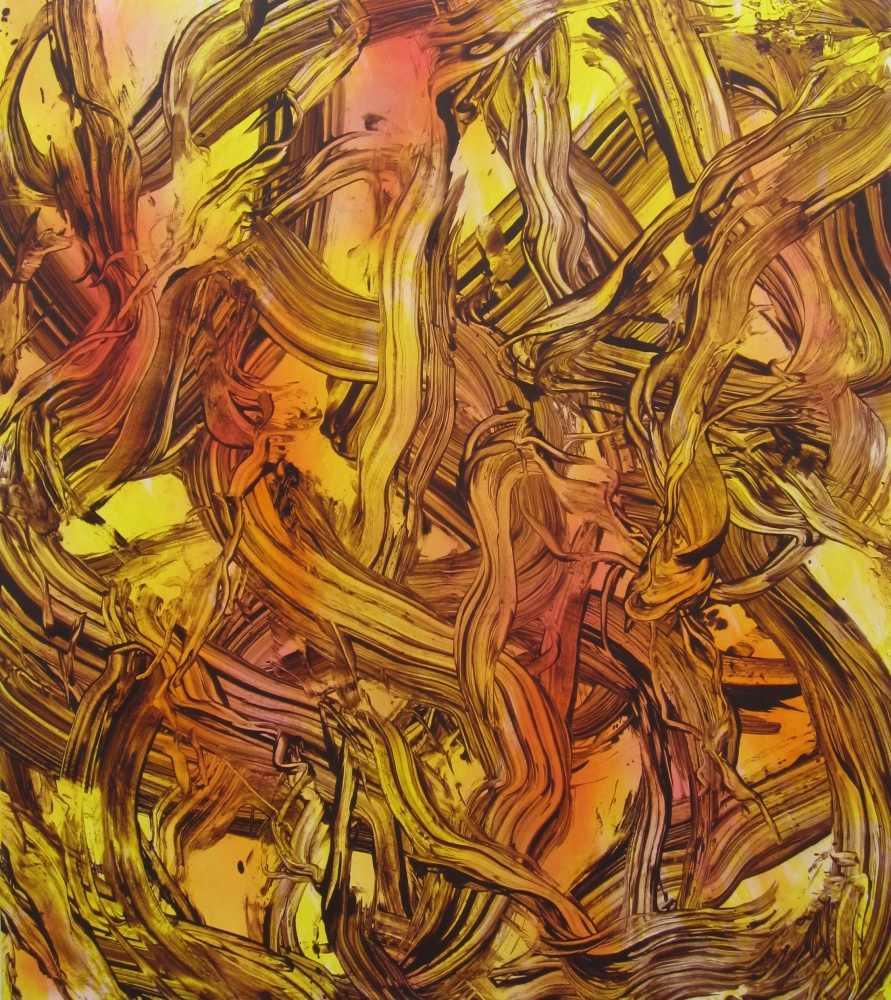

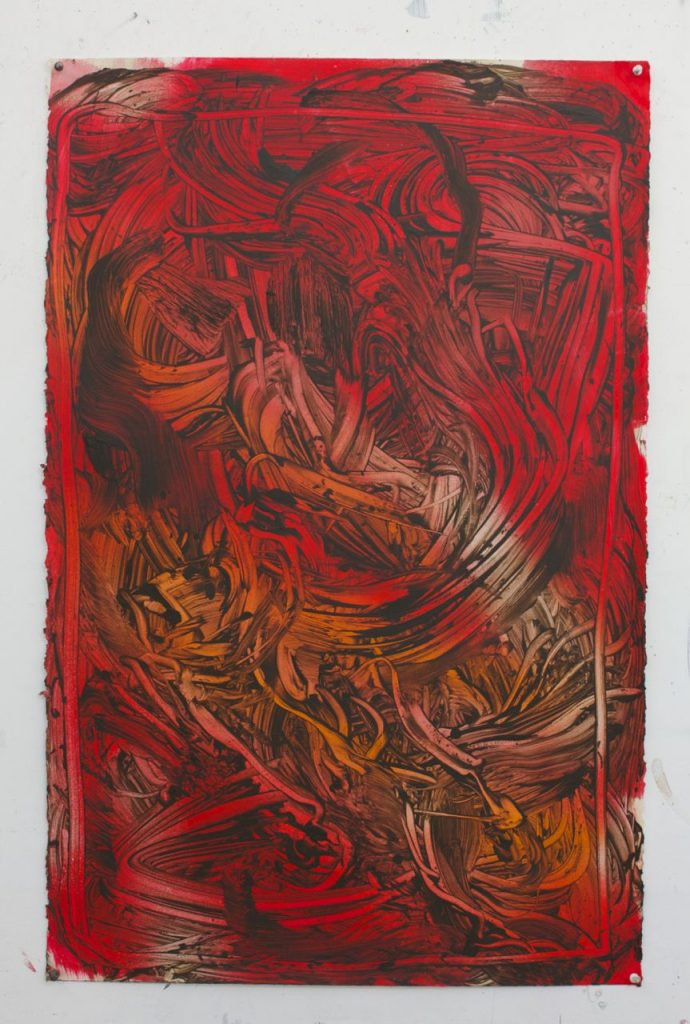

Dies zeigt sich bereits an der für sie typischen und sehr individuellen Arbeitsweise, die durch einen Prozess des Wegnehmens geprägt ist. Damit kehrt sie das grundlegende Prinzip der Malerei um: Aus dem additiven Auftragen von Farbe und Material wird ein nicht minder ausdrucksstarker Vorgang der Substraktion. Auf den ersten Blick erinnert der Duktus der Gemälde an intuitiv und dynamisch aufgetragene Pinselstriche. Tatsächlich trägt die Künstlerin Schichten von Ölfarbe auf die Leinwand auf und nimmt diese mit Stoffbahnen oder mit Sand gefüllten Plastiksäcken wieder von der Oberfläche ab. Dies sei − ganz anders als der erste Eindruck vermuten lässt − ein sehr langsamer und kompositorischer Vorgang körperlicher Anstrengung, erklärt Judy Millar. Und tatsächlich sind die in den Werken manifestierte physische Präsenz und der gestische Ausdruck unmittelbar für den Betrachter spürbar.

