www.roberthealdgallery.com , presents Untitled 2005, opening September 26th

Robert Heald Gallery Wellington, New Zealand presents Paintovers – Opening 12 March 2020

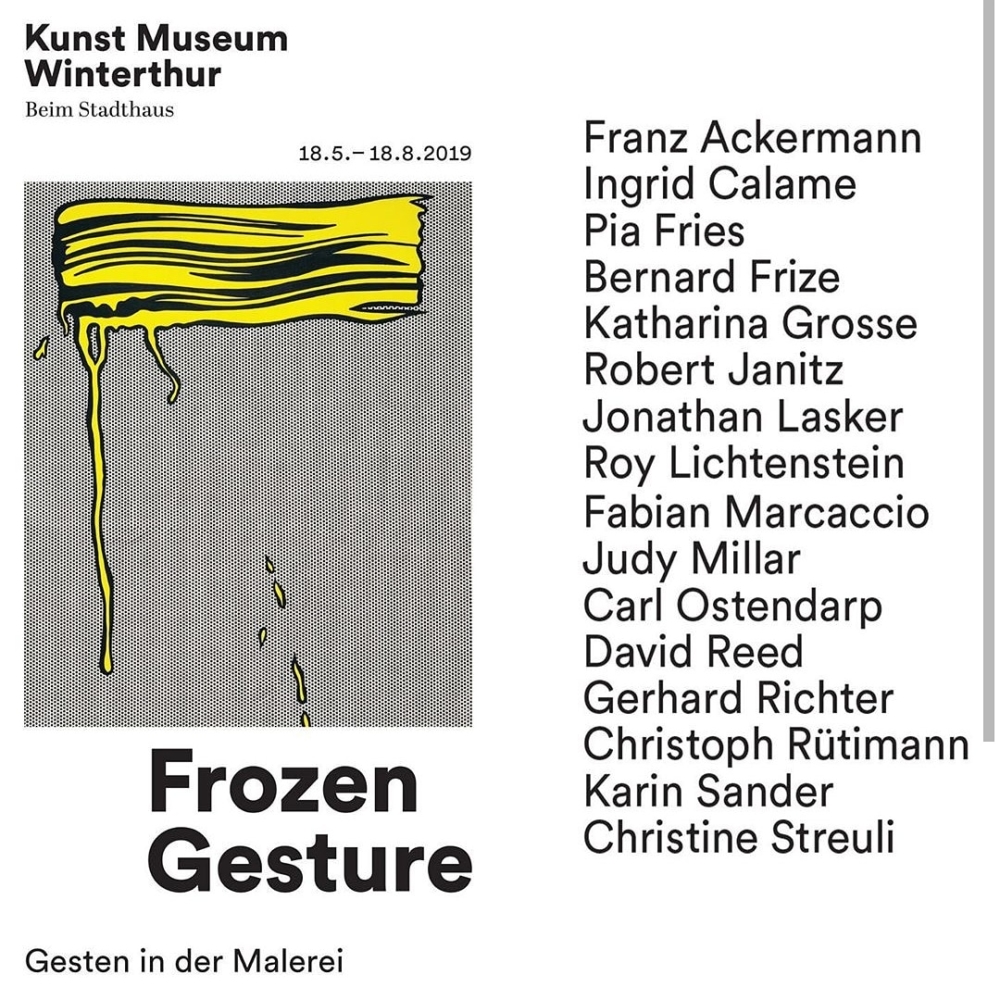

Frozen Gesture Kunst Museum Winterthur, Switzerland. 18th May – 18th August 2018

Galerie Mark Mueller, Zurich presents the group exhibition Single, but happy. 8th June – 20th July

Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand presents A World Not Of Things, a solo exhibition of new paintings by Judy Millar. 17th April – 4th May 2019

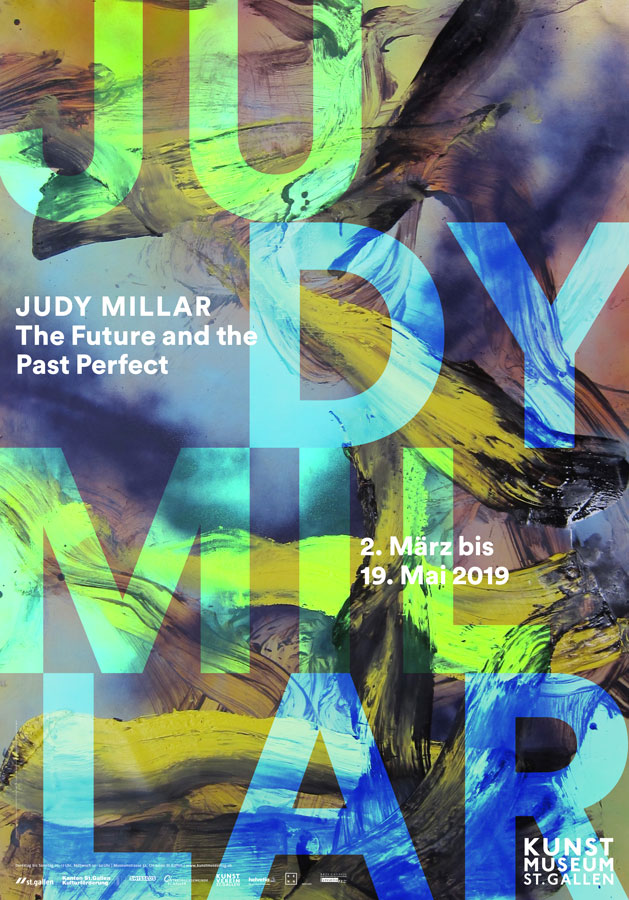

The Future and the Past Perfect – a survey of Millar’s work from 1981 to 2018. Kunstmuseum St Gallen, Switzerland. 2nd March – 19th May 2019.

