Judy Millar interview – The View from Nowhere

By Bob Chaundy for Considering Art

Published September 2019

Judy Millar’s work has seen many forms, including large paintings that tumble from the gallery ceilings in large coils. For her first solo show in London, The View from Nowhere, she presents six paintings full of energetic and colourful works that include a signature process in which she removes layers of paint from the surface after applying it. Bob Chaundry talked to Judy Millar on the first evening of her show.

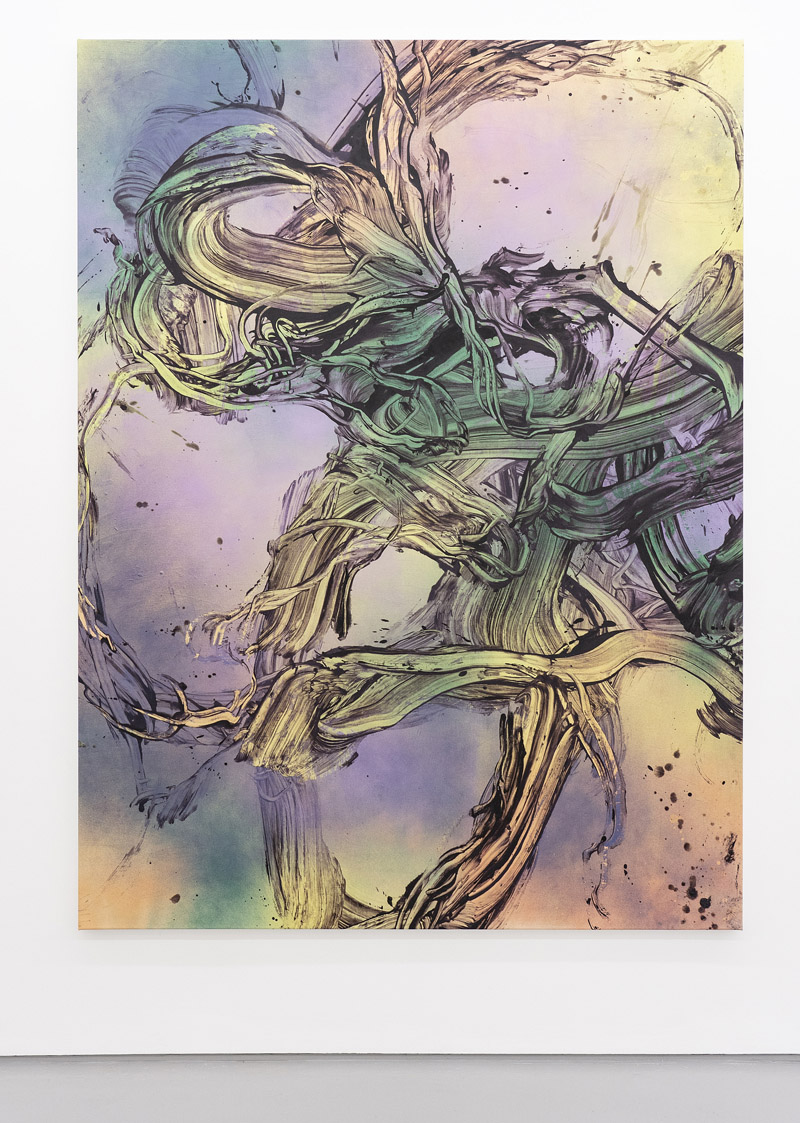

- Judy Millar ‘Without Yesterday’ 2018. Courtesy of Fold Gallery, London

How did you prepare for this show, your first solo show in London?

I work all the time and I try to choose good work that looks the right scale for the room. So I built myself a little model of the gallery and I worked with differently sized paintings that I thought would have an interesting relationship with the scale of the room.

You are quite known for your leviathan size works.

I work in a huge range of sizes, from very small to very, very large. Every work in a way has to have an interesting relationship to the body, so whether it’s a tiny scale or a big one. I think painting is like a portal and can suck a whole room into it if it’s working well. So that’s the kind of relationship I’m always looking for. I want a tension between the pictorial surface and the space it occupies.

I’ve read that you compare the act of painting to space travel.

Yes, that’s my experience when I’m working. I really feel that space and time dissolve into one another and I almost become non-existent. I suppose in contemporary terms it’s like disappearing down a black hole which is a very amazing feeling.

Is that what some would call getting into the zone?

I think athletes refer to it that way. It’s a different sort of consciousness, you step into an entirely new way of being.

