A conversation with Judy Millar

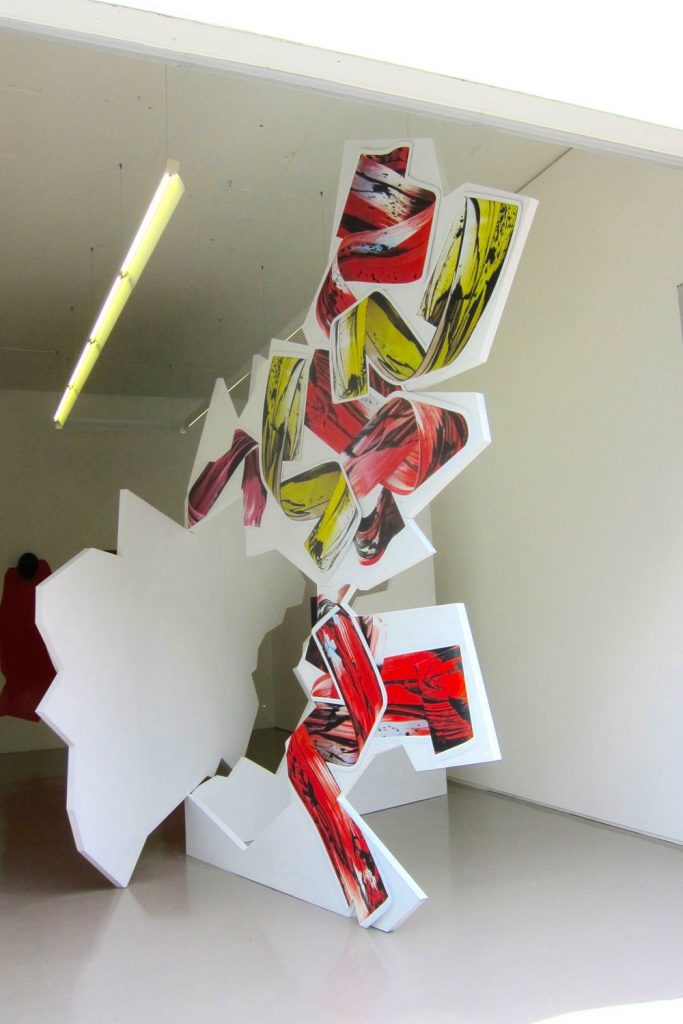

Image: Judy Millar, Advancing All Electric, 2016. Installation view, Galerie Mark Müller, Zurich. Photo: Millar Studio. Courtesy the artist.

I have heard Schwitters’ formative installation Merzbau [the alteration of rooms in his family house into sculptural environments with elaborate angled surfaces] described as a ‘walk-in collage’ of different spatial and architectural features. Does this relate in someway to your own work?

Merzbau explored new spatial ideas in art, and my work also relates to new kinds of space, specifically combining elements of architecture, sculpture and painting. I am also interested in the idea of collage that Schwitters was using. Of course, he was collaging everyday material, and I am reassembling digital reproductions of my own painted images. The worthwhile thing about showing in Europe is that you get these very new takes on the work that you are doing—connections that wouldn’t be immediately made here, in New Zealand.

Image: Judy Millar, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic and oil on paper, 89 x 64 cm (incl frame). Courtesy of Bartley + Company Art.

Do you have a name for these sculptural installation works? They still involve painterly elements—more precisely, digital reproductions of your paintings—and I am reluctant to simply refer to them as ‘sculptures’.

They are called ‘space works’. In the studio we call them ‘props’ rather than sculptures. I would always bristle when the people I work with in the studio called them ‘sculptures’. So we came to the decision that we would call them props—I quite like the word.

The space works do seem to be ‘collaged’ in the way that different spatial planes are brought together. To me, they look like massive two-dimensional jigsaw pieces that have been assembled in interesting configurations.

Yes, they are a spatial collage in this respect, so this does fit quite well with the Merzbau concerns. On the surface of the structure, I am placing images of other forms that I’ve made in three-dimensions then photographed and had printed onto sticker paper. So the main space work has images of other spatial works hanging on its surface. These images really are like big stickers on the surface of the work. Each of these stickers is stuck to a piece of thin aluminium that is then gently curved in different directions. The difference with this new work is that the stickers, instead of being flat on the surface like previous works, curl away, gently lifting away from the form itself.

So it is quite a complex piece that involves both illusionistic curves and physical curves—real shadows and images containing shadows. If anything, these works are lampooning big heavy ‘male’ sculpture. It is a very gentle dig. These are stickers! It is everything that you shouldn’t do with a traditional sculpture: it’s illusionistic, it’s not real, it’s plywood made to look like cardboard, and it carries images on its surface.

Image: Judy Millar, Advancing All Electric, 2016. Installation view, Galerie Mark Müller, Zurich. Photo: Millar Studio. Courtesy the artist.

Do you often find yourself pushing back against certain traditions or stereotypes in art, such as the prototypical painting or sculpture?

I try and undo them because I want to understand them. My way of understanding something is to pull it apart. A good sculpture is about a form in the round that both alters and is altered by the space that surrounds it. But I am more interested in it existing as an image rather than a form. This recent spatial work is primarily made up of slotted planes—it is planar in the sense that it is really just an image surface that has become a little more complicated.

Image: Judy Millar, Untitled, 2016. Acrylic and oil on paper, 115.5 x 86 cm (incl frame). Courtesy of Bartley + Company Art.

Can you talk more about this relationship between space and painting in your work? You are testing the traditional idea of sculpture by introducing the imagistic flatness of painting. But it must be noted that, while we have been speaking about your space works, you also continue to make paintings that explore the basic fluidity of paint as a medium that can be made to sit on a flat surface in different ways.

Yes, an absolutely central interest of mine is how a painting alters its spatial environment. On one level, the painted works are a ‘finding out’ process that includes some really basic stuff about how colours interact and how the very fluid and incredible medium of paint functions. But I am painting these works flat on the floor and when I am doing this, I am trying to build an entire space. It is not that I am just thinking of a two-dimensional planar surface on the ground. It is as though I am trying to build a dome-like space above the canvas. I am in space; my movements are in space. So the painting is really about creating a form of space. It almost lands on that plane with the hope that, when I put the canvas upright, it is going to then come into the viewer’s space—that it is going to determine this space or influence it in someway.

While Schwitters might be a useful reference for your space works, I am venturing that some viewers might also think of Abstract Expressionism and Action Painting with respect to the gestural element involved in your paintings. Do you have any thoughts about this?

The word that always sets my teeth on edge is ‘gesture.’ Gesture seems like something that comes gushing out from deep inside you. That is not really what I am interested in. My work is much more about drawing; it is about looking and seeing, less about ‘expressing’. I’m using gesture only in the sense that a gesture can communicate something.

But Abstract Expressionism did produce some pretty amazing work and it also fell into a very big hole. I think there is something in there that is still worth exploring—that is still worth bringing forward. But like everything that is continually repeated, Action Painting became nothing but a mannerism. And I am very aware that I am referencing this form of painting in a ‘gone’ way. I am not really parodying it; rather I am referencing a ‘gone form’. It is a form that already stands for something. This continues to interest me greatly with painting. — Read original article here.