Art Collector Australia interviews Judy Millar about her work in 2019’s Art Basel. Specifically in connection to the late New Zealand painter Colin McCahon’s legacy and his practice in relation to his International contemporaries.

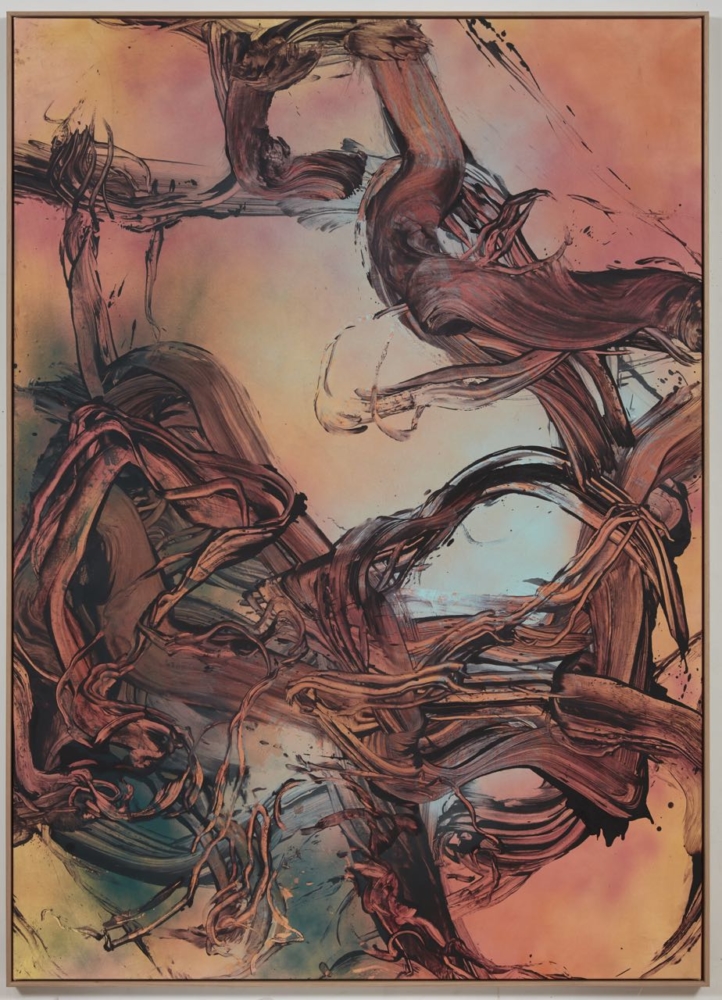

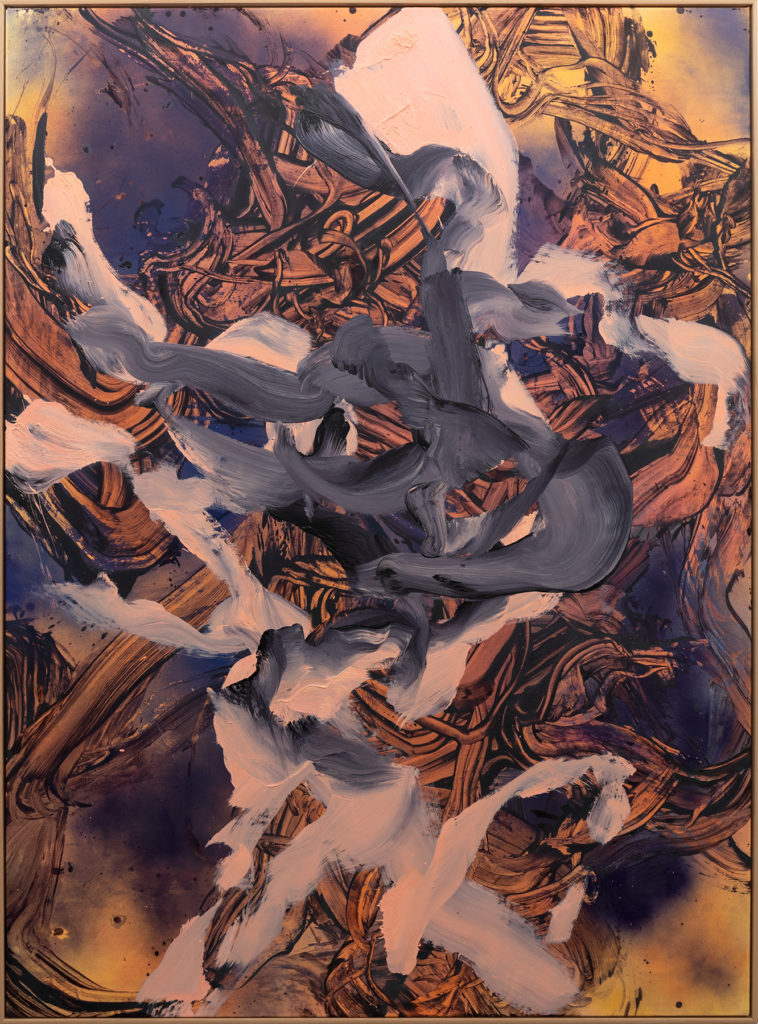

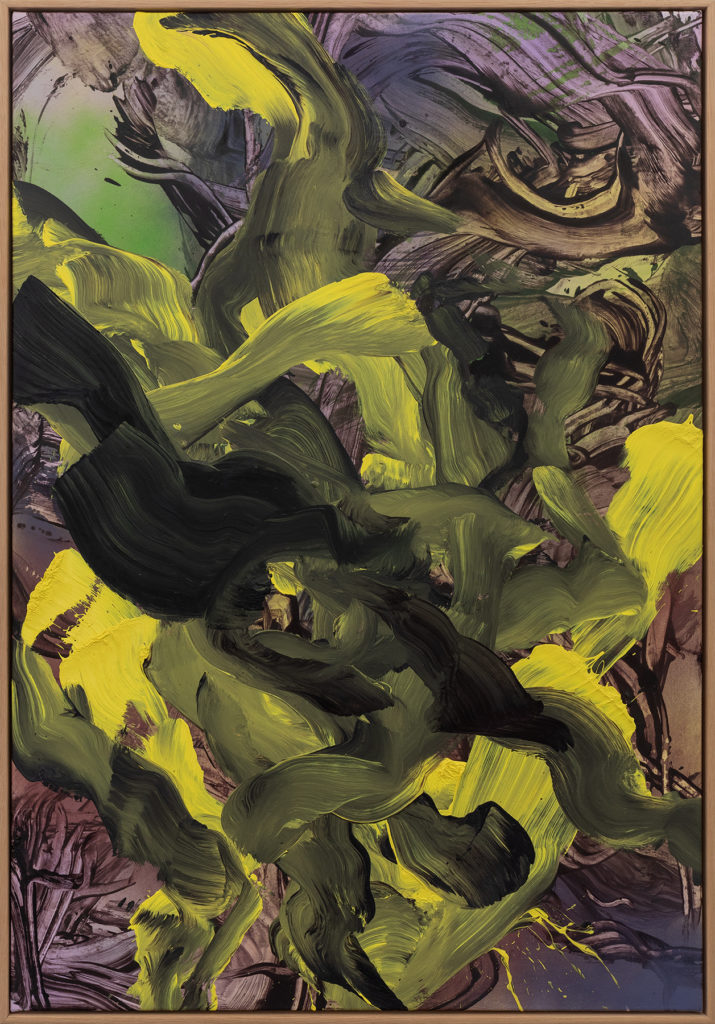

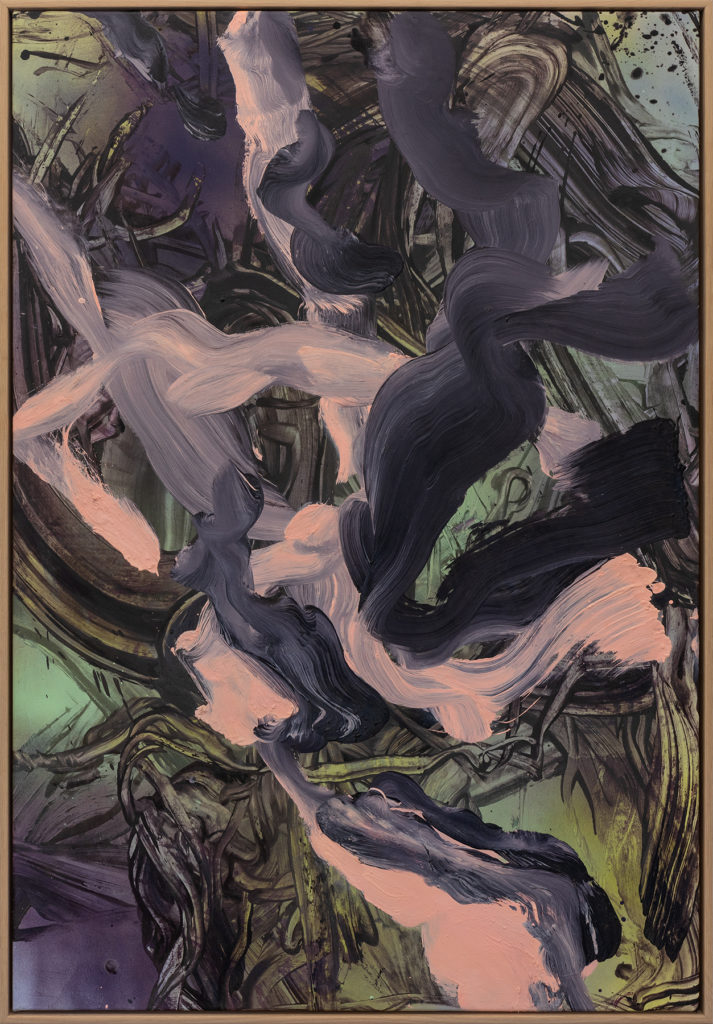

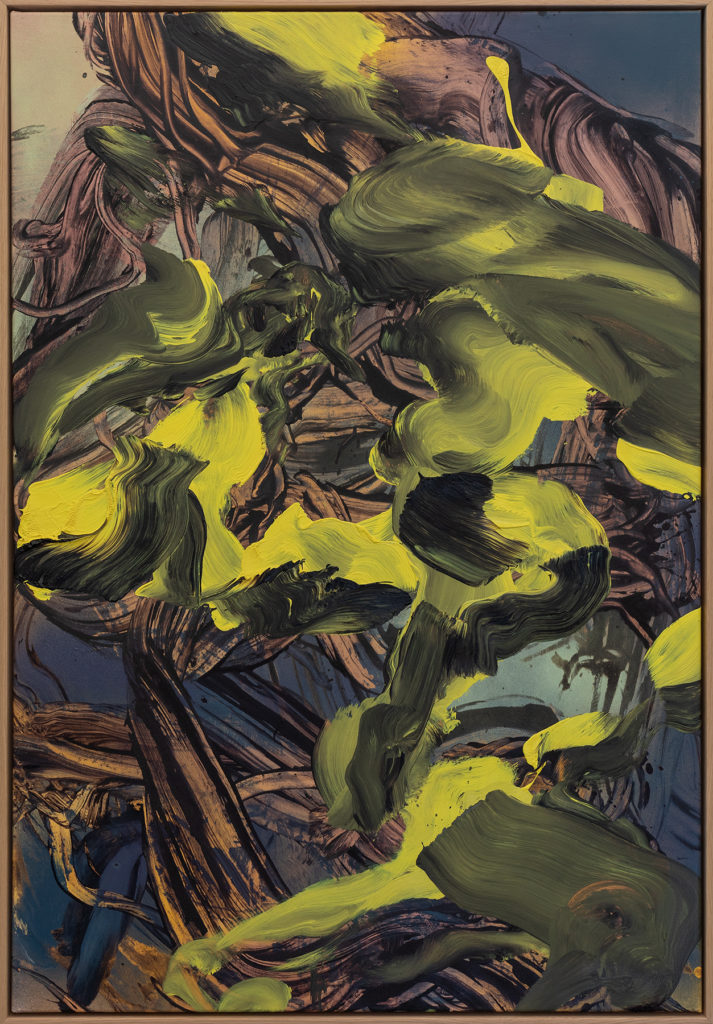

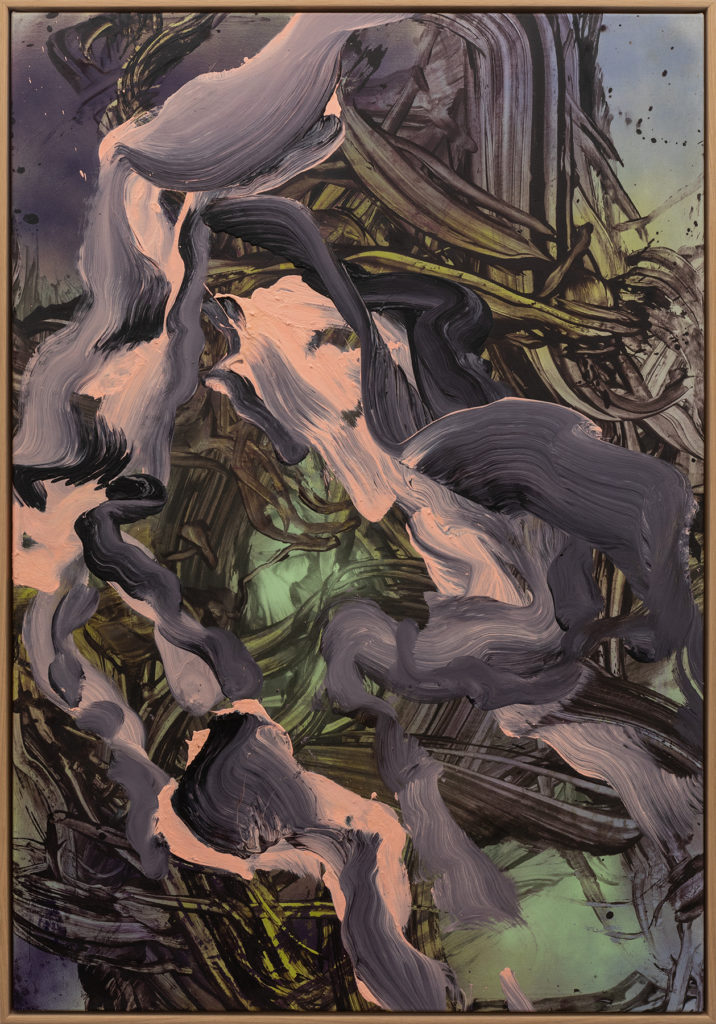