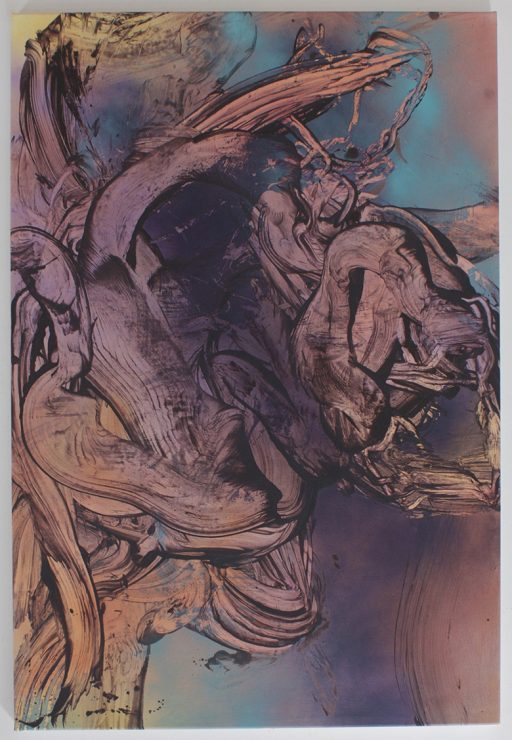

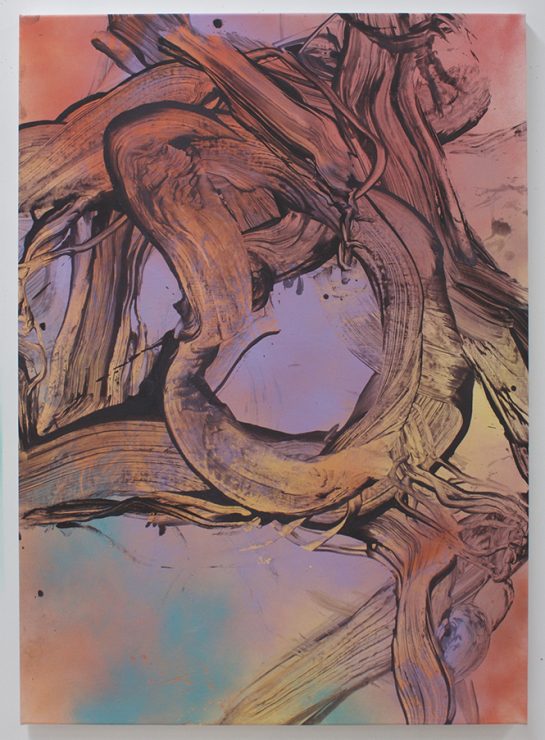

Millar pendelt zwischen Auckland und Berlin und identifiziert sich mit der aus der räumlichen und charakterbezogenen Distanz entstehenden Ambivalenz der beiden Orte. Zwischen der großflächigen Landschaft Neuseelands und dem dazu in Kontrast stehenden Leben in der Großstadt bildet sie ihre künstlerische Identität und zieht ihre Inspiration für neue Arbeiten. Die großformatig angelegten, raumgreifenden und extra anlässlich der Ausstellung „The Future and the Past Perfect“ in der Kunsthalle St. Gallen konzipierten Arbeiten „It to Them, to Us to I“ konnten somit nur im Kontext der neuseeländischen Weite entstehen.

Judy Millar, It to Them, to Us to I, 2018, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Dabei interessiert die Künstlerin auch das Spannungsverhältnis zwischen Malerei und Architektur. Die Werke sind bewusst überdimensional gestaltet und scheinen die mit Stuckelementen und Bordüren geschmückten Räume des Museums regelrecht zu sprengen. Gleichzeitig geht es Judy Millar dabei aber nicht um eine skulpturale Ebene von Malerei. Sie sieht ihre Arbeiten explizit als Gemälde an und will sie nicht als genreübergreifende Objekte verstanden wissen. Die Kunsterfahrung soll sich deshalb auf die frontale Betrachtung der eindimensionalen Leinwände beschränken. Ein allseitiges Begehen des Raumes, um einen Blick auf die Rückseite der Werke zu werfen, ist gerade nicht intendiert.

Bei Judy Millar geht es in vielerlei Hinsicht zunächst um die Herstellung von Referenzen durch Nachahmung, welche durch eine eigenständige Interpretation aufgebrochen werden. Besonders deutlich wird diese Herangehensweise an Millars Auseinandersetzung mit der Kunstgeschichte der Malerei. Es zeigt sich an der Optik perfekt durchgeführter Pinselstriche, die gar keine sind. Vor allem die jüngeren Werkserien scheinen besonders impulsiv kreiert, beruhen jedoch wie alle Arbeiten der Künstlerin auf einer bewussten Farbauswahl und Durchführung der einzelnen Arbeitsschritte. So wird der Betrachter immer wieder dazu veranlasst, seine eigene Wahrnehmung zu hinterfragen und einen neuen Zugang zur Malerei zu finden.

WANN: Die Einzelausstellung der Künstlerin mit dem Titel „The Future and the Past Perfect“ ist noch bis zum 19. Mai zu sehen.

WO: Im Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, Museumstrasse 32 in 9000 St.Gallen.

Diese Review entstand in freundlicher Zusammenarbeit mit dem Kunstmuseum St. Gallen.

By Morgan Thomas.

By Morgan Thomas.