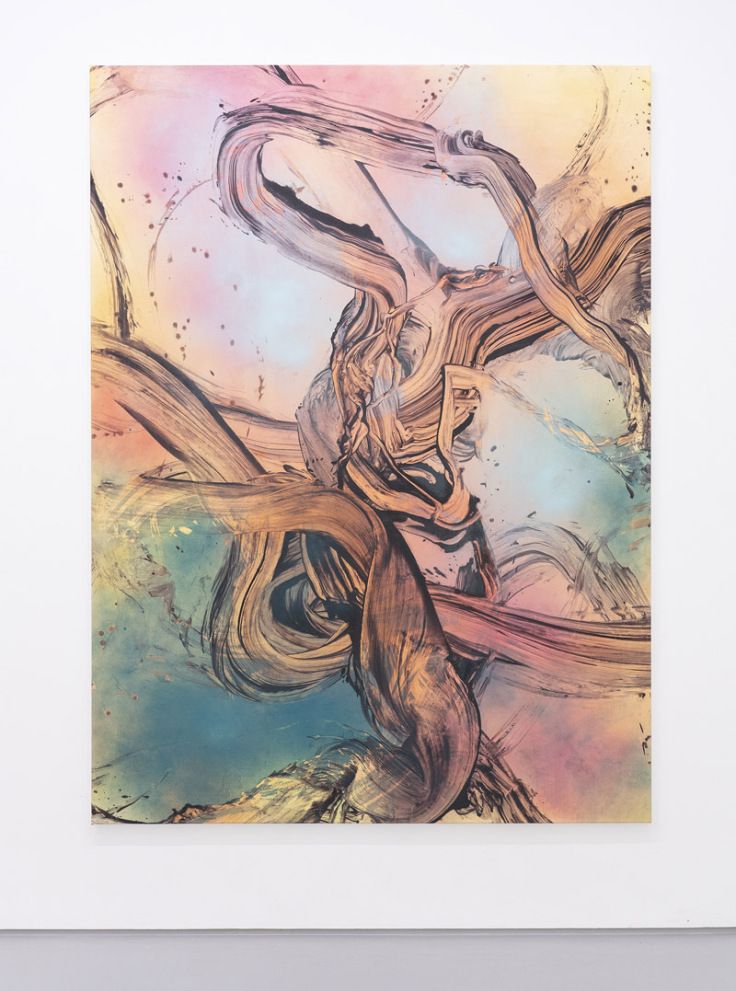

- Judy Millar, ‘Outer-space Geometry’ 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Fold Gallery, London.

My first reaction on seeing your paintings was that they’re very organic.

I think they’re both organic and highly synthetic. I’m always trying to bring the most contrary elements together in a work as possible. So, on one hand they’re very organic, on the other they’re highly artificial and synthetic. On the one hand they’re very free in their making, on the other hand they’re very constructed. I think painting at its best can bring these very paradoxical activities into one image.

Why do you feel the need to have these opposing forces together?

Because I feel that that’s what painting can do, and it’s something that very few of the other media can do and that comes from the fact that painting is both an illusion and a physical being at the same time. That’s very unique. A film is not. You can’t reach out and touch a film, it vanishes. A book is only able to be understood through a process of time. With a painting you get it all at once and you can relate to it as a physical thing while at the same time it’s highly illusionistic and a mental construct.

“I think being human, one of the dilemmas of our lives is that we live in these two realms, the mental realm and the physical realm and that causes us endless problems.”

So we have our imagination and our dreams and our fantasies and we have to deal with the reality of tables and chairs and cars and roads and all those other things. Humankind has always had to do that and I think religion attempts to bring those things together and I think art is another attempt to bring those things together to try to understand our dual existence. For me, painting can really hammer that dual existence, it can really deal with it.

So, where does your inspiration come from?

Through a long, long involvement with both looking at painting, thinking about painting and making painting and from my experiences in the visual world. And then it’s my very intimate relationship with the material I’m working with. So it’s all those things coming together.