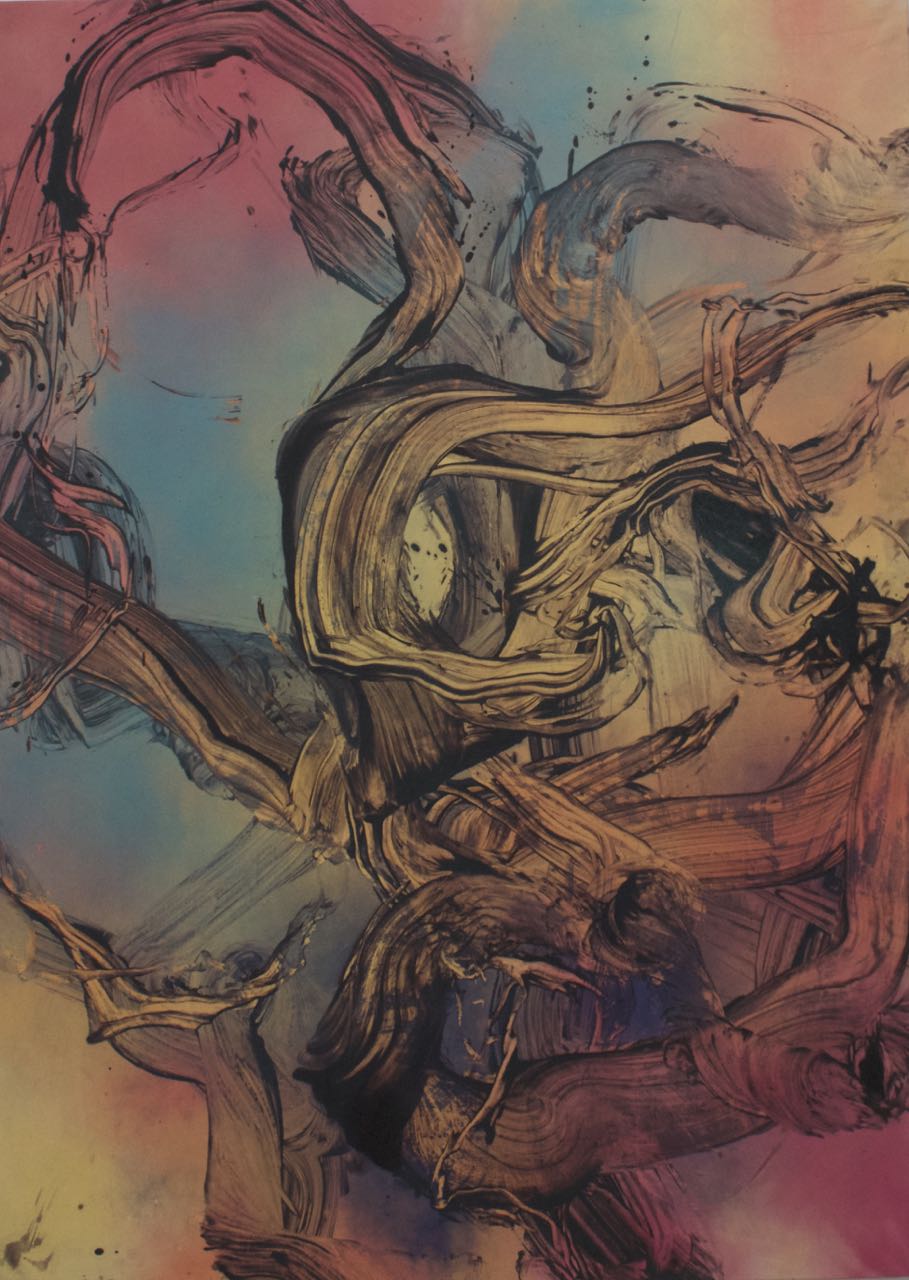

In this new group of works form becomes the graph of activity. The appearance of “things” emerge from the web of painted lines and fields of colour. These things – hard to name but fleetingly apparent, establish a semi-believable pictorial space. These strangely spatial paintings exude an otherworldly luminosity as if emitting light from a distant time and place.

http://www.roberthealdgallery.com, Wellington, New Zealand. Opening 12 March 2020

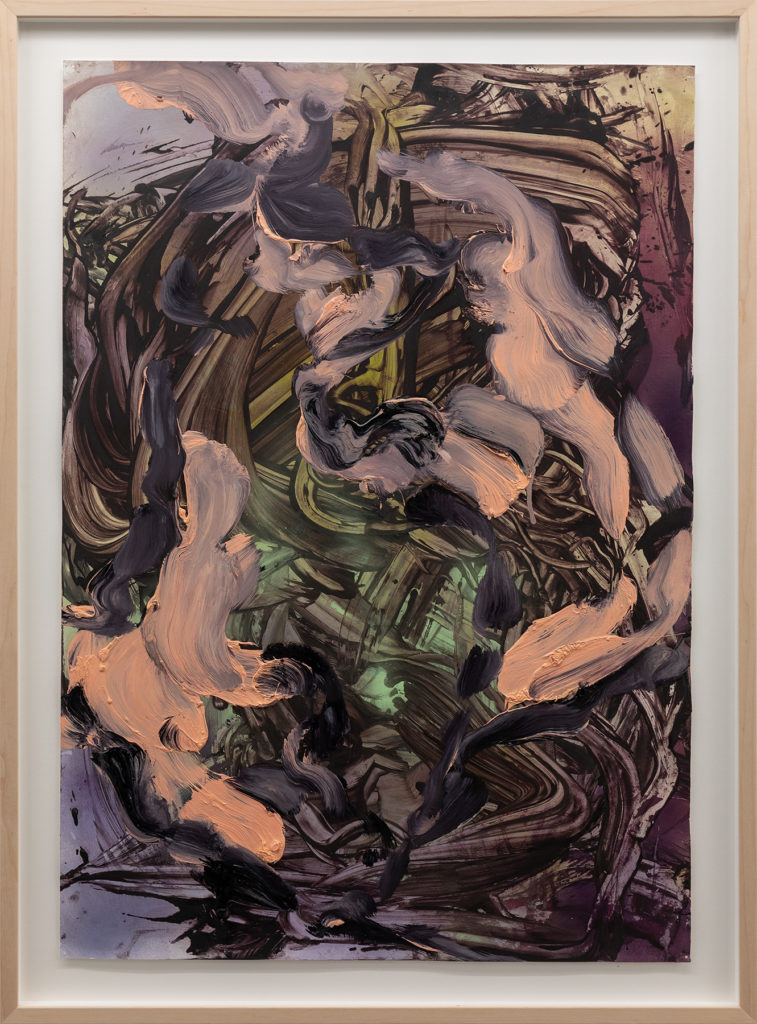

“Untitled, 2005, is both an extraordinary painting in its own right and a key pivotal work in Millar’s œuvre. Alternatively celestial or oceanic, it marks a critical juncture in her practice coincident with the consolidation of her on-going commitment to presence in both Aotearoa New Zealand and Germany and Europe. While pronounced now, this wasn’t necessarily quite so marked when it was first shown in an expansive and experimental exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery “I will, can, must, may, would like to express”from September to November that year. It was the most difficult painting in the exhibition, a building site painting or work in construction as Millar described it in an accompanying exhibition brochure. Certainly unruly, anarchic, even within an exhibition that challenged assumptions as to what painting might entail, it escalated the core motivations of her practice at that time. In an exhibition filled with actual and potential jumping off points, this painting was the most extreme, the most risk-taking and, in a very precise sense given it is such an important concern for the artist, in retrospect it seems to have been the most present.”

P. Shand 2019

18th May – 18th August 2019

In 1965 Roy Lichtenstein created his famous brushstrokes and in so doing transformed the subjective gesture of heroic Modernism into a trivial comic drawing, transposed into the large format of a museum.

Konrad Bitterli, Lynn Kost, and Andrea Lutz curate the extensive Frozen Gesture exhibition – a sheer range of gestures in contemporary painting, presented by Kunst Museum Winterthur. The exhibition brings together important individual pieces by outstanding protagonists of Abstract Art, such as Gerhard Richter and David Reed, with extensive work groups of contemporary artists such as Franz Ackermann, Pia Fries and Judy Millar – to create a fascinating display of works of exceptional painterly quality and inconceivable sensory appeal.

The spontaneous movement of the brush on canvas mutated into a quote, the emotional exploration of depth morphed into a Pop surface in signal colors. The purported immediacy of the expressive painterly act thus became an ironic reflection on the medium of painting using the means of mass culture.

This distanced and self-reflective approach had defined contemporary painting since the end of Modernism. It highlighted the fundamental elements of the image, such as the appearance of the colors and the pigment, the color fields and their limits, and not least the application of paint in the form of a gesture.

This gesture had long since abandoned directly expressing existence in favor of any number of different discursive strategies and painterly approaches. To this day, artists underscore the problematic nature of the impact of the application of color and are forever reinterpreting it – from the gesture as a semiotic abbreviation for painting through to its diverse transformations in images.

Curators: Konrad Bitterli, Lynn Kost, and Andrea Lutz

Galerie Mark Mueller presents the group exhibition Single, but happy. Zurich, 8th June – 20th July 2019

17th April – 11 May 2019

Judy Millar, March 2019

I was sitting down to write up notes about this exhibition on March 15th when headlines wrote themselves across my screen. A man and a gun had vented rage and hate against fellow New Zealanders in their time of prayer.

Times like this make you question a life in art, a life that is in itself a kind of devotion. It can seem to lack the necessary force to counter-strike. It can seem too invisible as an influence on everyday life.

The seeming inadequacies of art became even starker when I began to view this desperate act of violence as part of a broader picture appearing around the world. We have long lived in a world that has assumed white superiority but it is fast ramping up, in so many parts of the world, into an outright declaration of supremacy.