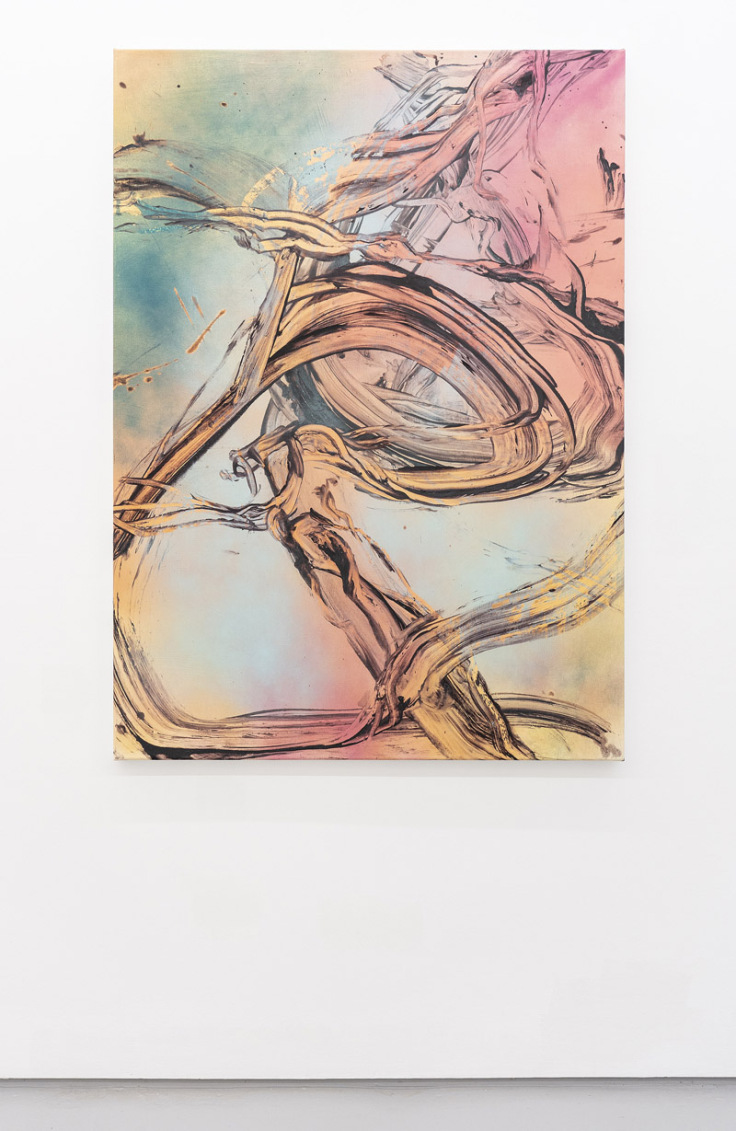

- Judy Millar, ‘Outer-space Geometry’ 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Fold Gallery, London.

Do any particular artists influence you?

Every day someone new. Every show I see, someone new. It’s extraordinary to see, as I did in the National Gallery this morning, paintings you know quite well and then you see new aspects to them.

I see colours that I think could be useful, the way artists have loosened the world up. When I look at a painting I ask myself what are they seeing. How are they trying to re-see that when they work? What have they seen, what are they seeing, and how are they presenting that are questions I’m always intrigued by.

How do you go about constructing your paintings?

It’s very traditional in many ways. I start with lighter colours and work towards darker colours. Then I’m pulling paint off the surface so it’s really a matter of putting paint on and taking it off until I arrive at something that I recognise in a way. So it’s a to-and-fro process of application and removal.

Why do you remove paint?

I started off painting in the 1980s and it was a time when deconstruction was the mode. I wanted to discover for myself what was the minimum a painting could be. So I started to remove stuff and I’ve always stayed with that. It’s a bit like a fashion designer’s work undoing clothes and finding how they could deconstruct a garment and I was trying to do the same with painting.

But do you know which bit you’re going to deconstruct before you do it?

At that time I was trying to understand how far I could deconstruct painting and I ended up with works that were just marking tape and gesso. Obviously I’ve become much more involved with image since then but there is still that aspect of putting things on and stripping it away in order to get at something that is just enough and vital.

“I saw a fantastic Francis Bacon show in Basel earlier this year and he said I want to get as close to the nervous system as possible and that really resonated with me because sometimes you want to get so close that you put your whole body in there.”

That’s when your hand will just go into the paint. You want it be as close as possible to your body. I work on the ground, it’s all very fluid. It’s quite physical, I need to use a lot of force. I walk into the works if they’re very big and paint my way out of them. I’m always finding new kinds of things to use to move the paint. I use rags and brushes and I use spray and tools that I invent and tools that I find and my fingers and feet and everything else. It’s a dirty business (laughs).

So beneath these layers of paint is a nervous system

When my hand is in the paint obviously the connection of the paint and my nervous system becomes one thing. The image becomes just the extension of the nervous system in a way.

–

Born in 1957, Judy Millar has become one of New Zealand’s best-known painters, representing her country at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009. Her work has been exhibited not only throughout her own country but also in Europe and the United States to much critical acclaim.

- Judy Millar, ‘Cloud-Rider’ 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Fold Gallery, London.

Source | More from Bob Chaundry

The View from Nowhere is showing at the Fold Gallery, 158 New Cavendish Street, London W1W 6YW until 20 October 2018.