We are living in a time where democracy itself seems challenged if not directly threatened. We have reached a point where we make enemies of those who hold different political perspectives than our own. We live in a time where we ‘unfriend’ those who challenge or criticise us. Where we object to listening to opinions we don’t already fully agree with and where we respond with outrage to views that clash with our own. All of these attitudes and behaviours run counter to the core democratic principle of respect for differing opinions.

I have always believed that involvement in art is primarily about absorbing different points of view. Being open to art is about gaining the flexibility to look at things from all sides and in doing so to nourish our empathic humanity. But on March 15th I once again had to ask – is this enough?

I still don’t have an answer to that question but while thinking deeply on this over the ensuing days I stumbled on this quote from Simone Weill. In her Notebooks she writes that we are helped by meditating on “absurdities which project light”.

For now this definition seems a suitable definition for art, and one that can give me some hope as to art’s ongoing importance. At the very least I will take it as a definition of my own project.

I have worked hard to light these canvasses from the inside out. I have sought to combine the paradoxes of coloured earth and a suggestion of the immaterial. I have desired a feeling of space and surface coexisting. I have tried to evoke dusk – the time of day that is neither day nor night but is both at the same time. I have wanted to suggest a multitude of things and nothing at all.

I know this is not enough, but for the interim it is what I can offer. I hope that it will encourage contrasting viewpoints. In doing so it might enable the widening of our individual perspectives.

REVIEW

Judy Millar arbeitet sich an der Malerei ab, zerlegt die Geschichte und die Techniken des Mediums. Damit wurde sie zur wohl bekanntesten Künstlerin Neuseelands. Das Kunstmuseum St. Gallen widmet ihr nun die erste große Einzelausstellung außerhalb ihres Heimatlandes.

Judy Millar, Don’t Call Me Baby, Baby, 2002, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Nach eigener Aussage geht es Judy Millar darum, ihren Platz in einem Genre zu finden, das für sie in ihrer persönlichen und künstlerischen Entwicklung keine Vorbilder bereithielt. Der Blick zurück in die Kunstgeschichte der Malerei war für sie primär europäisch und männlich geprägt. Als neuseeländische weibliche Künstlerin hinterfragt sie diesen Kanon distanziert, dekonstruiert ihn bis ins Detail und entwickelt dadurch einen eigenen unverwechselbaren Stil.

Judy Millar, Untitled 2005, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Dies zeigt sich bereits an der für sie typischen und sehr individuellen Arbeitsweise, die durch einen Prozess des Wegnehmens geprägt ist. Damit kehrt sie das grundlegende Prinzip der Malerei um: Aus dem additiven Auftragen von Farbe und Material wird ein nicht minder ausdrucksstarker Vorgang der Substraktion. Auf den ersten Blick erinnert der Duktus der Gemälde an intuitiv und dynamisch aufgetragene Pinselstriche. Tatsächlich trägt die Künstlerin Schichten von Ölfarbe auf die Leinwand auf und nimmt diese mit Stoffbahnen oder mit Sand gefüllten Plastiksäcken wieder von der Oberfläche ab. Dies sei − ganz anders als der erste Eindruck vermuten lässt − ein sehr langsamer und kompositorischer Vorgang körperlicher Anstrengung, erklärt Judy Millar. Und tatsächlich sind die in den Werken manifestierte physische Präsenz und der gestische Ausdruck unmittelbar für den Betrachter spürbar.

Millar pendelt zwischen Auckland und Berlin und identifiziert sich mit der aus der räumlichen und charakterbezogenen Distanz entstehenden Ambivalenz der beiden Orte. Zwischen der großflächigen Landschaft Neuseelands und dem dazu in Kontrast stehenden Leben in der Großstadt bildet sie ihre künstlerische Identität und zieht ihre Inspiration für neue Arbeiten. Die großformatig angelegten, raumgreifenden und extra anlässlich der Ausstellung „The Future and the Past Perfect“ in der Kunsthalle St. Gallen konzipierten Arbeiten „It to Them, to Us to I“ konnten somit nur im Kontext der neuseeländischen Weite entstehen.

Judy Millar, It to Them, to Us to I, 2018, Foto: Sebastian Stadler

Dabei interessiert die Künstlerin auch das Spannungsverhältnis zwischen Malerei und Architektur. Die Werke sind bewusst überdimensional gestaltet und scheinen die mit Stuckelementen und Bordüren geschmückten Räume des Museums regelrecht zu sprengen. Gleichzeitig geht es Judy Millar dabei aber nicht um eine skulpturale Ebene von Malerei. Sie sieht ihre Arbeiten explizit als Gemälde an und will sie nicht als genreübergreifende Objekte verstanden wissen. Die Kunsterfahrung soll sich deshalb auf die frontale Betrachtung der eindimensionalen Leinwände beschränken. Ein allseitiges Begehen des Raumes, um einen Blick auf die Rückseite der Werke zu werfen, ist gerade nicht intendiert.

Bei Judy Millar geht es in vielerlei Hinsicht zunächst um die Herstellung von Referenzen durch Nachahmung, welche durch eine eigenständige Interpretation aufgebrochen werden. Besonders deutlich wird diese Herangehensweise an Millars Auseinandersetzung mit der Kunstgeschichte der Malerei. Es zeigt sich an der Optik perfekt durchgeführter Pinselstriche, die gar keine sind. Vor allem die jüngeren Werkserien scheinen besonders impulsiv kreiert, beruhen jedoch wie alle Arbeiten der Künstlerin auf einer bewussten Farbauswahl und Durchführung der einzelnen Arbeitsschritte. So wird der Betrachter immer wieder dazu veranlasst, seine eigene Wahrnehmung zu hinterfragen und einen neuen Zugang zur Malerei zu finden.

WANN: Die Einzelausstellung der Künstlerin mit dem Titel „The Future and the Past Perfect“ ist noch bis zum 19. Mai zu sehen.

WO: Im Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, Museumstrasse 32 in 9000 St.Gallen.

Diese Review entstand in freundlicher Zusammenarbeit mit dem Kunstmuseum St. Gallen.

2nd March – 19th May 2019

The Kunstmuseum St Gallen is offering an overview of Millar’s entire oeuvre, which she has created in Auckland and partly in Berlin over the past forty years. Together with her well-known serial paintings with expressive brushwork and broken up spaces, the artist has created a spatial installation of paintings for the Skylight Hall. A surprise is the early abstract geometric drawings from the 1980s shown for the first time in Europe.

Curator: Roland Waespe

More information.

For Art Basel Hong Kong 2019, Gow Langsford Gallery presents a selection of work that demonstrates the late New Zealand painter Colin McCahon’s legacy and considers his practice in relation to his International contemporaries.

Can you tell me what you’ve been working on for the show?

I am showing new paintings, not exactly made with this show in mind but certainly indebted to McCahon. His oeuvre is so vast and rich that any painter working in New Zealand will find themselves conscious of his presence over and over again.

I recently finished reading Knausgard’s A Time for Everything in which he retells biblical stories, setting them in his homeland. I live on the Tasman seacoast not far from where McCahon painted most of his late works centred on religious texts. The mix of bible story, angels, Noah, coastlines, gannets and rising waters seems to have filled my imagination this summer.

“The telling of great stories set in your own backyard has lead me to seriously reconsider the importance of place. My own works have become increasingly infused with West Coast Auckland. The landscape is always there.”

How would you describe McCahon’s legacy within New Zealand art history?

McCahon was a visionary. He brought an ambition to his work that sought to match the great painters of history. Through his commitment, he laid the ground for art to become a serious undertaking in Aotearoa [New Zealand]. For it to matter, because it spoke directly to an experience of the country as it was. It was as if he banged a stake in the ground and stood by it.

You were the first artist to take up the McCahon House Artist in Residence programme in 2006, which saw you move into a purpose-built studio just next door to the bach [a New Zealand term for holiday house] where McCahon and his family lived in the 1950s. What did you take from this experience?

This time was a complete turning point for me. The bach where the McCahon family lived has been turned into a small museum containing his archived correspondence and tapes of him talking about various things. As a resident you get 24-hour access to the museum. I would go very often at night and sit and listen to Colin speaking. It was as if he was talking directly to me. Telling me to wise up, get serious. It came at the perfect time in my life. In that house you know that art matters.

How does the idea of legacy – of leaving something behind you that has the potential to influence future generations – play into your practice? Has this changed over time?

I’m an art history junky and love to see how things have influenced and do influence other things. But I have the feeling we are in a new world. Everything is on the table now and the pathways of influence will become largely untraceable in the future I think.

What would you say is the most important issue facing New Zealand artists working today?

I think the biggest issue is, as for everyone else, is sustainability. Artists working in New Zealand need to travel a lot and that’s going to be increasingly difficult to justify.

We are also suffering in New Zealand from an absence of genuine critique. Increasingly we are divided into smaller and smaller interest groups that make rigorous expansive discussion impossible; this is making it very difficult to develop complex artistic practices.

13th Sept – 20th Oct 2018

The colour palate is double-edged; reminding us of the moments when nature thrills us with sunsets, sunrises and deep blue lagoons but also recalling the colours of comic books and their depictions of outer space adventure and future doom. Millar, a fan of popular science, describes the activity of painting as a form of space travel.

“I used to think painting was a way of thinking. Now I know it to be much more than that. It is the flash of big-brain meeting small-brain, of consciousness meeting thought or of consciousness meeting mind through the body. Of outer space and inner space colliding.”

In this new group of works form becomes the graph of activity. The appearance of “things” emerges from the web of painted lines and fields of colour. Things hard to name but fleetingly apparent establish a semi-believable pictorial space. These strangely spatial paintings exude an otherworldly luminosity as if emitting light from a distant time and place.

As Millar applies then removes layers of paint from the surface of the works she seems to release energy as if an image has been held in matter and is now freed into visibility.

“The first ‘coast works’ in their primary saturations have remained unseen by anyone else since the late 1980s. They have been harshly edited over the years with many being burnt. Those remaining seem now to be a nucleus of thoughts and responses that have emerged decades later.”